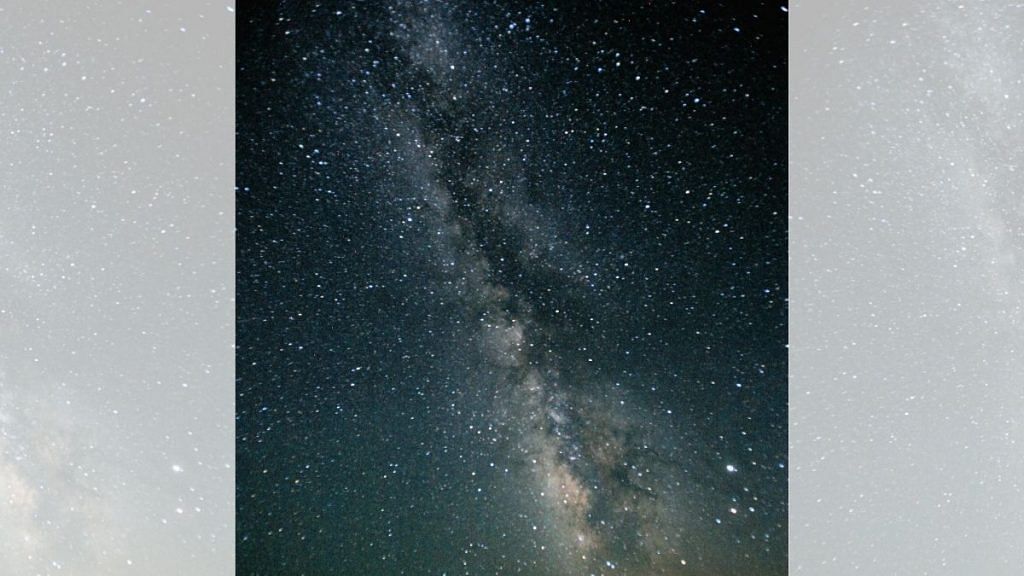

New Delhi: Astronomers, including those from the Indian Institute of Science, have discovered one of the longest structures ever observed in our galaxy — a massive filament of atomic hydrogen gas located about 55,000 light-years away.

The structure has been named Maggie.

About 13.8 billion years ago, the universe was born in a massive explosion known as the Big Bang that gave rise to the first subatomic particles. Hydrogen was formed about three hundred seventy thousand years later.

Hydrogen is the building block of stars, which fuses hydrogen and helium in their core to create all the heavier elements like carbon, oxygen, nitrogen etc,, which have a higher number of protons and neutrons.

While hydrogen remains the most pervasive element in the universe, it can be difficult to detect individual clouds of hydrogen gas in the interstellar medium. This makes it difficult to research the early phases of star formation, which would offer clues about the evolution of galaxies and the universe.

The discovery of Maggie may help determine how the two most common hydrogen isotopes converge to create dense clouds that give rise to new stars. The isotopes include atomic hydrogen (H), composed of one proton, one electron, and no neutrons, and molecular hydrogen (H2)—or Deuterium— which is composed of one proton, one neutron and one electron.

Only the latter condenses into compact clouds that will develop frosty regions where new stars eventually emerge. Read more.

Death of supergiant star captured for the first time

For the very first time, scientists have captured in real time the dramatic end to a supergiant star’s life located 120 million light-years away.

Using two telescopes, the team Northwestern University and the University of California, Berkeley, was able to watch the red supergiant during its last 130 days leading up to its collapse into a Type II supernova.

The observation is a breakthrough in the understanding of what massive stars do moments before they die. Direct detection of pre-supernova activity in a red supergiant star has never been observed before in an ordinary Type II supernova.

Researchers first detected the doomed massive star in the summer of 2020 via the huge amount of light radiating from the red supergiant. A few months later, a supernova lit the sky.

The team quickly captured the powerful flash and obtained the very first spectrum of the energetic explosion. The data showed direct evidence of dense circumstellar material surrounding the star at the time of explosion.

The team continued to monitor the object after the explosion. Based on data , they determined the red supergiant star, located in the NGC 5731 galaxy about 120 million light-years away as seen from Earth, was 10 times more massive than the Sun. Read more.

Also read: Not just RT-PCR tests, now your ‘smart’ masks will also tell you if you have Covid-19

Unusual eyes found in 95-million-year-old crab fossil

Researchers from Yale and Harvard have discovered unusually large optical features in a 95-million-year-old crab fossil, Callichimaera perplexa — a species first discovered in 2019.

The crab was about the size of a quarter, featuring large compound eyes with no sockets, bent claws, leg-like mouth parts, an exposed tail, and a long body.

Previous research indicated that it was the earliest example of a swimming arthropod, with paddle-like legs, since the extinction of sea scorpions more than 250 million years ago.

For the study, the researchers analysed nearly 1,000 living crabs and fossils, including crabs at different stages of development, representing 15 crab species. The researchers compared the size of the crabs’ eyes and how fast they grew.

Callichimaera topped the list in both categories. Its eyes were about 16 per cent of its body size.

he eye size of these crabs are interesting because this means that the organisms were very good predators, who used their eyes when hunting. Sow-growing eyes tend to be found in scavenger crabs that are less visually reliant. Read more.

DNA in lice ‘cement’ helps decode ancient human history

Scientists have for the first time extracted human DNA from what is called the ‘cement’ head lice used to glue their eggs to human hair thousands of years ago. This could provide an important new window into the past.

For the study, scientists from the University of Reading recovered DNA from cement on hair taken from mummified remains that date back 1,500-2,000 years. This is possible because skin cells from the scalp become encased in the cement produced by female lice as they attach eggs, known as nits, to the hair.

Analysis of this ancient DNA — which was of better quality than that recovered through other methods — has revealed clues about human migration patterns within South America. This method could allow many more unique samples to be studied from human remains where bone and tooth samples are unavailable.

Until now, ancient DNA has been extracted from dense bone from the skull or from inside teeth, as these provide the best quality samples. However, skull and teeth remains are not always available, as it can be unethical or against cultural beliefs to take samples from indigenous early remains, and due to the severe damage destructive sampling causes to the specimens, which compromise future scientific analysis.

Recovering DNA from the lice ‘cement’ is therefore a solution to the problem, especially as nits are commonly found on the hair and clothes of well preserved and mummified humans. Read more.

Gene analysis reveals story of lychee cultivation in China

Lychees have been grown in China since ancient times, with records of cultivation dating back about 2,000 years.

Using genomics, scientists have now gained insights into lychee’s history. The team from the University at Buffalo was able to trace the origin and domestication history of lychee. They demonstrated that extremely early and late-maturing varieties were derived from independent human domestication events in Yunnan and Hainan.

To conduct the study, scientists produced a high-quality “reference genome” for a popular lychee variety called ‘Feizixiao’, and compared its DNA to that of other wild and farmed varieties.

The research shows that the lychee tree was domesticated more than once: Wild lychees originated in Yunnan in southwestern China, spread east and south to Hainan Island, and then were domesticated independently in each of these two locations.

In Yunnan, people began cultivating very early-flowering varieties, and in Hainan, late-blooming varieties that bear fruit later in the year. Eventually, interbreeding between cultivars from these two regions led to hybrids, including varieties, like ‘Feizixiao’. Read more.

Also read: Sampling DNA from air could help track animals, transform wildlife monitoring