James Tooley is a British professor who was put in an Indian prison for four months on false charges because a colleague in his NGO refused to pay a bribe.

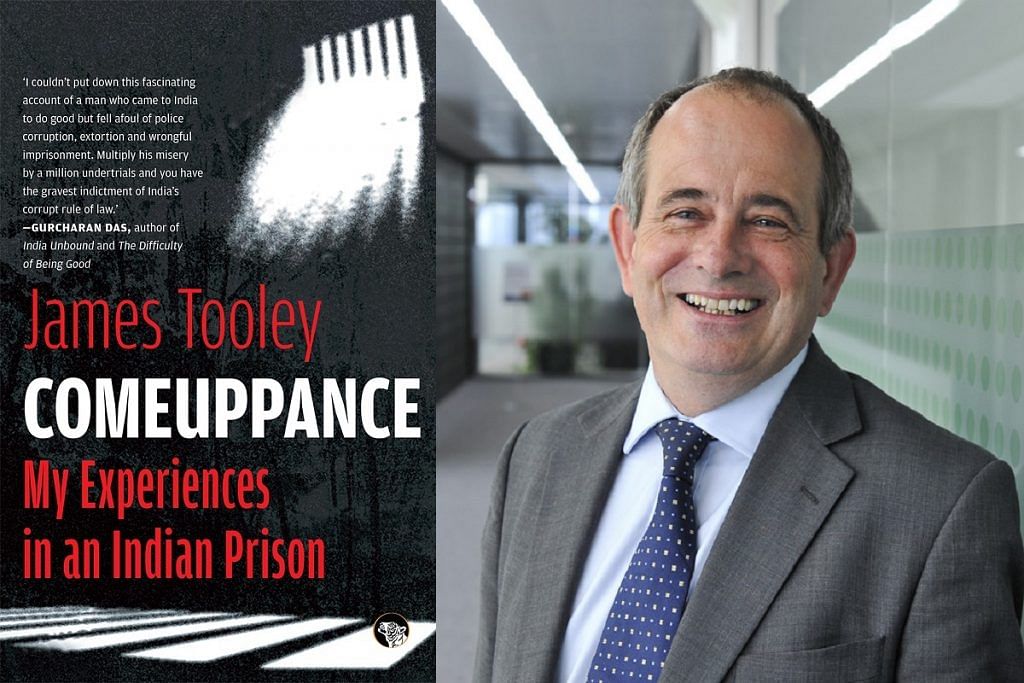

Professor James Tooley was a reasonably famous man. He taught at a reputed British university, was an award-winning scholar, a champion of low-cost private education known for creating models of innovation across South Asia and Africa.

He had his life’s work covered in Newsweek, the Economist, the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal, as well as in documentaries for the BBC and PBS.

Then, one night in March 2004, all that changed forever. That night, he was arrested by one Mrs Mantra, deputy superintendent, CID, Hyderabad Police, and her team of subordinates. There was no warrant; the case was fabricated. The professor was easy prey in the jaws of rogue police officials.

‘Comeuppance: My Experiences in an Indian Prison’ (Speaking Tiger, 2016) is his true story.

The book is not an angry account of a man wronged, deprived, and humiliated. Not a single sentence smells of a smart play of the victim card, despite losing the love of his life for no fault of his.

A tale of incompetence and injustice

The book is a distressing yet absorbing chronicle of what India’s bureaucracy – police, prosecution, judiciary and prison – did to an honourable man for more than four months. Why? Just because a colleague in his NGO, Educare Trust, refused to pay a bribe to a greedy bureaucrat a decade ago.

This is a tale of incompetence, manipulation, exploitation, imprisonment, injustice, despair and corruption. And it reeks of lack of accountability from the national capital to the states. There is a side story of how Tooley’s own lawyers abandoned him at the most crucial times.

If the conduct of the CID cops was pathetic, that of the prison officials was cruel and barbaric. The bigger tragedy is the criminals in uniform of both the departments managed to hoodwink the judiciary without caring for the consequences.

The lives of India’s undertrials

The book is both a memoir and a social anthropological study of the lives of undertrials, who account for 67 per cent of people in Indian jails. This share is extremely high by international standards –it is 11% in the UK, 20% in the US and 29% in France.

The writer, despite the ignominies heaped on him, finds his humanity intact to see the extraordinary kindness of the other prisoners, who are also victims of police corruption and an unaccountable criminal justice system.

If this is what has happened to a British national who is highly educated and reasonably famous, what is the plight of 2.5 lakh undertrials who are rotting in India’s prisons today? Indian prisons are overcrowded and understaffed. Unless these issues are dealt with, prisons will remain hellish for the socio-economically disadvantaged.

According to the Prison Statistics India 2015 report by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), India’s prisons are overcrowded, with an occupancy ratio of 14% more than the capacity. With over 3.1 crore cases pending in various courts as of 31 March 2016, jails across the country will remain overcrowded in the absence of any effective systemic intervention.

At the end of 2014, nearly 43% of the undertrial population had been detained for more than six months to more than five years. Many spent more years in prison than the actual term they would have served had they been convicted.

India’s criminal justice system needs a complete redesign to bring in the elements of trust, accountability, and time-bound case disposal. With the highest per capita laws in the world, India can’t afford to let it crumble under its own ever-increasing weight.

The members of the elite Indian Police Service need to make their presence felt in the current scheme of things. Big feasts, durbars, PowerPoint presentations, and golf can wait. The dirge of political interference can wait.

(Basant Rath is 2000 batch IPS officer from the Jammu and Kashmir cadre. Views expressed are personal.)