Live lambs had been hustled aft, over the fantail of the warship DD-603, for slaughter; the deck covered over with Persian rugs and an exotic tent; coffee brewed endlessly over charcoal braziers set alight over the explosives in the gun turrets, all this watched over by seven-foot-tall Nubian slaves with scimitars swinging from their belts. As King Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud, prayed and took counsel from his court astrologer, Majid Ibn Khataila, his sons Amir Mohammed and Amir Mansur sneaked below deck to watch Too Many Girls, a 1940 movie briefly famed for a risque scene involving a woman’s dress, a men’s dormitory and Lucille Ball.

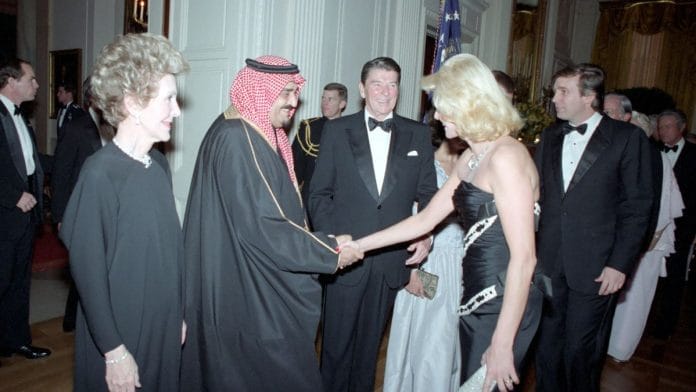

Eight decades ago this year, US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt met with the Saudi king on Egypt’s Great Bitter Lake to hammer out the deals that have held up the modern economy: Guaranteed American military protection of the Persian Gulf, in return for an endless supply of cheap oil.

There are growing signs, though, that the Great Bitter Lake deal is dying. Last week, news broke that Saudi Arabia had been compelled to abandon work on The Line—the kingdom’s science-fiction fantasy city, that was intended to rise out of the desert in defiance of both the laws of prudent finance and physics. The Line, planned as a 170-kilometre-long, 500-metre all-mirror-glass structure, has already blown a $50 billion hole in the country’s $1 trillion Public Investment Fund.

This month, when Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman visits Washington, observers expect a deal over sales of F35 combat jets to the kingdom, in return for recognition of Israel. The Saudi side, though, is likely to ask for a much wider deal, including ironclad security guarantees, a civilian nuclear deal and deeper technological cooperation to build a post-oil future.

Low oil prices, a centrepiece of President Donald Trump’s economic policies, have led the Saudi budget deficit to expand dramatically. The United States has meanwhile become the world’s largest producer of crude oil, pumping out more than Saudi Arabia and ensuring oil prices will not rise. Trump has also been successfully arm-twisting countries into committing to purchases of US oil and gas, using geopolitical goodwill Saudi Arabia just doesn’t have.

The House of Saud, some pessimists believe, is starting to resemble the court of Louis XIV, the Sun King—the seventeenth-century monarch’s expensive passions for love and warmaking laid the foundations for the French Revolution, corrupting the élite and blowing a hole in the treasury.

Also read: Sudan shows what happens when the world is happy to let mass killers rule

The line that won’t hold

Even if Saudi oil doesn’t power the world any longer, the Kingdom’s advantages are indisputable: The country’s wells have more oil, and far greater varieties of it, at a lower price than anywhere else. The natural pressure of Saudi oil means the average well in the country can produce 3,000 barrels a day, compared to the 27 that can be lifted to the surface in the United States. That means it costs the Saudis around $4 to extract and produce a barrel of oil, while US shale can be as expensive as $35-50. The multiple fuel grades Saudi Arabia is home to can be used to make gasoline, jet fuel, diesel and petrochemical feedstock.

The most important thing is the Kingdom’s enormous reserves. The country’s national oil companies hold some 90 reserves, sprawled across 1.5 million square kilometres. Only 17 of those are in production. Saudi Aramco alone can ramp up production on demand, bringing online its 12 million barrels per day of spare capacity as it did in 1986 and 2011.

And that’s also its core problem: There’s just too much oil to sustain the Kingdom’s dreams. Last year, financial intelligence firm Fitch warned that revenues did not exist to sustain Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, a plan for a post-oil future built around projects like The Line. The reasons for that aren’t opaque. To attract large Asian buyers like India and China, war-hungry Russia has been offering discounts of $2-4 per barrel. Last month, Saudi Arabia began offering Asian buyers its own discounts of over $2.20 per barrel.

For Saudi Arabia to balance its budget, estimates released in 2023 suggested, it needed prices of around $96.20 per barrel. Leaving aside the fact that this would undermine Trump’s domestic economic promises, the price seems unachievable given the volumes of Russian crude on the market.

There’s no doubt, experts Dag Harald Claes, Andreas Goldthau, and David Livingston write, that all major oil exporters except the United States would like to end the implosion of prices which began in 2014. For Russia, Venezuela, and even Saudi Arabia, prices of around $100 per barrel would be ideal, though for different reasons. There’s no prospect of that happening as long as US production is capped on the market.

Even though the traditional producers could seek to put American shale out of business by letting prices fall even further, that would mean they had even less cash in hand to build megacities or fight wars.

Saudi Arabia’s sandcastles

There’s little doubt that Saudi Arabia contributed to its own problems, driven by leadership hubris and poor advice. The Line is a case in point. The speed at which the project’s execution was envisaged, journalist architect Alison Killing writes, would have needed a container to dock at Neom’s small port every eight minutes, bearing the equivalent of France’s entire production of cement and the complete output of the world’s largest cladding manufacturer. Elements of the project, like The Chandelier, a 30-storey building to be suspended upside-down from a bridge, seemed to defy the laws of physics.

As the money flowed, designers blithely skipped over obvious problems. The project envisaged a railway line that could carry residents to a brand-new airport in 20 minutes. Luggage wouldn’t fit on the high-speed railway line, though, so passengers were required to deposit their bags outside their doors up to eight hours in advance.

The logistics of sewage on the upside-down building were even more bizarre. Toilets were to be drained by hundreds of shuttle cars running back and forth, picking up the sewage on retractable bridges, Killing reports.

Even as PR firms for The Line cast it as a kind of civilisational turning point—the most important, it was said, since the Roman emperor Marcus Ulpius Traianus seized Arabia to safeguard Rome’s trade with India, and laid the ground for great cities like Petra, Hejra and Mada’in Saleh—voices of caution were mostly ignored. The Line was to power Saudi Arabia’s post-oil fortune in Artificial Intelligence and robotics.

For Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman, the end-state was a Saudi Arabia that would leave behind its dependence on both hydrocarbons and theocracy—though its absolute monarchy would remain in place, unchallenged.

Also read: America gifted China its rare-earth monopoly — and India helped too

An unwelcome awakening

Though a violent revolution in the region is profoundly unlikely, there are signs that Saudi Arabia is distancing itself from some of its dreams. Earlier this year, mixed-gender nightclubs were shut in Riyadh and Jeddah, and a new unit was set up at the Interior Ministry to enforce religiously-sanctioned behaviour. Local Right-wing clerics like Indonesian-origin Sheikh Assim Al-Hakeem—known to his young followers as “Sheikh Awesome”, writes scholar James Dorsey—are resurfacing rapidly.

Saudi Arabia is also making backup arrangements for regime survival. The mutual-defence agreement signed between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia is, in essence, a hedge against America reneging on its promises to protect the Kingdom. In 2019, America chose to do nothing when Saudi oil facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais were targeted by Iranian drones—fearing a major conflict would send oil prices skyward.

Fearing the reaction of young Saudis incensed by the war in Gaza, Saudi Arabia has also delayed recognising the state of Israel. The Kingdom has also sought to normalise its relationship with Iran. Helped by diplomatic intervention from China. The scholar Sultan Alamer suggests that Saudi Arabia understands it needs to hedge its great power relationships, rather than count on the ageing, eight-decade guarantee from America.

There was just one single thorn left after the warm meeting between the King and the President at Great Bitter Lake. The Jews of Europe, President Roosevelt explained, were seeking refuge in Palestine. The King thought he had a better idea.“Give them and their descendants the choicest lands and homes of the Germans who had oppressed them.” “Amends should be made by the criminal, not by the innocent bystander.”

Even though this problem was never resolved, the relationship flourished: Through the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, 1967 and 1973, through the Iraq wars of 1998 and 2003 and through the seismic events of 9/11, America and Saudi Arabia stood together.

The black, stinking sludge that joined them, though, is today wearing thin.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. His X handle is @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)