In a country that prides itself as the pharmacy to the world, the word medicine should carry trust. But in Chhindwara, Madhya Pradesh, that trust curdled into grief, and then into national and international news headlines and page 1 stories. Over the past month, at least 21 children died in Madhya Pradesh, and three others in Rajasthan, mostly under the age of five, after consuming a cough syrup called Coldrif.

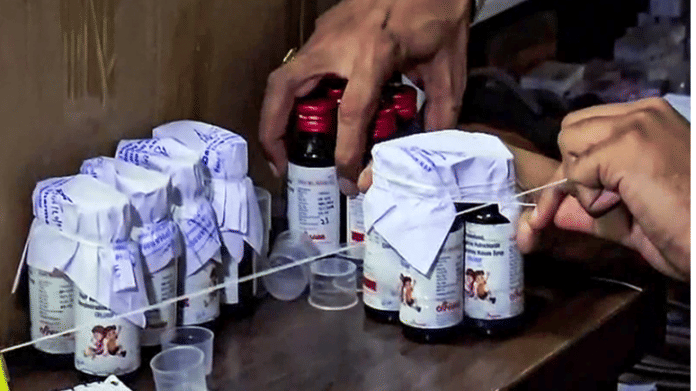

Manufactured under Sresan Pharmaceuticals, the syrup had been prescribed by doctors for years to treat cough and common cold in children.

But this isn’t the first time Indian–made syrup turned toxic. Between December 2019 and January 2020, 12 children died in Jammu and Kashmir after consuming a contaminated cough syrup. In Gambia, 66 children died in 2022 after drinking Indian–made syrup laced with diethylene glycol (DEG) and ethylene glycol. The following year, Uzbekistan and Indonesia reported dozens of similar deaths. Each time, the pattern repeated. The same “poison”, the same negligence, and the same slow official response.

The Coldrif deaths aren’t a tragedy. They are a reminder that behind every syrup bottle is a chain of responsibility, too often ignored. This collective apathy has exposed the nerves of India’s healthcare sector at multiple levels. And that is why Coldrif deaths are ThePrint’s Newsmaker of the Week.

It started with fever

What began as a few fever cases in Madhya Pradesh has spiralled into a national outrage over how easily spurious drugs slip through India’s regulatory cracks.

The tragedy’s epicentre lies in the state’s Parasiablock, a small cow belt with coal fields, surrounded by green hills, 30 km from Chhindwara city. Families live miles away from functional hospitals. Ambulances charge Rs 5,000-6,000 for a single ride to the district hospital—more than what people in the district earn in a week. Pharmacies have become the lifeline in emergencies, but now are shut due to panic. The panic of having their licence seized.

Four-year-old Usaid Khan loved reciting rhymes. When he fell ill with a fever in late August, his parents took him to Dr Praveen Soni’s local clinic. The doctor prescribed Coldrif, a syrup every parent recognised, trusted. Within days, Usaid’s body began to swell. He couldn’t pass urine. His parents rushed him to Chhindwara, and then to Nagpur. His kidneys had failed. His brain was swollen. Before dialysis on his tiny veins, he looked up at his mother and softly recited, “‘A’ se anaar ka meetha daana.” Hours later, he died.

Usaid wasn’t alone. Dozens of children in the nearby villages, many of them patients of the same doctor, had been given the same syrup. They showed identical symptoms. By the time health officials could step in, the deaths had multiplied. Tests conducted a month after the first reported death revealed that one batch of Coldrif syrup (SR-13), manufactured in Tamil Nadu, contained 48.6 per cent DEG. It is a chemical used in brake fluid and antifreeze, and its permissible limit in the syrup is 0.1 per cent.

Now, the factory owner, S Ranganathan, has been arrested by a Madhya Pradesh Special Investigation Team. The state government has suspended multiple officials, including drug inspectors, for negligence. But accountability stops short of where it should begin. The factory had cleared safety checks months earlier, and the nationwide call came only after children began dying.

Meanwhile, the president of the Indian Medical Association, Dr Dilip Bhanushali, has defended Dr Soni. “The real failure lies with the pharma companies and the government,” he said.

Madhya Pradesh chief minister Mohan Yadav has faced public fury after photos surfaced of him feeding sugarcane to elephants in Kaziranga, when the count was noting a sudden uptick. The Indian National Congress has been demanding accountability. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not yet commented on the tragedy.

Also read: Safdarjung Hospital says govt, not doctors, provides beds—after woman exposes chaos in wards

Dangerous normalisation of self-treatment

Despite global scrutiny, domestic oversight remains thin. India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation monitors more than 10,000 manufacturers, but it is chronically understaffed. State drug labs often lack the capacity to test ingredients and combinations promptly. Many small pharmaceutical companies cut costs by using industrial-grade solvents instead of pharmaceutical ones, assuming that the inspectors will look away and the paperwork will be easier.

A 2024 study found that nearly 64 per cent of Indians self-medicate, with the highest rates reported in North India. Cough and cold were among the most common elements treated without prescription, often using cough syrup and antipyretics bought directly from local chemists. The study noted that most people relied on pharmacists, old prescriptions, or family advice rather than doctors, citing financial constraints and limited access to healthcare. Researchers wrote that such widespread use of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs poses a serious risk of overdose, misdiagnosis, and toxicity.

A 2025 hospital–based community study conducted by JSS Medical College in Mysuru found that 46 per cent of parents treated children under five years of age using OTC drugs. Among them, 75 per cent used cough syrup, followed by antipyretics (72 per cent and antibiotics (58 per cent). The study noted that urban parents and homemakers were more likely to self-medicate than others. The researchers warned that this pattern of unsupervised OTC drug use, especially for very young children, reflects both gaps in healthcare access and a dangerous normalisation of self-treatment in India.

Also read: Herbal eggs are India’s new health fad. Bhopal entrepreneur adds tulsi, turmeric to feed

A dangerous irony

For families in Chhindwara and its neighbouring villages, the grief is inseparable from poverty and the following debt. Families spent everything they had, and borrowed more for hospital stays, doctor consultations. They sold jewellery and vehicles, only to be left with no answers. All they received was Rs 4 lakh from the state as compensation.

The Union health ministry has ordered risk-based inspections of pharmaceutical plants across six states, and has also banned multiple syrup brands, including Coldrif. But these measures are reactive, not preventive. It comes from the same cycle of denial and damage control. Tragedy after tragedy, the pattern stays the same.

India’s pharmaceutical sector is valued at $50 billion. It has built its reputation on affordability and accessibility. But the deaths in Chhindwara reveal a dangerous irony. India has been exporting life-saving drugs to multiple countries, while in its own towns, children are dying from medicines that have failed basic tests.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)