Fairy tales also read like this: Like a cursed jewel, Abdullah Öcalan was flown through the night to a lonely island in the Sea of Marble, and abandoned behind great walls guarded by dragons. For 10 years, he would be the only prisoner on the Turkish island Imrali, locked in a cell guarded by over a thousand soldiers. Fishermen who strayed too close to its shores were warned away by naval ships. Even the small colony of small-time thieves and swindlers imprisoned on the island were evacuated before his arrival, together with their herd of cows and chickens. For years, there would be no word from the prisoner.

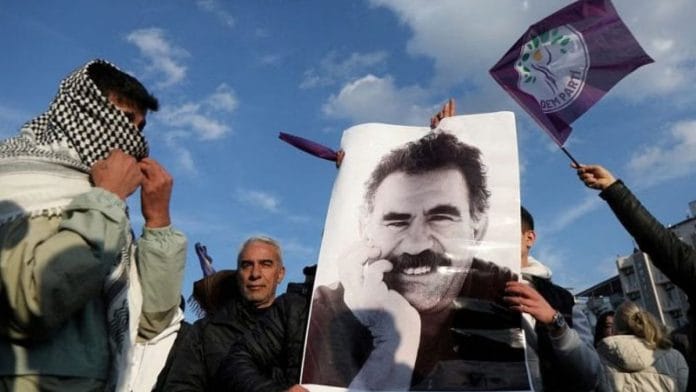

Last week, though, Öcalan called for his Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, or Kurdish Workers’ Party, to disarm and end its long war to carve an independent state out of Türkiye—raising hopes that one of the longest insurgencies in the world might finally come to an end. There’s a reason, though, to be sceptical: Efforts to end the fighting in 1993, 1995-1996, and 2013-2015 all led nowhere.

Each time, efforts to secure peace were undermined by Türkiye’s failure to politically address festering Kurdish resentment over issues of ethnic discrimination and identity. Türkiye’s establishment believes time is on its side, and it may well be right. The use of the Kurdish language has diminished, analyst Zuzanna Krzyżanowska points out, and the minority’s integration in Türkiye’s national politics has grown.

The cost of maintaining control hasn’t been trivial, though. Türkiye has been forced into costly military campaigns in Syria and Iraq, as well as an endless campaign of attrition against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) at home. Events have repeatedly shown, moreover, that this hard-won status quo can be easily swept aside.

“Let there be no torture or anything,” a dazed Öcalan had mumbled as Turkish special forces personnel herded him onto a jet in 1999, to face trial in Türkiye. “I love Turkey and the Turkish nation and I want to serve it.” Even the humiliation of that moment of utter defeat, though, didn’t bring an end to the story.

A war beyond borders

Six months ago, terrorists Mine Sevjin Alçiçek and Ali Örek stormed the headquarters of Türkiye’s aerospace giant, Türk Havacilik ve Uzay Sanayi—demonstrating the PKK’s continuing ability to bring war home. For years before the attacks, Türkiye’s military had been using drones and combat jets to bombard PKK positions across the border in Syria and Iraq. Even though the US supported Türkiye’s counter-terrorism concerns, expert Aaron Stein notes, it was also reliant on PKK-allied Kurdish groups for its war against the Islamic State.

As Türkiye prepared the offensive that would lead an Islamist proxy, the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, to power in Damascus last year, it also applied its mind to this problem. Far-right Nationalist Movement Party leader Devlet Bahçeli, a key ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, reversed his long-standing calls for executing Öcalan, and instead offered him an amnesty if the PKK disbanded.

The offer—made just a day before the attack on Türk Havacilik—was driven by events in Syria. To secure its gains in Syria, Türkiye needed a political agreement with the militia that controls the US-backed Kurdish enclave in Syria, the Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, or People’s Defense Units. The government of US President Donald Trump is preparing plans to withdraw its remaining troops from the Kurdish enclave, leaving Türkiye the dominant regional power. A peace deal with the PKK would, obviously, ensure Trump’s plan could go ahead.

Late last year, thus, Öcalan met with leaders of the pro-Kurdish Halkların Eşitlik ve Demokrasi Partisi, or People’s Equality and Democracy Party, at his island prison, Imrali. The meeting led to a seven-point charter for engagement between Türkiye and the PKK. Türkiye’s intelligence services are since believed to have facilitated a number of meetings between the two sides, despite the Türk Havacilik attack.

For President Erdoğan, the stakes are high. The last 10 years have seen his Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or Justice and Development Party, take a hardline anti-Kurdish position. The 2023 elections saw it circulated doctored videotape alleging that opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu had the backing of the PKK. To explain a peace deal with the PKK to the AKP’s ethnic-Turk chauvinist base is no small ask, as scholars Alper Coşkun and Sinan Ülgen have argued.

Yet, Erdoğan likely considers the risk worth taking. Türkiye’s constitution bars him from running for a third term, except in one circumstance, an early election called by 360 of the country’s 600 members of Parliament. To meet that threshold, though, the DEP (Equality and Democracy Party) will have to vote with the AKP and its allies. A historic peace deal with the Kurds might just give the Left-wing DEP and the right wing led by the AKP reason to ally.

Also read: Lalit Maken to Tahawwur Rana—India’s first extradition battle still poses tough questions

The pitfalls ahead

Will the convergence of geopolitical imperatives and political opportunity ensure a successful deal? To answer that question, one needs an understanding of why the Kurdish insurgency has been so durable. Ever since Türkiye’s 1923 revolution brought modernising nationalists to power, historian Paul White records, Kurdish feudal leaders staged a number of insurgencies aimed at protecting the region’s power structure and identity. This early phase of insurgency, which came amid efforts to eradicate the Kurdish language and even names, culminated in the 1938 massacre of tens of thousands by Türkiye’s military in Dersim, now renamed Tunceli.

From the 1960s, as Türkiye entered a prolonged military rule, Kurdish resistance resurfaced, this time shaped by the Left. The backwardness of Türkiye’s ethnic Kurds, who make up about one-fifth of the country’s population, spurred a series of large-scale strikes and demonstrations. Türkiye’s organised Left, though, proved reluctant to support Kurdish identity demands, leading to the PKK’s birth.

Lebanon’s ethnic-Kurdish diaspora, journalist Aliza Marcus has shown, gave the PKK an introduction to Palestinian groups in 1976, allowing Öcalan to gain access to military training and arms. The Iraqi Kurdish leader Masood Barzani also granted the PKK access to his enclaves from 1982 onwards. The PKK succeeded in staging a series of successful attacks on Türkiye troops in the region, and also assassinated large numbers of ethnic Kurds and Turks who collaborated with the government.

Even though the PKK succeeded in establishing control over some ethnic Kurdish enclaves, time was not on its side. In 1991, the government of former President Halil Turgut Özal made efforts to end the conflict, lifting restrictions on the Kurdish language and opening talks with the PKK. This led the PKK to initiate the first of a series of ceasefires. The death of President Özal in 1993, though, saw the military resume its operations, this time using more fluid tactics that inflicted heavy losses on the insurgents.

Events over the next decades delivered a succession of blows to the PKK. In 1992, Türkiye invaded northern Iraq to flush out insurgents from the region. Türkiye and Syria signed an accord in 1998, ending the support Damascus had held out to the Kurdish insurgency. Öcalan was expelled from the country, and later held in Kenya with help from the CIA.

The incomplete endgame

To Türkiye’s elite, though, it was clear the war came with unacceptably high costs: In 1995, Marcus estimates, the country was spending $11 billion a year on a counter-insurgency campaign that tied down a quarter of its troops. The use of torture and other human rights abuses also retarded Türkiye’s push to become part of the European Union, leading business leaders to push the political establishment for a solution. Erdoğan’s rise to office as Prime Minister in 2003 saw him pursue conciliation with the Kurds, even offering a cautious apology for the crimes of Dersim.

From 2009 to 2013, secret talks between Erdoğan and the PKK explored the contours of a peace deal, negotiations that led the insurgents to announce the relocation of their combatants to northern Iraq. Like his predecessors, though, Erdoğan remained vague on precisely what he was willing to offer Kurdish regions.

Events soon overtook the negotiations, moreover, with new Kurdish mini-states rising in Iraq and Syria as they fell apart in the face of challenges from the Islamic State. The Türkiye-PKK talks disintegrated in 2015, with Erdoğan worried that the new Kurdish enclaves could pose an existential threat to his country.

Leaders of the PKK in Syria have already said a political solution will have to precede disarmament, not the other way around. And in Türkiye itself, there is no consensus on what a final political agreement with the Kurds might look like.

For more than a quarter century after Öcalan’s incarceration, peace has eluded both Türkiye and the Kurds. The complex story of the PKK insurgency holds valuable lessons for India, also mired for decades in many wars within. Among other things, the PKK’s failures demonstrate that robust nation-states can wear down even the most determined insurgencies, even those sustained by cross-border sanctuaries and support. The story also shows, however, that failure to engage the political foundations of insurgencies can squander those military gains.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. His X handle is @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)