Moga: Over 2,000 men covered in blankets squat, stand, and crowd around a turf, watching a circle-style kabaddi match in Punjab’s Moga district. Brand new tractors, which the winners will take home, are parked adjacent to the ground. Fourteen bare-chested players in Adidas shorts raid through the biting cold whispering “kabaddi-kabaddi”. But it is not the scorers who have the biggest responsibility of ensuring the game goes uninterrupted. The players are being closely watched over by policemen. They know kabaddi is no longer just a humble rural sport here—it is the newest turf where gangs of Punjab settle their scores with bloodshed.

The 16 December killing of kabaddi player and promoter Kanwar Digvijay Singh alias Rana Balachauria is the latest in a spate of murders dotting Punjab’s kabaddi-verse. It was the fourth murder linked to the kabaddi world in less than a year. Balachauria’s killers came to him with a selfie request and shot him point blank in police presence. There was panic among the 1,000 spectators present. The shooters were making a statement.

“The player, organiser, or promoter becomes the face, and that’s who they hit to send a message. This is what happened with Balachauria, Tejpal and Gurvinder,” a senior police officer told ThePrint. Kabaddi players Tejpal Singh and Gurvinder Singh were shot dead in Ludhiana’s Jagraon area in October 2025.

Moga is the backyard of Davinder Bambiha—the slain gangster who first earned praise with his game and then instilled fear with his criminal acts. Police have traced the recent killings to the Bambiha gang.

“Players, coaches, organisers, and the public. Everybody is scared. After what happened in Mohali or Ludhiana, people don’t want to take chances. Usually there are 10,000 people here. This time, barely 2,000 people showed up. Nobody will stay post sunset,” said Kuldeep Singh Sangha, sarpanch of Daroli Bhai village in district Moga where the kabaddi tournament has been organised for over 50 years now.

What is unfolding on Punjab’s kabaddi turfs is part of a larger shift in the state’s crime landscape. As the gang networks face increased pressure from police, investigators said, illicit money is being routed through hawala and betting apps. Extortion money too is entering the sport. The gangs penetrated kabaddi as the state governments largely pulled out of the sport, creating a vacuum that is now turning bloody. Punjab once projected kabaddi on the global stage. It was invested in World Cups and professional leagues. Today, players speak less about medals and worry more for their lives.

“What once unfolded as village competition is now shaped by prize money, visibility, and rival power networks, turning kabaddi grounds into gang war turfs. And, everybody wants a piece of the cake,” said Gurmeet Singh Chauhan, DIG, Anti-Gangster Task Force.

Also read: A Padma Shri & a visit by PM Modi: What’s behind BJP’s Dera Ballan outreach in Punjab

Kabaddi’s kick and kill

The Kabaddi killings stretch back to March 2022, when one of Punjab’s top kabaddi players, Sandeep Nangal Ambian, was gunned down mid-match in Jalandhar’s Mallian Khurd Village. Police said the murder stemmed from rivalry between kabaddi associations competing for control over national and international leagues. Back then, it was Davinder Bambiha’s gang that had claimed responsibility for the killing.

But the murders didn’t stop.

In November 2024, Sukhwinder Singh was shot dead in Tarn Taran by the Lawrence Bishnoi gang. Tejpal Singh was shot dead in Jagraon in October 2025—police said it was a long-standing personal rivalry. And just a month before Balachauria’s killing, Gurvinder Singh, another kabaddi player was shot dead, with Lawrence Bishnoi gang claiming responsibility. A Facebook post purportedly from gang members said the killing was “a warning for whoever sides with our enemies.”

And now, Balachauria in Mohali. Most killings have centred around shifting alliances, sponsorship disputes, and dominance over tournaments. A promoter or player perceived to be backed by one gang becomes a target of the rival group. As money, territory, and visibility shift, so do these alignments, sometimes within months.

What connects these cases is not just personal enmity but the collapse of an organised structure. Senior police officers ThePrint spoke with pointed to the period after the 2017 change of government, when the Congress administration discontinued state-backed kabaddi events, particularly the World Kabaddi Cup.”

“There was never a perfect system,” a senior Punjab Police officer said, “but there was at least a structure. When that disappeared, kabaddi became free for all.”

Many players who once competed under organised banners such the World Kabaddi Cup and Punjab Kabaddi Association affiliated leagues began playing independent tournaments in Punjab and abroad, particularly in Canada and Australia. Clubs formed leagues in the UK, Canada, Italy, often operating without a single governing authority.

The SAD-BJP government before 2014, particularly under Deputy CM Sukhbir Singh Badal, promoted circle-style kabaddi as the ‘Maa Kheda of Punjab’ to build a sports culture, combat drug addiction among rural youth, and gain political mileage.

The Kabaddi World Cup, which began around 2010, offered huge cash prizes and provided stadium infrastructure. With it, came job security for players, former Deputy Chief Minister of Punjab Sukhbir Singh Badal told ThePrint.

With the Congress government coming to power, the World Kabaddi Cup was discontinued. Former sports minister Rana Gurmeet Singh Sodhi had called the world cup Akalis’ personal event. The vacuum left by the government allowed multiple private, often non-affiliated, federations to emerge, driven by personal or political interests. This invited NRI funding, with tournaments often operating in a legal gray area.

Now, the AAP government is trying to reclaim the space with its ‘Khedan Watan Punjab Diyan’ initiative, aimed at promoting rural sports and combating drug menace. The government’s renewed focus has seen a slow shift from circle style kabaddi to national/standard format, said Harpreet Singh Sudan, Director of Sports Department, Government of Punjab.

Also read: Indian video games finally bring mythology into storyline. Taking it to AAA level

When visibility became the currency

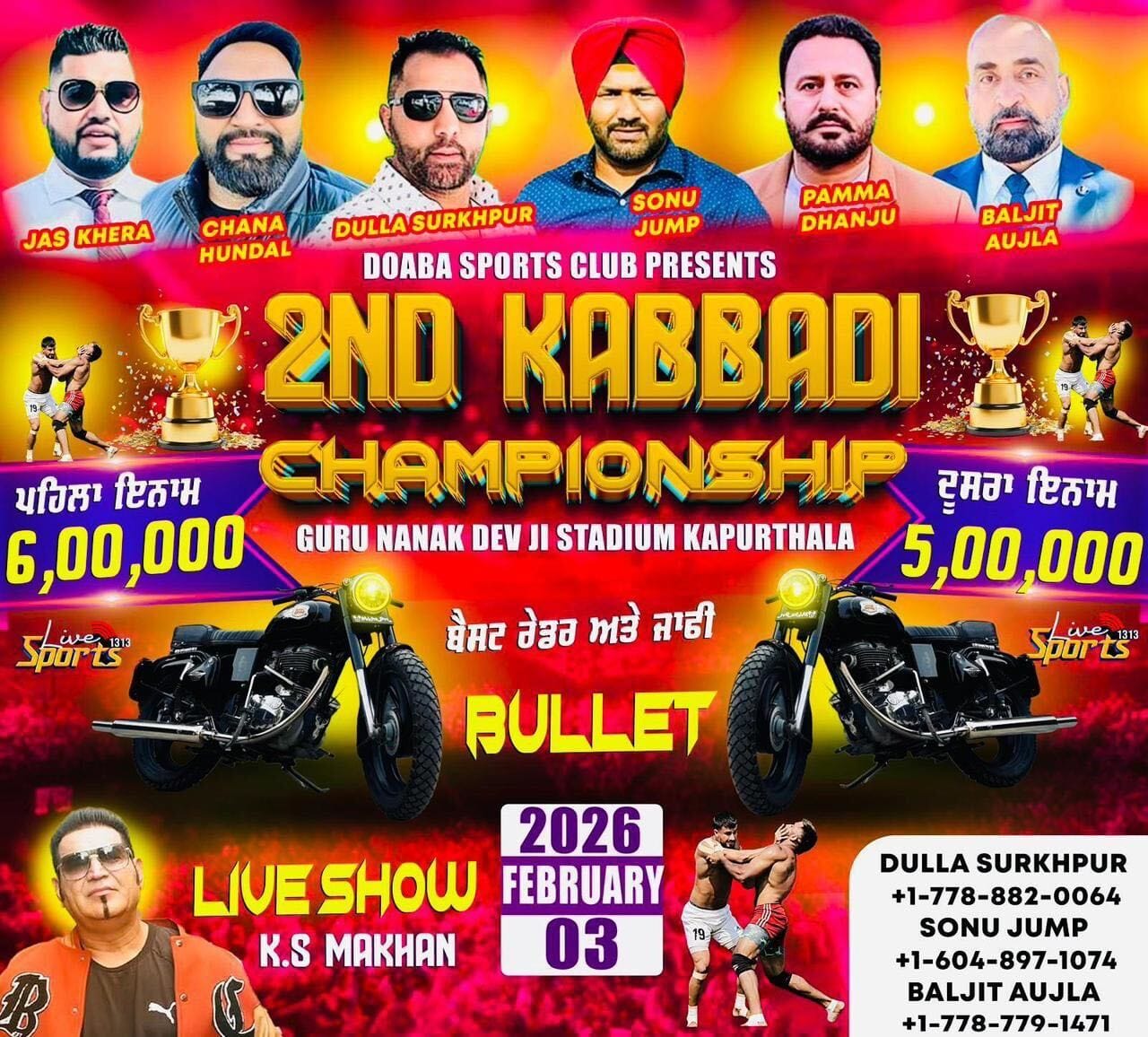

Jas Khera, a resident of Canada, has been organising kabaddi tournaments in the US, Canada, and Punjab for decades. According to him, Kabaddi has turned into a sport of ego and players want big money, bigger prizes. And organisers will do anything to cater to the demands.

Now, to organise a district level kabaddi match, it costs around Rs. 1.5 crore, while a ‘pind’ level kabaddi match is organised for Rs. 25-35 lakh. “We have to pay somewhere around Rs 15,000-20,000 for each player depending on their popularity,” he said.

Then comes the prize money. The winner gets Rs six lakh while the runners up secure Rs five lakh.

With time, Khera said, cultural programs became key to drawing crowds to the ‘mitti’ grounds. “We had Babbu Mann perform at our ground. This year, KS Mann will perform. Singers have fan following, there are crowds that get drawn. This is why sponsorships come in,” he said.

The visibility became currency for gangs, said the officer quoted above. Big city tournaments in Mohali, Kharar, and Jalandhar attracted advertisers.

“If you control the tournament, you control who is invited, whose name is announced, whose posters go up,” said Chauhan.

Be it gangs of Jagjit Singh alias Jaggi of Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) terror module, Lawrence Bishnoi, who started with student politics, or Davinder Bambiha — they all recognised kabaddi as a low-risk, high reward arena: large crowds, cash transactions, and minimal oversight.

“The promoters were either pressured to pay for protection, or asked to align with particular groups. Those who resisted, or openly backed rival networks, became targets,” said the officer. Sandeep Nangal Ambian’s death is one such example.

Snover Dhillon, a Brampton-based kabaddi player, was involved in the murder of Sandeep over “professional rivalry.”

According to the police, he had tried to convince many players to join The National Kabaddi Federation of Ontario, which was a prominent group organising kabaddi events in Ontario. At the time, most of the big players were associated with Major League Kabaddi, which was prominent in both north India and in NRI circuit, and it was being managed by Sandeep, rendering Dhillon’s federation struggle for quality players. This fueled the rivalry.

Kabaddi’s entanglement with celebrity culture only increased the stakes—through NRI-funded tournaments, YouTube livestreams, and celebrity performances at matches. This escalation of gang wars across Punjab is no longer confined to traditional rackets such as drug trafficking, arms smuggling, land and real estate extortion and contract killing. It is actively seeking control over high visibility spaces of kabaddi and music—mirroring patterns to Mumbai’s underworld in the 1990s and 2000s.

The A-listers of the Punjabi music industry have all received ransom calls, including B Praak, AP Dhillon, Dilnoor, Gippy Grewal, among others.

The overlap is deliberate, police said. Gangsters leverage cultural influence through music, while using kabaddi tournaments to assert territorial dominance, to launder money, and to extract protection payments.

Live performances have been central to kabaddi. In the past, tiff between the popularity of Punjabi singers Babbu Mann and Siddhu Moosewala, too has been a reason of contention for gangs. At one of the kabaddi tournaments, where Babbu Mann has always performed, a new face, Moosewala’s, became a flashpoint in 2020.

Even in the BBC documentary The Killing Call, gangster Goldy Brar revealed the first dispute with Siddhu Moosewala began when he returned to India. The trigger was when Moosewala promoted a kabaddi tournament in a village, linked to Brar’s rival Bambiha gang.

Also read: How Skill India lost its way by creating a parallel NGO universe of frauds

A turf for all

For decades, kabaddi in Punjab moved at the pace of village life. It was played in open fields, in organised melas, and sustained by families who believed in the sport.

Sandeep Sandhu, whose father Labh Singh Sandhu, a sports journalist, documented Punjab’s sports for years, grew up listening to the stories of that era.

“Kabaddi wasn’t about profit then. It was about pride. Families would spend their own money to keep the tournament going. There were no advertisers then.”

Back in the 1990s, it was the Purewal brothers who organised Purewal Games in Hakimpur Doaba region of Punjab. The annual mela, often called the ‘Olympics of Doaba,’ featured kabaddi, wrestling, and athletics, and it drew players from across Punjab, said Sandhu.

“The Purewals brought in NRI money from Canada and the US. With money came support, and players. As the new generation slowly took over, the spending increased, and kabaddi began to change,” he said.

The first big shift came with migration. By the late 1990s, Punjabi kabaddi players were taken to Canada, where the sport found a devoted NRI audience. Money began flowing back into the village tournaments.

“When people saw the kind of cash, kabaddi became a big sport,” Sandhu said. “Everyone wanted to either be or create a star player.” But Punjab also saw a parallel rise of drug networks. “That damaged the sport,” he said, quietly.

Kabaddi’s peak visibility came after 2007, with the Shiromani Akali Dal. The government launched the World Kabaddi Cup, under the then deputy chief minister, Sukhbir Singh Badal.

“There was a time when people watched kabaddi more than IPL cricket matches, kabaddi players became professional sportspersons. Channels like PTC recorded high TRPs. Canada, UK, Iran showed interest,” Badal told ThePrint.

What started with video recordings of local tournaments, later converted into DVDs and cassette tapes and sent to NRI audiences abroad, switched to YouTube by 2008-09.

“The NRIs who invested their money into kabaddi wanted to see how the sport was being played. First, we used to provide them with CDs, which would take time to reach, then came YouTube. We started with one viewer, and now we have over 2.39 million subscribers,” said Gurbinder Singh, owner of Kabaddi 365, Punjab’s first Kabaddi broadcaster on YouTube.

But the momentum did not last. Subsequent governments did not continue the project, viewing it as politically owned. Stadiums built during that period fell into disuse, and institutional oversight weakened. Soon, allegations followed in headlines of black money, money laundering, and links between international drug networks and kabaddi clubs in Canada.

In 2014, the CBI sought records of the World Kabaddi Cup amid allegations of financial irregularities. Those who came under investigation included wrestler-turned police officer-turned kingpin Jagdish Bhola, Vancouver-based promoter of the Azadi Kabaddi Club Dara Singh Mathida, and former players Sarabjit Singh of British Columbia, Nirankara Singh Dhillon of Brampton, Ontario, and Harbans Sidhu of Toronto.

Also read: Shahjahanpur inter-caste couple who jumped — ‘All the talk now is about us being Brahmin-Dalit’

Economics of the turf

The cars parked outside the humble Moga village ground underline the sport’s popularity—and the money that it is generating. Among the Thars, Fords and Toyotas are cars that also double up as the players’ dressing rooms. What towers in this makeshift parking lot is a brand-new tractor that the winners will take home.

Kits, pain reliever spray, extra shorts—everything a player needs to survive a day of kabaddi lie in their vehicles.

Pasted on windshields are blown up and edited photographs of kabaddi stars, alongside posters of singer Siddhu Moosewala and Lakha Sidhana.

Young men sprint after players for selfies, filming reels for Instagram. This is what kabaddi stardom looks like in Punjab.

Behind the spectacle is months of financial planning. The Moga tournament was the initiative of four villages. Each village has four pattis, with each patti having 10 members on board.

“Every house had a parchi. Be it Rs.100 or 500. ‘NRI veer’ helped us. The responsibility was divided carefully. Who gets paid, who is invited, and what prizes are announced. This year, our budget was Rs. 20 lakh. The best player will win a tractor,” said Kuldeep Singh Sangha, village sarpanch.

For players, kabaddi remains one of the few ladders out of poverty.

Chirag Deen, 27, is finishing a set of push-ups on dusty ground before his team gets ready to raid the turf.

From Mahiyawala village, Deen’s story reflects how kabaddi can become a fast-track to social mobility.

“When I was growing up, nobody gave me their bike. Today, I have 40 bikes of my own. I have fan pages. And, I even got a Canadian visa in 15 minutes,” he said proudly, as his fans approached him for selfies.

Coaches and organisers ThePrint spoke to pegged the domestic kabaddi to be a Rs 100-crore industry. The big money in the sport came during the Badal government, according to Tejinder Singh Middukhera, general secretary of Punjab Kabaddi Association and World Kabaddi Circle Style Chairperson.

“Jo kabaddi hazaron ki thi, woh crores ki ban gai,” he said. However, only state-level competitions are recognised under the Federation. Much more happens at a rural scale.

Harpreet Singh Sudan, Director of Sports Department, Government of Punjab told ThePrint, that while the department has 37 disciplines to look at, the focus is more on sports promotion, rather than sports regulation.

“In the state, for kabaddi, there are several private kabaddi associations, block level kabaddi associations, along with state associations, and there is no requirement for them to be registered under the government,” he said.

Concerns regarding doping have been raised, however, Sudan clarified, that it is not the sports department that regulates the check, but the national associations, that maintain this close supervision.

For kabaddi games, there is no need for registration, prior permission, regulatory framework, or anti-doping mechanism. The promoters need to take permission from district administration, district commissioner, SDM, and the police.

But, when organised tournaments stopped under subsequent governments, regulations stopped.

“When big tournaments stopped, so did the control. Dope testing vanished. Associations weakened. Then, the private money from multiple unrecognised channels flooded in,” said Middukhera.

The void left by the NRIs and successive governments was now filled by gangsters.

Chauhan put it bluntly.

“Kabaddi requires funding. Prize money brings in players, visibility brings cash. That gave gangs the cover to extort, and influence turfs.”

Companies and powerful local businesses sponsor kabaddi tournaments because it gives them visibility, influence, and access to crowds, and sometimes cover for illegal money. Such promoters include tractor and motorcycle dealers, liquor contractors, and real estate developers. These sectors have big cash and political connections.

As concerns mount over the unregulated flow of money into rural sports, the Punjab government has announced a large-scale push to reclaim sporting spaces through state investment.

Chief Minister Bhagwant Singh Mann, in December 2025, directed officials to carry out a time-bound overhaul of sports infrastructure across the state, with work on 3,100 stadiums slated for completion by June 2026. The project, which will cost around Rs 1,350 crore, is part of the AAP government’s broader effort to bring village-level sports back under institutional control. Punjab’s sports budget for FY 2025-2026 was Rs 942 crore.

Chauhan, however, said he does not see a quick course correction in kabbadi.

“Extortion is normalised. With no international future in the sport, many players chase visas through kabaddi,” he added. “End of the day, kabaddi doesn’t give them long term bread and butter.”

Also read: Northeast Hoolock gibbons are facing extinction. The lesser apes are being counted now

Lives now changed

Inside a modest two-bedroom house in Jagraon, trophies nearly as tall as a person are stacked against the cement walls, collected over a decade of kabaddi tournaments. There were too many for Tejpal Singh’s house to hold. Some were placed inside gurudwaras. Others were given away.

“Our house was too small,” Jaswinder Kaur said, Tejpal’s mother.

Tejpal always dreamt of becoming a police officer but couldn’t score enough for the final selection round. So, he made kabaddi his life.

His wins paid for the house, the bed his mother sat on, the food on the table. Before his death, Tejpal had planned to get his house painted.

Fear has now replaced excitement in the village.

“Who will send their child to play kabaddi?” Jaswinder said. “All he did was dream. That’s what killed him.”

More than 100 km away, in another house, wedding flowers still hang drying on a wall. Rana Balachauria had been married just ten days before he was shot dead.

He put up photos on Instagram, and everybody congratulated him. His jaymal remains pinned to the wall of the room he renovated for the wedding.

Born in 1995, Balachauria wanted to build a kabaddi academy in his village so children stay away from violence and drugs. Fear never shaped his life, said his father, Rajeev Singh.

“He travelled all alone, trained alone, walked freely when strangers lined up for selfies. And that is how he got killed,” said Rajeev as Balachauria’s wife broke down.

After Rana was killed, his phone, jewellery, and belongings disappeared. What remains are the rooms he filled with ambition, awards, and certificates, and a young wife.

For decades, kabaddi was Punjab’s answer to addiction. For the Singh family, the promise feels broken.

“In Punjab, they used to say if you want to save your children from ‘chitta,’ then send them to play kabaddi,” said Jaswinder Kaur, wiping her tears, her eyes fixed on the trophies. “Now kabaddi has turned dangerous, where do we send our children now?”

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)