Around a third of Indian households spend less on food per person than the government spends feeding a prisoner.

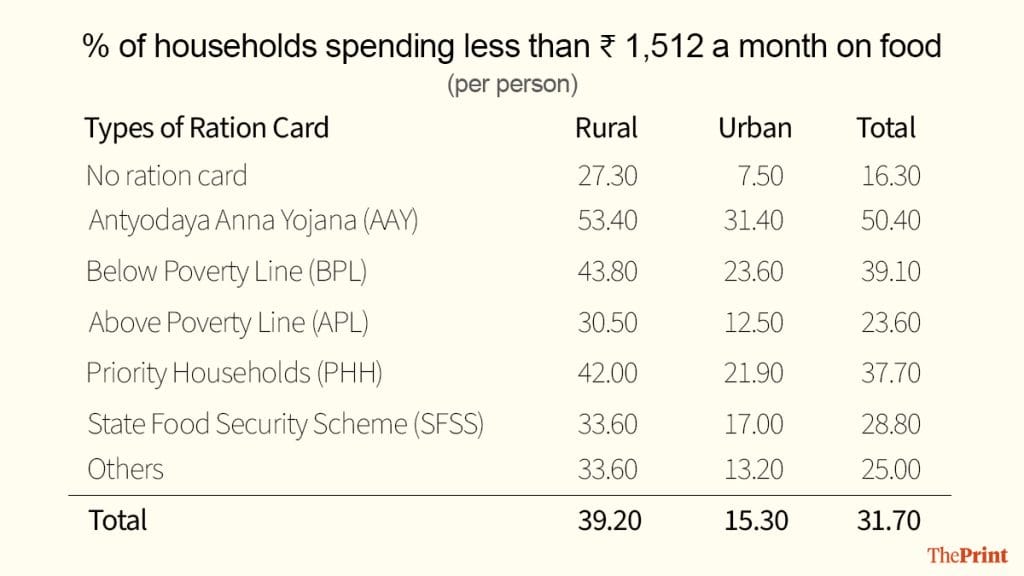

Data from the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2022–23 shows that approximately 32 per cent of households report monthly per capita food expenditure lower than Rs 1,512 per month. That’s the average amount the government spent monthly on food per prison inmate, according to a Lok Sabha reply by the Ministry of Home Affairs in 2021.

This comparison is not intended as a direct equivalence but serves to highlight the limited food spending capacity of a substantial proportion of households. It also raises important questions regarding the adequacy and nutritional quality of diets across different population segments. The 2022–23 HCES dataset is used as it ensures temporal consistency with other major recent surveys, such as the National Family Health Survey (NFHS, 2019–21). It also captures key post-COVID trends in evolving food expenditure patterns. While newer data (2023–24) may exist, the corresponding inmate food expenditure figures for that period are not yet publicly available.

Also Read: Why regular, updated dietary guidelines are important as non-communicable diseases rise in India

What the numbers show

The Rs 1,512 benchmark is derived from a parliamentary response indicating that in 2020–21, the government spent Rs 1,004.98 crore on food for 5,54,034 prison inmates. This amounts to approximately Rs 1,512 per inmate per month. When compared with household food spending captured by the HCES 2022-23, it is observed that roughly one-third of households fall below this threshold.

Importantly, this includes:

- Over 50 per cent of households covered under Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY), a scheme providing subsidised foodgrains to the poorest of the poor

- About 39 per cent under the Below Poverty Line (BPL) category.

It is important to note that these figures may be somewhat overestimated in terms of deprivation, as many of these households receive subsidised food through the Public Distribution System (PDS) or free food items from other sources.

The HCES methodology accounts for this by imputing the value of free food—estimating how much a household would have spent if those items were purchased at market prices. However, purchases made at discounted rates under PDS are not imputed in the same way, meaning that subsidised purchases can still result in low reported food expenditure—even when households receive sufficient quantities.

Also, PDS mostly covers only essential items such as rice, wheat, coarse grains, pulses, sugar, salt, and edible oil. It does not include nutritionally important foods like fruits, vegetables, dairy, eggs, and fish. These items are often costlier, and less expenditure on food suggests that for lower-income households, it is more difficult to access them.

Even if we ignore households receiving PDS benefits, it is noteworthy that nearly 24 per cent of Above Poverty Line (APL) households also reported monthly food spending below Rs 1,512, underscoring the broader issue of limited food expenditure across socio-economic categories. It can be seen that around 30 per cent of rural APL card holders are spending less on food compared to the government’s spending on prison inmates’ food.

Beyond quantity: What are households eating?

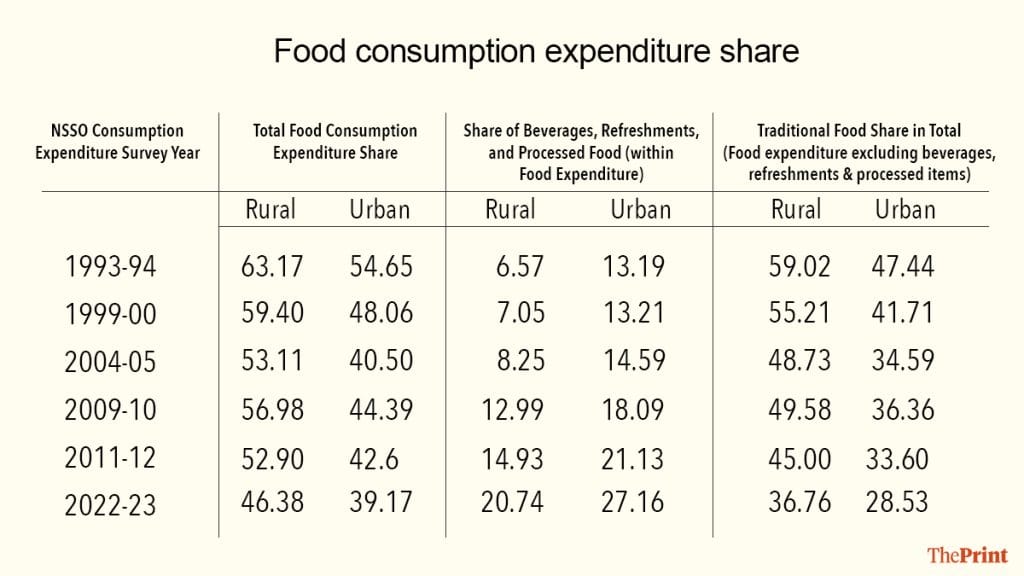

This pattern of low food expenditure reflects a broader, ongoing shift in household consumption. The share of food in total household spending has been steadily declining—in rural India, it dropped from 63 per cent in 1993 to 46 per cent in 2022.

But it’s not just this. The composition of food expenditure is also shifting in troubling ways. Spending on processed, packaged, and non-nutritive items is rising, even as spending on nutritious foods remains stagnant or falls.

Let’s look at the shift:

In urban India, more than one-fourth of the food budget now goes to beverages, snacks, and packaged items. In rural areas, that share has tripled over the past three decades. This processed food surge may be driven by convenience, aspiration, or aggressive marketing—but it may be displacing protein-rich, micronutrient-dense foods.

The hidden hunger line

India’s official poverty line has traditionally been linked to minimum caloric intake. However, current expenditure patterns point to a different concern. Not only are many households spending less on food overall, they are gravitating toward low-nutrition, processed items.

This shift is especially pronounced in the bottom deciles. For many households, chips replace fruits, sugary tea replaces milk, and biscuits substitute for meals. This is what some researchers call “status calories”—food chosen not for health, but for social image or convenience.

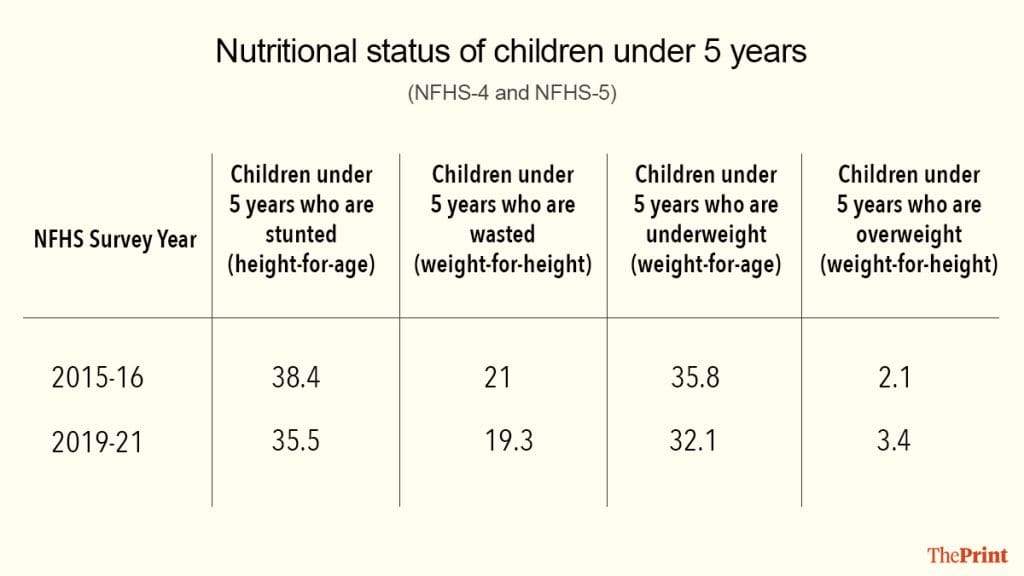

As a result, even if caloric needs may be met, dietary quality and nutritional adequacy remain compromised. This concern is reflected in persistent child health indicators. Despite some improvement between the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) rounds of 2015–16 and 2019–21, the decline in undernutrition among children under five has been limited, while the proportion of overweight children has risen from 2.1 to 3.4 per cent.

The table below highlights this trend:

Also Read: Food makes up less than half of an Indian household’s monthly bill, a first since Independence

Poor, but not in the old way

India’s progress in poverty reduction is well recognised. However, the HCES findings show that significant variations in food expenditure and nutritional quality persist across households.

Ensuring access not just to enough food, but to nutritionally adequate and diverse diets, remains a key development priority—particularly as consumption patterns evolve and new forms of food insecurity emerge, both within and beyond traditionally defined poverty groups.

The author is an assistant professor of Economics and Sustainability at the Institute of Management Technology, Ghaziabad. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

My school education didn’t teach me that sugar, biscuits, refined flour, deep-fried foods, desserts, ice creams, fruit juices, clarified butter, coconut, bakery products, and processed foods were bad for health.