Jaipur is nearly 300-years old and boasts of vibrant intangible culture and built heritage. It sees record tourist footfall almost every year and has become a must-visit destination. So, what more can a UNESCO Heritage tag do for the city? It already has the visibility, branding and tourism it needs.

The challenge in Jaipur is balancing heritage conservation with a growing city. For a city to be designated as world heritage under UNESCO, it has to fulfil certain criteria that makes it of ‘outstanding universal value’. It has to be an exceptional urban example in indigenous city planning and construction. Additionally, the city also needs to commit to protect and conserve its heritage.

Getting the tag

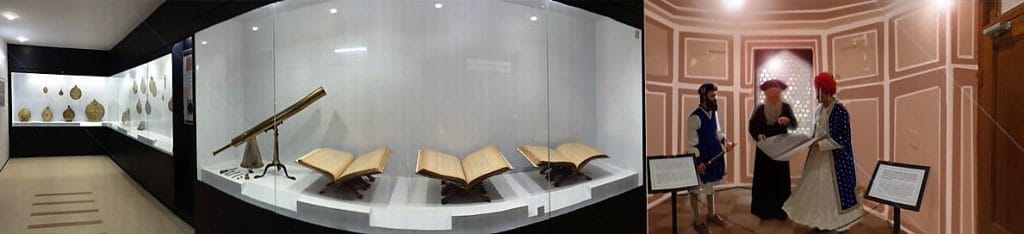

That’s where Dronah, my heritage preservation organisation, comes in. We have worked on getting UNESCO tags for Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, six hill forts of Rajasthan including Amber Fort and the UNESCO Creative City of Crafts and Folk Arts tag for Jaipur. My professional involvement in Jaipur’s urban conservation began in 2006 when Dronah was assigned to prepare the Heritage Management Plan for the city in association with Jaipur Virasat Foundation. This Management Plan listed various heritage assets of the city and Jaipur’s potential for global recognition as a whole. It had a listing of about 1,575 built heritage structures.

We placed Jaipur on UNESCO’s tentative list in 2015. A property has to be on the tentative list for minimum one year before it can be nominated for World Heritage. India has about 42 properties on the tentative list, and only one property per year can be nominated by a country as per UNESCO rules. So, it is a very competitive process and the evaluation itself takes one-and-a-half years after nomination. Jaipur city dossier was prepared and submitted in February 2018 when both the state and the Centre supported it as the candidate from India.

Also read: Jaipur makes its way to UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites

Struggles in urban conservation

Urban conservation is a long struggle. It often results in taking two steps forward and one step back. Multiple perspectives of the diverse stakeholders and periodic transfers of government officials plague each project. For instance, one of the more challenging works I can recall is the design for vendors’ stalls in the main Chaupars (bazaar squares) of Jaipur. Historically, these were the main public squares and had water bodies at the centre that were closed down with the advent of piped water supply in the 1870s. The process involved a tussle between the local vendors’ association and the mayor. The mayor finally decided to do away with the stalls due to protests by the permanent shopkeepers and the vendors ended up taking the stall designs from me so they could use it in a newly allocated area by the government. The learnings were that there is no single community voice and challenges of urban conservation lie in negotiations between stakeholders.

Another challenging issue was when the Jaipur Virasat Foundation tried to form a local residents’ welfare association for organising solid waste collection in the inner chowkris of Jaipur. The proposed president was threatened as this would jeopardise the regular workers’ jobs and nothing came of the entire effort.

The UNESCO inscription of Jantar Mantar in 2010, Amber Fort in 2013 and Jaipur’s recognition as UNESCO Creative City of Crafts and Folk Art in 2015 show why holistic conservation and not just restoration of buildings matters.

Jaipur on mission mode

The World Heritage tag will now add to Jaipur’s historic status – protecting it as well as giving it an official stamp. Since progress on Jaipur conservation works now requires periodic reporting to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, it places the ongoing planning, projects and commitments on a mission mode to be completed by December 2021.

It was extremely fulfilling when pending works such as architectural control guidelines for bazaars and Chowkri Modikhana designed by us in 2010 to retain the heritage character of each area got adopted by the municipal corporation in May 2019. We also got an order to take up the preparation of Special Area Heritage Plan for the Pink City on a priority basis while other experts were assigned to Heritage Impact Assessments. INTACH was to make the inventory as per conditions laid down by UNESCO.

Also read: Jai Singh wanted Jaipur to be a thriving commercial city, not military retreat of warlords

Smart, historic city

Jaipur was selected for Narendra Modi government’s Smart City Mission in 2015. Its Smart City plan continues to be guided by the heritage vision, proving that there need not be a conflict between urbanisation and conservation.

Jaipur has been an international destination since the 18th century when it was founded by Jai Singh II. European travellers and royal guests often visited Jaipur hearing stories of its grandeur. Giles Tillotson’s book Jaipur Nama records anecdotes of Indian and European travellers visiting this historic city.

The royal family of Jaipur, and later the government of Rajasthan, recognised Jaipur’s potential for heritage tourism. It was one of the first cities in India to have a heritage hotel – the Royal Rambagh Palace by mid-20th century. The people of Jaipur took particular pride in maintaining the city style. The shopkeepers in the bazaars continue to organise decoration competitions during festivals like Diwali. They vie with each other to maintain better facades and negotiate with government agencies to improve bazaar amenities.

Also read: Jaipur’s ‘smart voters’ complain the city is yet to catch up with them

The Heritage tag has triggered several initiatives for protection and conservation of Jaipur, as committed to UNESCO. But the utmost satisfaction comes when residents of the city call me personally to thank us for achieving this status for the city. They proudly say: “The world has truly realised the value of Jaipur”. It is the commitment that Jaipur residents have for their city that will finally safeguard its heritage.

Finally, the World Heritage tag is also an opportunity to sustain and celebrate Jaipur’s heritage. It is clear at the moment that neither the government nor the residents want to let go of this momentum.

The author is the founder director of DRONAH, an organisation working in the field of heritage. Views are personal.