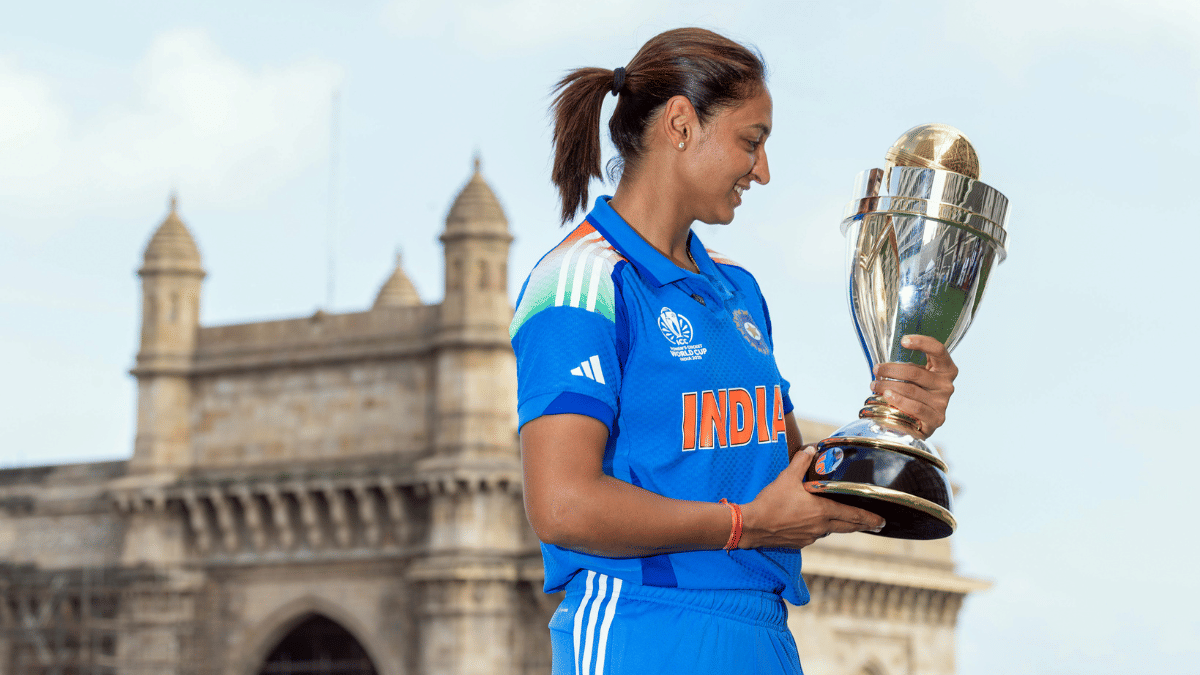

New Delhi: When captain Harmanpreet Kaur leapt in delight after completing the brilliant catch that dismissed South Africa’s Nadine de Klerk and handed India its first-ever Women’s ODI cricket world cup, she ignited a celebration that swept across the nation.

In the D.Y. Patil Stadium in Navi Mumbai, the team stayed on the ground until nearly 3 am, long after the floodlights had dimmed and the staff and players’ vocal cords had tired, soaking in the moment. Among them was Dr. Harini Muralidharan—the team doctor who calls that night “exhilarating” and “unforgettable”.

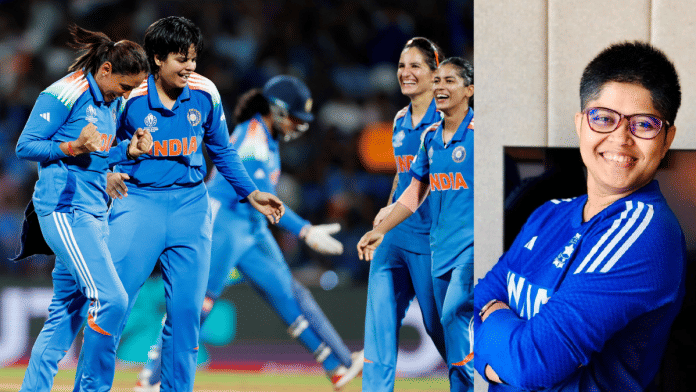

The Chennai-based sports medicine expert, who says her inclusion in the squad was “written in the stars”, offers a rare look into the science, discipline, and camaraderie that helped the team overcome the final hurdle.

“We took time just to be with each other and celebrate the moment. We didn’t leave the ground till almost 3 a.m. The celebrations carried on in the dressing room, and we finally went to sleep around 6 in the morning,” Muralidharan told ThePrint.

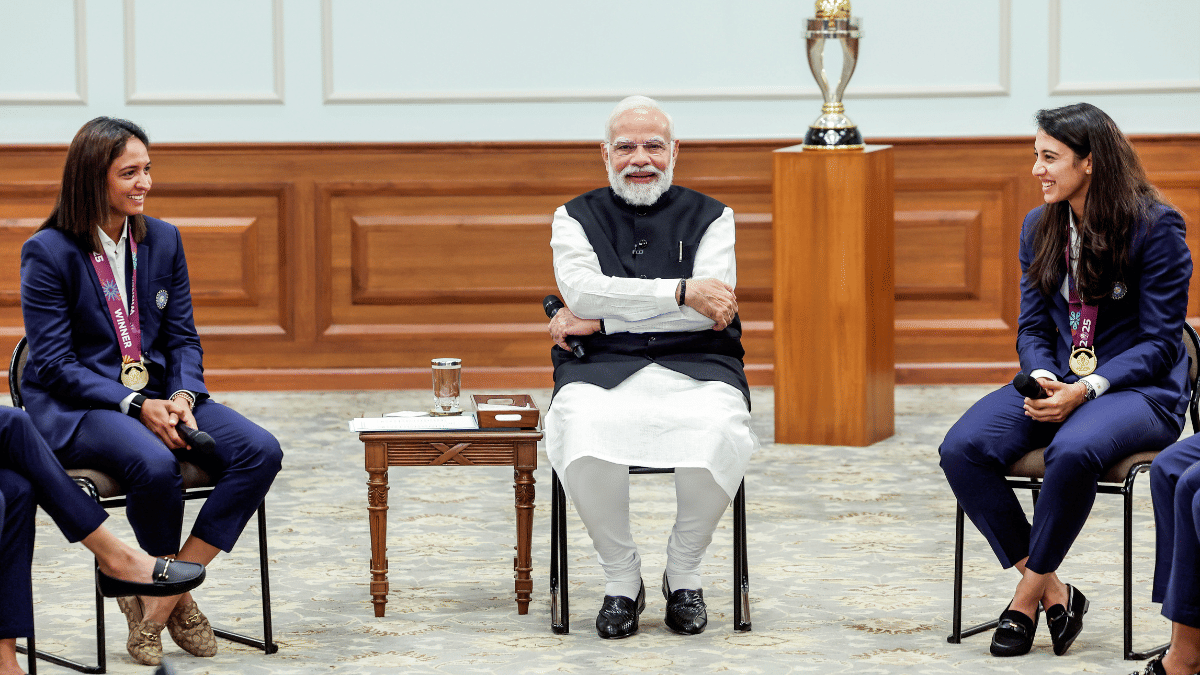

While the team celebrated, they did not forget to acknowledge the contributions of former stalwarts such as Mithali Raj and Jhulan Goswami. The two of India’s cricketing greats—who mentored and captained some of the current players—came within touching distance of lifting a world cup during their playing days, but it remained elusive.

Harmanpreet’s team had an unfinished business. They handed over the trophy to Jhulan and Mithali in heartwarming moments that became instant social media favourites.

The fact, Muralidharan said, that the team chose to celebrate first with those who paved the way for them speaks volumes about the character of these players.

“Exhilarating,” is how she described the dressing room atmosphere in one word. “There was tremendous camaraderie. Everyone was crediting one another for the win and for being team players.”

A freelance sports medicine practitioner from Chennai, Muralidharan was associated with the Royal Challengers Bengaluru’s women team for the last three years. She joined the Indian world cup squad just during the pre-camp phase.

When Muralidharan came on board, she didn’t shake up the schedule of the athletes, instead she remained a silent observer. Her goal, she said, was never to seek visibility or interfere with the athletes’ routines. Instead, she aimed to be available when needed while respecting the work of trainers, coaches, and other specialists.

“In setups like this, most practices are already pre-determined. Athletes follow specific routines, and the number one rule of any tournament, be it the World Cup, WPL, or even Ranji Trophy, is to ‘never mess with their routines’ before or during the competition,” she said. “Any change can disrupt fitness levels and performance.”

She calls her inclusion in the team a matter of destiny, saying it felt as though her presence with the team was “written in the stars”.

“It was an exact 40-day contract, and the squad was so welcoming. They never treated me like an outsider, and I managed to gel with them in no time,” said Muralidharan.

Also Read: Don’t see gender in criticism of women cricketers. Furore over Asia Cup loss is a positive sign

‘Family doctor’ for athletes

Joining as the official ‘team doctor’, Muralidharan described her role as similar to that of a family doctor. “Athletes touch base with us first for everything, and then the experts step in.”

Her primary responsibilities included injury management and prevention through diagnostics such as sports imaging, MRIs, and ultrasounds. A significant part of her role also involved anti-doping responsibilities, ensuring athletes remained compliant during treatments and recovery. Additionally, she dealt with sports psychology and nutrition, superficially.

“For nutrition, though dietitians handle most of it, we ensure that injured athletes follow a … diet and, during the season, that their carb loading and protein intake are adequate for recovery,” she explained. “We monitor these aspects while coordinating with the experts already in place.”

Muralidharan praised the fact the women’s cricket team has been working with an “incredible sports science unit” in addition to “three physiotherapists, two massage therapists, and a Strength and Conditioning (S&C) coach.”

India’s current S&C coach, A.I. Harrsha was associated with the team during the World Cup.

While Muralidharan emphasised that the players are now far fitter than they were four years ago, she noted that, unlike men’s cricket, there is currently no Yo-Yo Test in place for the women’s team.

“It was introduced a few years ago but later discontinued, so it’s not being actively used now. As for fitness standards, that falls under the S&C department’s expertise,” she said.

Muralidharan said fortunately no situation popped up where she had to step in. The campaign went smoothly, but star opening batter Pratika Rawal’s injury did shake the team up for a brief while.

The doctor said she isn’t allowed to get into the details of Rawal’s case as it would be breaking confidentiality, but the team didn’t see it as a setback, instead God’s plan.

“Pratika contributed immensely to bringing the team to the qualifiers. And after she was gone, when Shafali (Verma) came in. I think Shafali coming in and being the player of the match in the last game, I think it was all part of God’s plan to make us the champions this year,” Muralidharan said.

“As for Pratika, she is doing whatever needs to be done for her rehab, with all of the capable physios. So, she will be back soon.”

‘Luck by chance’

Choosing sports medicine as a career wasn’t Muralidharan’s plan. Torn between forensics and emergency medicine, she was casually advised by her father, in a passing conversation, to consider sports medicine.

“The idea stuck with me, so I reached out to Mr. Shankar Basu, who was then the S&C coach for the Indian men’s team. He runs a center in Chennai and suggested that I do an internship before deciding,” she said.

Within a month of interning, Muralidharan said, she was completely captivated by the field. She then applied for a master’s degree at Queen Mary University, London, and returned to India during the peak of COVID-19 on a Vande Bharat flight.

For two years, she found herself without work, as all sporting activities were halted. Despite sending countless CVs, she received no responses.

Though tempted to join a hospital as a sports medicine physician, she knew that doing so might make returning to sports difficult. Eventually, luck turned in her favour. Over two years later, she learned about an opening at the RCB, applied, went through a couple of interviews, and was selected.

While joining the RCB was still a believable milestone, being named the national team doctor felt surreal for her, something she couldn’t believe until she actually joined the camp.

“I have been working with the RCB for about four seasons now, and through that circuit, I have met quite a few people. A couple of months ago, the Indian women’s team’s manager called saying there was an opening and asked me to send in my CV. I did, but with no expectations at all,” she recalled.

After sending her application, there was complete silence for nearly three months. Muralidharan had almost accepted that she wouldn’t be selected. After all, it was the national side. But just 10 days before the tour began, she received the call confirming her selection. “It was surreal; I couldn’t believe it, just couldn’t.”

A male-dominated field

Despite her achievements with both the RCB and the national side, Muralidharan acknowledged that sports medicine remains a “male-dominated” field. “There aren’t many female sporting teams that have a dedicated doctor in place.”

“Another issue is the lack of regulations. In cricket, there are clear guidelines requiring a doctor, and they recognise the importance of that role. But in other sports, such mandates are still missing.”

She admitted that there are several enterprising women breaking into the field, but their numbers are still far lower than their male counterparts.

Muralidharan is optimistic, though, believing that with the growing visibility of women’s cricket, and women’s sports in general, more female sports physicians will join the profession. “It’s a work in progress,” she said. “And I do see it happening.”

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: WPL changing cricket crowd culture. Kids in stands scream Jemimah, men now say ‘batswoman’