New Delhi: Fossilised lizard and python remains found in the region of Haritalyangar, Himachal Pradesh have given scientists important clues to the climatic conditions in the area 9.1 million years ago. The coexistence of the two reptile species has also revealed a wider distribution of the clade — descendants of a common ancestor — in this southern Asian territory.

The findings were published in this month’s issue of the Geobios journal.

Lizards and snakes are considered to be excellent indicators of climatic conditions in the past, as being cold blooded, their distribution, richness, and diversity are in a good measure dependent on temperature and climatic conditions.

The fossils found from a Miocene hominid locality indicates the mean annual temperature must have been high in the region at that time (not less than 15–18.6°C), similar to the mean annual temperature in this area today.

While Miocene is the time period between 23 and 5 million years ago, when temperatures started getting warmer and continents began moving towards their present location, hominids are great apes of a family which include human ancestors.

“We humans , Homo sapiens, depend upon fossils to understand where we are coming from. From these findings we can understand our roots,” Dr. Ningthoujam Premjit Singh, a vertebral paleontologist, who led this research, told ThePrint.

He added: “India is known as a hotspot for snakes and lizards. It takes a fossil 1000 years to develop. In contrast to Pakistan and Europe, India has not discovered as many fossilized reptiles in the last 18 million years.”

Also read: Indian scholar at Cambridge solves 2,500-yr-old Sanskrit algorithm problem in Panini’s text

Proof of biodiversity

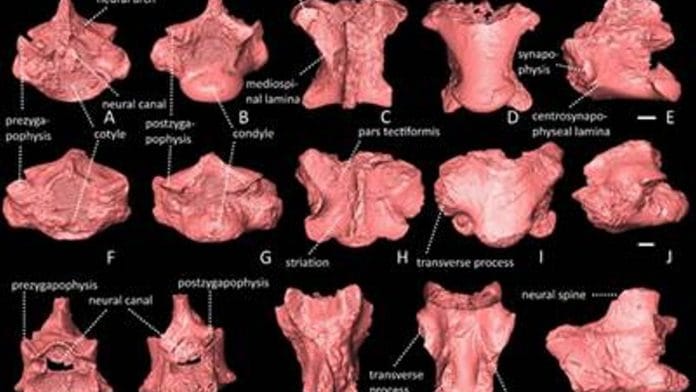

The recent findings from the Haritalyangar region are also important because the lizard genus whose fossil was found, Varanus, reveal past biodiversity here, since varanids have a limited fossil record in Asia. Python fossil finds from South Asia too remain poor, except for some records in Pakistan and Kutch.

The research was conducted by the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG), Dehradun, an autonomous institution of the Department of Science and Technology (DST), in association with researchers from Panjab University (PU) Chandigarh, Indian Institute of Technology Ropar (IIT Ropar) Rupnagar, Punjab, India, Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia.

Led by Singh, the team of researchers included Dr. Ramesh Kumar Sehgal and Mr. Abhishek Pratap Singh from WIHG, Dr. Rajeev Patnaik, Dr. Kewal Krishan and Shubham Deep from PU, Dr. Navin Kumar, Mr. Piyush Uniyal and Mr. Saroj Kumar from IIT Ropar and Dr. Andrej Cernansky from Comenius University.

While the dig was started by Dr. Rajeev Patnaik, a geology professor of Panjab University, Singh said Patnaik later handed over the research to his team, as they specialised in reptiles. It took the team nearly six years to complete the research, he added.

“It is quite easy to find a big fossil of reptiles, buffaloes which are seen through naked eyes, compared to the research of microfossils which need equipment like a microscope to even see through it. But still, India has not been active in finding even the big fossils in the past years,” said Singh, lamenting the general deficit in paleontology research in India.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Why did methane levels shoot up in Covid yr? Warm weather, and less pollution