In the Marathi play Trutiya Ratna, written by Jotirao Phule, two events stand out. First, both the husband and wife step out of their home to attend night school, pursuing their education at the institution founded by Savitribai Phule and Jotirao Phule. Second, the play, written in 1855, also depicts a scene in which husband and wife engage in a democratic discussion while sharing their food. This play challenges the traditions as well as the fractured-enlightened idea of modernity prevalent in the nineteenth century, based on the mimesis of Victorian morality. Both events mentioned in the play were deemed taboo. The “well-behaved” wife was expected to follow the husband’s diktats and be obedient. The play emphasises the concept of companionship between husband and wife in egalitarian terms, as opposed to the typical patriarchal understanding, where power is concentrated with the husband. This play was an offshoot of Satyashodhak’s (truth-seeker’s) thought process, which strives to empower women to question prevailing discourses and foreground their own sovereign perspectives. A reading of this play, for anybody familiar with the history of women’s education or Maharashtra, could guess that the companions in the play resemble the saga of Jotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule.

Institutionalising education

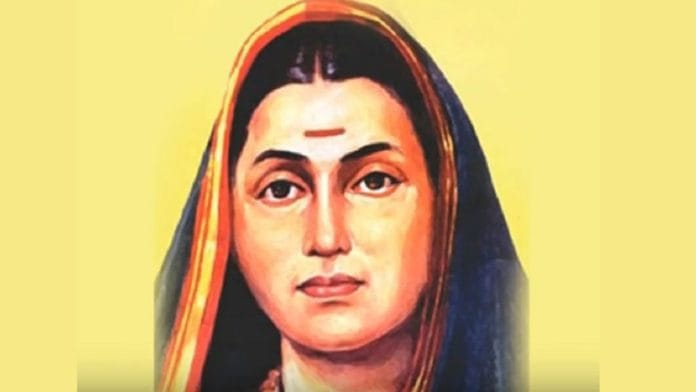

Savitribai Phule, the partner of Jotirao Phule, walked hand in hand with him, sometimes ahead, contributing to a new idea of peripheral, gendered modernity, i.e., Satyashodhak modernity (truth-seeking modernity), providing a firm base on which today’s superstructure of progressive Maharashtra rests. Savitribai was married to Jotirao at a young age. Thus, her education took place after her marriage, under the guidance of her partner, Jotirao.

Education became a liberating force for effecting radical and structural change in society, reclaiming humanity that had been lost. She believed education was a natural and fundamental human right, rather than a handout, and therefore helped Jotirao to open educational institutions that served the masses, especially women, shudras, and atishudras. Consequently, she can be called the pioneer of mass education in India, along with Jotirao, who strived for democratised and institutionalised education.

In 1848, the couple co-founded the “Native Female Schools.” The manifesto of this institution highlights the importance of education in women reclaiming their denied dignity and promoting self-development. To arrest the dropout rate among students, the school provided scholarships in the form of cash, also known as pagaar, to low-income students. These efforts were lauded by Marathi newspapers, such as Dnyanodaya, published from Ahmednagar, and the British Governor of Bombay, Lord Falkland. In 1851, at the demand of a girl who asked for a library in the school, the couple opened India’s first school library.

The effect of women’s institutionalised education can be traced in a letter published in the newspaper Poona Aalbarwar on 29 May 1852, where the anxiety of upper-caste males is starkly evident. This letter reluctantly acknowledges the Phules’ efforts in educating girls and fears that girls in Phule’s school would perform better than them in the upcoming exams, which would make caste-Hindu boys put their heads down in shame. Thus, the institutionalisation of education proved to be a game-changer for the marginalised gender-caste(s) strata of society. It provided them an avenue to empowerment, through knowledge and power, which had previously been restricted to only certain sections of society. Institutionalisation also ensured that these efforts were not person-centric; thus, this imparting of education would continue post the mortal lives of the couple.

Also read: Ambedkar incorporated various Western texts to develop a unique sense of labour in India

Reading Savitribai

Education as a cultural tool

“Awake, arise and educate

Smash traditions—liberate!”

The above lines were composed by Savitribai Phule. They challenged the culture of impunity perpetuated by dogmatic traditions, which created an asymmetrical power structure based on birth into a particular gender and caste. Women had little to no agency.

Savitribai was an ardent advocate of education as a tool for the emancipation of marginalised people, who were oppressed by the burden of orthodoxy, blind faith, and superstitions. Her subsequent compositions foregrounded a new culture of Satyashodhak Modernity, characterised by a scientific temper, employing the principles of rationality to question superstitions and challenge society to do the same. Using the medium of her writings, she culturally challenges the ritualistic dogmas, mocking them, using sarcasm in her writings, like,

“Kill the goats to fulfill the vows. I will fulfill my vows and give birth to a child.”

Savitribai stood with her commitment to educating women irrespective of the traditional patriarchal-casteist forces that deterred her efforts. Motivated by her Satyashodhak vision, she expressed compassion in the following words:

“My opponents’ narrow actions show that I am on the right path.”

For her, educating women was to make them understand and question these enmeshed patriarchal structures that hinder their creativity and disempower them. Her poem, Should They Be Called Humans?, lucidly puts forth the then-prevailing phallocentrism.

The woman from dawn to dusk doth labour.

The man lives off her toil, the freeloader

Even birds and beasts labour together

Should these idlers still be called humans?

The outcome of Savitri-Jotirao’s humanist educational efforts was radical women misfits like Mukta Salve, who belonged to the untouchable Matang community and was known for her pioneering essay, Regarding the Sufferings of Mahar-Matang; Tarabai Shinde, who authored Stree Purush Tulana, regarded as a pioneering work of organic Indian feminism; and later women like Tanubai Birje, who became India’s first woman news editor, and Savitribai Rode, who belonged to the Ramoshi community and contributed to the newspaper Ramoshi Samachar, putting forth the issues of Dalits, and many more. Thus, Savitribai’s efforts challenged the culture that perpetuated inequalities. Her poem, The Infection of the Outcaste(s), illustrates this:

For two thousand years, outcaste(s) have suffered this infection

of bonded labour, driven by the landlords into slavery.

In 1854, Savitribai Phule published her first collection of poems, titled Kavya Phule. She published Bavan Kashi Subodh Ratnakar, a collection of Marathi poetry, in 1892. Matoshri Savitribai Phulenchi Bhashane va Gaani, as well as her letters to Jotirao Phule, were also published. She edited four of Jotirao’s speeches on Indian history. Many of her compositions were found in Phule’s pioneering work, Slavery, published in 1873.

Also read: Amid caste clashes, it’s worth remembering Savitribai Phule on her birth anniversary

Challenging norms

The distinctiveness of her writing is evident in her compositions—women, shudras, and atishudras are at the center. Her radical poetry, which didn’t conform to the set patriarchal norms of those times, challenges the aesthetics of “modern” Marathi literature.

More importantly, during the time when education for women was taboo, Savitribai wrote and published, inverting the entire patriarchal textual tradition.

Her letters to Jotirao Phule addressed him by his first name, treating him as an equal partner. Her writings and poetry also highlight their beautiful, egalitarian relationship, based on shared commitments, shared visions, and mutual love, and respect for each other. The following lines sum up their comradeship.

Jotiba fills my life with joy.

As nectar does to a flower,

I am blessed with a renowned man.

My happiness knows no bounds…

Her writing presented an antithesis to the patriarchal thesis evident in nineteenth-century Marathi literary traditions, aiming to reimagine a new thesis based on the Satyashodhak Principles—equity and equality, seeking truth, rationality, inclusivity, and a scientific temper. This can be summed up in the lines from her poem, Man and Nature.

Let’s beautify human existence and make progress

Live and let live, get rid of all our fears and stress,

Human beings and all of creation are but two sides of a coin

To preserve these priceless bounties, let us join our hands.

Thus, Savitribai Phule, in the paradigm of thinking-doing, represents an energy that was inherited, imbibed, and transmitted to the women of India.

In the nineteenth century, in the normalised culture of bigotry, she presented a new synthesis of companionship with her partner, Jotirao Phule, to awaken and empower marginalised sections who accepted their state of derangement as fatalistic. They laid the foundations for the Bahujan enlightenment and empowerment, inspiring later generations, including BR Ambedkar and organic Indian feminists.

Aditi Narayani is an assistant professor of sociology at Lakshmibai College, Delhi University. She tweets @AditiNarayani. Nikhil Sanjay-Rekha Adsule, is a Senior Research Scholar at IIT-Delhi & John Dewey Emerging Scholar, USA. He tweets @beingkhilji. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)