India has often talked about its success in reducing poverty. The World Bank’s new estimates say India has made big progress in cutting extreme poverty, defined by people living on less than $3 a day. These figures suggest poverty is now very low in the country.

But if we look at how people spend their money, a different story emerges. Many families may be just above the poverty line, but their lives still look poverty-stricken. They spend most of their earnings on food and basic needs. This is why simply counting how many are below a line can be misleading.

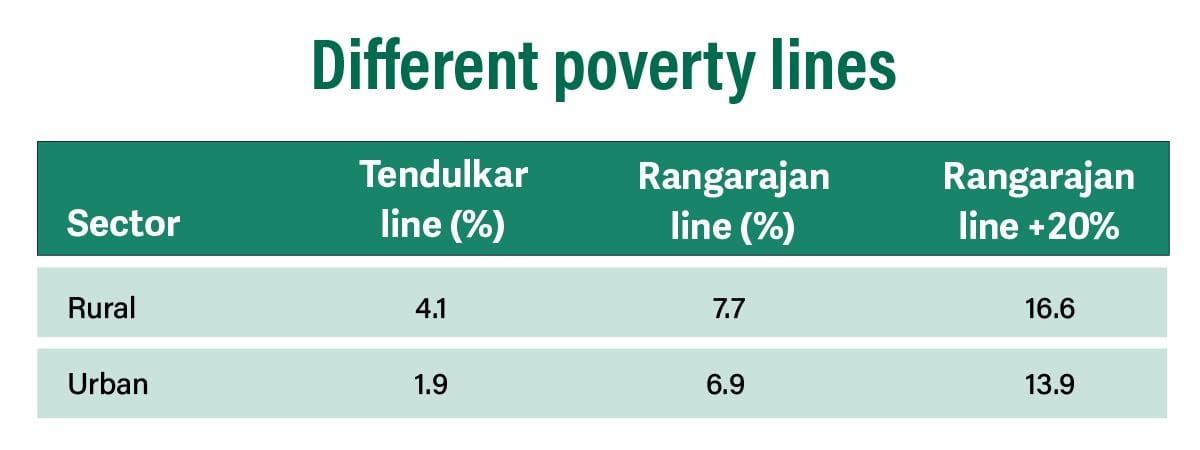

In India, poverty rates can vary depending upon which estimation method you are using.

Using the Tendulkar poverty line, rural poverty stands at just 4.1 per cent and urban poverty at 1.9 per cent, according to calculations based on Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2022–23 data.

But the Rangarajan line, which includes non-food expenditure, particularly on essential items beyond just nutrition, shows a different picture. Rural poverty almost doubles to 7.7 per cent, while urban poverty more than triples to 6.9 per cent.

When you raise the Rangarajan line by 20 per cent to adjust for higher costs, poverty goes up further to 16.6 per cent in rural areas and to 13.9 per cent in urban areas.

This shows that poverty is not a fact. It depends on how you define it.

How the rich and poor spend their money

If poverty was ending, we would expect people’s spending to reflect that. But data shows the opposite.

Rich households spend their money very differently from the poor ones. In urban areas, the top 5 per cent spend only 28 per cent of their budget on food. About 20 per cent goes toward durables and goods that improve their living standards. Even the top 20 per cent spend only about 32 per cent on food.

In rural areas, the richest spend less than 39 per cent of their budget on food and more on durables and savings.

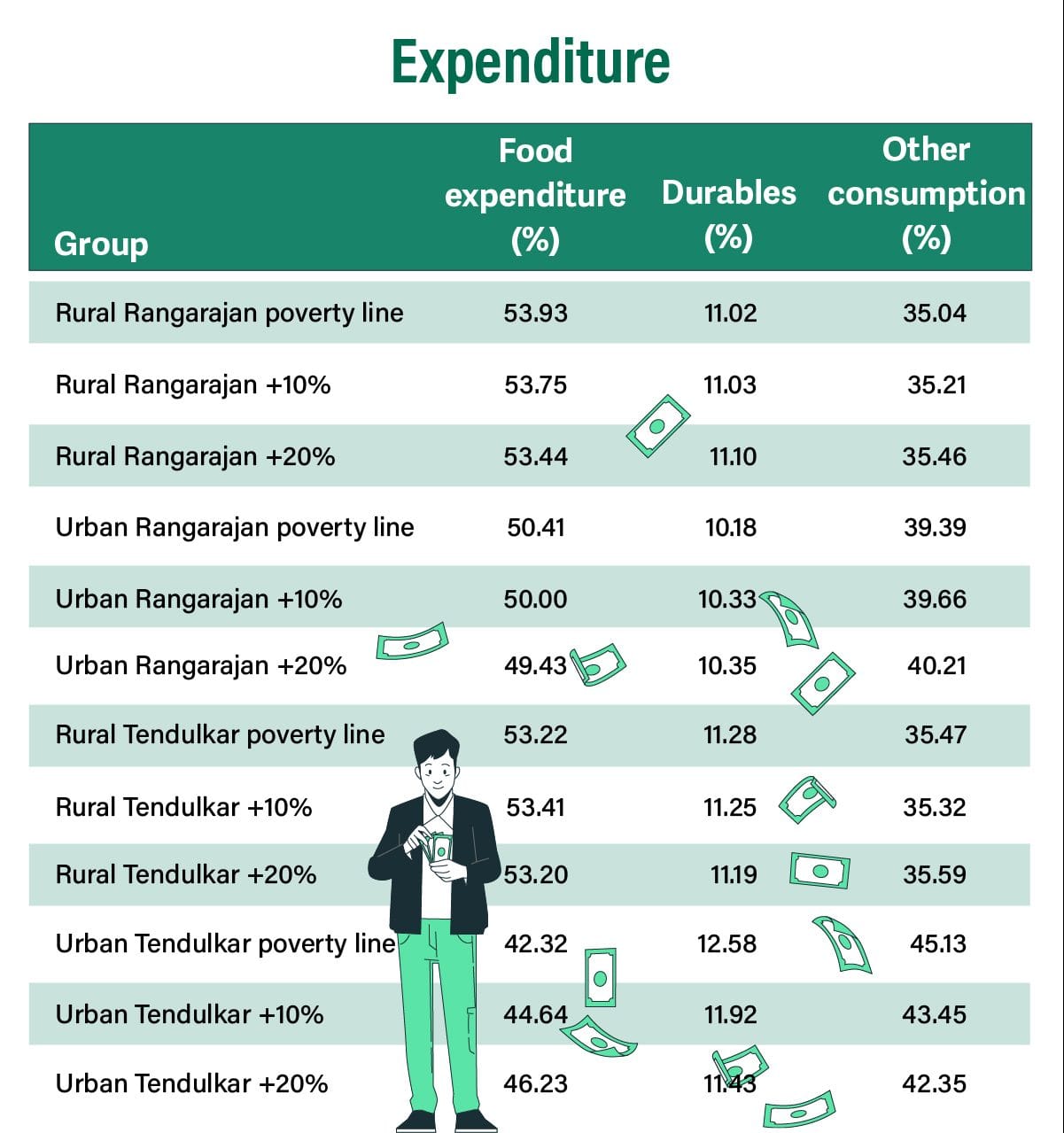

By contrast, people on or just below the poverty line spend over half their income on food. Even when they cross the line, their spending patterns hardly change.

The above table shows that even when households are above the poverty line, they still spend much like the poor. Food takes up most of their budget, while spending on durables and savings are very low.

Also read: Does India need a new poverty line? Depends on what we’re measuring it for

The near-poor

People who are just above the poverty line are often called the near-poor. Even if they are not counted as poor, it doesn’t mean their lives are secure. Any health problem, job loss, or inflation can easily push them back below the line.

At the same time, the richer deciles spend less on survival and more on building assets and comfort. This gap in spending shows that moving slightly above the poverty line does not mean a family has escaped hardship.

Looking beyond the line

When we talk about poverty mainly by counting how many people are below a line, it can give an impression that everyone above that line is comfortable. But many households just above the line still find it hard to make ends meet. Most of what they earn is spent on food and other basic needs, much like poorer families.

While they are not counted among the poor, their lives remain uncertain. A small setback, and they can slip back into poverty. This is why it is important to look beyond any single poverty line and focus on how people actually live.

What can be done

Poverty is not just about crossing a line. It is also about whether people can stay above it with some security and dignity. If India wants real progress, it needs to look more closely at how families spend and cope.

Any serious effort should consider what it really costs to eat well, stay healthy, and send children to school. It should also recognise that many people who are not officially poor are still living on the edge.

Progress should not be measured only by how many people cross a threshold. It should be measured by whether more people have a chance to live decently without fear of falling back.

The author is Assistant Professor of Economics and Sustainability, IMT Ghaziabad. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)