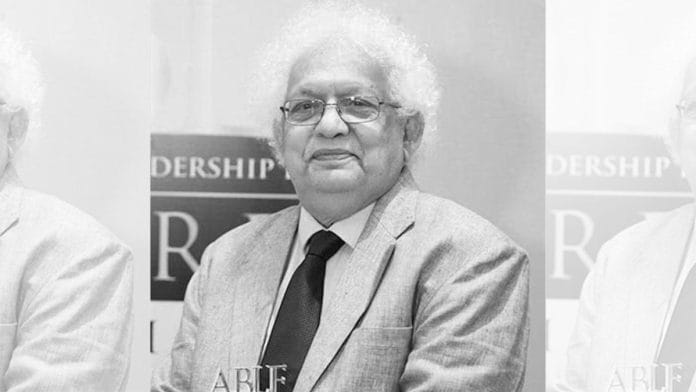

Lord Meghnad Desai carried his natural halo with grace and not a hint of pomposity. His untamed yet striking shock of white hair was a familiar sight to those of us who, as students, encountered him in the hallways of the London School of Economics. Though matters of state often kept him away—far more so than other faculty during my years there—when spotted in London, he invariably wore an impish smile and offered a wry remark on contemporary affairs, whether the evolving politics of Europe or the tumult of India.

On one occasion, as a classmate recalls, he was animatedly engrossed in conversation—his intellectual charm magnetically appealing—when he noticed an awestruck student lingering nearby. “Ah,” he muttered good-naturedly, “private affairs of public figures,” with the nonchalant air of a Peer of the Realm indulging in an innocent dalliance amid academia’s halls.

For Lord Desai, the pursuit of knowledge was a lifelong passion. Whether delving into Marxian economics, monetary policy, and economic history or celebrating Mughal-e-Azam, his works spanned disciplines with equal rigour, each contribution enduring in its relevance. Elevated as a Labour life peer in 1991, he never allowed party lines to contain his views. Known for his cross-party affiliations in the UK’s House of Lords, he regularly crossed swords—and built bridges—across ideological divides.

This refusal to be pigeonholed also extended to India. He advised successive governments, from Congress reformers to BJP-led regimes, bringing sharp intellect and empirical ballast to economic policy. Finance ministers and prime ministers alike valued his ability to question prevailing assumptions, often with evidence-laced humour.

Also read: PM Modi condoles demise of economist Meghnad Desai, hails his role in deepening India-UK ties

A master in every sense

Beneath the economist’s mantle lay a quieter passion: cinema. Beyond his academic stature, he took visible pride in his silver-screen debut—a cameo in the Sharmila Tagore and Soha Ali Khan film Life Goes On (2009)—a modern retelling of King Lear—alongside old friends Girish Karnad and Om Puri. Karnad and Desai were mates in college, and lore has it they once shared a stage in student dramas before making names in their respective fields.

Years after publishing Marx’s Revenge (2002)—a bold argument for Marx’s relevance in the era of globalisation—he was genuinely astonished when a classmate referenced its dense calculations. “You actually read it?” he asked in that characteristically self-deprecating tone.

He wore his erudition lightly, authoring incisive studies on India’s economic reforms while dispensing razor-sharp insights to anyone who sought them. As Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted in his tribute, Lord Desai was a regular commentator on reform, engaging with regulators and heads of state alike. His pithy observations often revealed their wisdom long after the moment had passed.

In his later years, spent largely in India, Lord Desai’s trenchant op-eds pierced even the high walls of North Block and the Prime Minister’s Office. Some mistook his critiques as quiet lobbying for official roles—a notion he laughed off when teased by former students like me. He remained generous with his time, mentoring young scholars, policy wonks, and the occasional disoriented LSE alumnus.

He was, in every sense, a master—an honorific he’d playfully redirect to me whenever I addressed him as “My Lord”. Globalisation and liberalisation were his intellectual playgrounds. He helmed the inaugural Chevening Fellowship on Globalisation, guiding India’s brightest minds to the LSE. A visionary institution-builder, he founded LSE’s Centre for the Study of Global Governance and its Development Studies programme, and had earlier co-created the Human Development Index with Amartya Sen and Mahbub ul Haq—a pathbreaking metric that looked beyond GDP to define progress.

To those who knew him closely, there was also a distinctly Bengali warmth—a side reserved for students and confidants. When my father passed away abruptly mid-term, Lord Desai sat me down upon my return and said, with gentle sagacity, “The grief will come in waves. Write through it, and you’ll finish your course.” It was advice as practical as it was profound.

Even in his eighties, he remained a prolific public intellectual. His columns in Indian newspapers sparked debate in Delhi drawing rooms as easily as in Westminster salons. He relished contrarian takes—not for performance, but because curiosity compelled him to probe every orthodoxy.

Today, that halo shines brighter still, as he ascends to higher realms, leaving behind admirers, friends, and a legacy that transcends borders. Lord Meghnad Desai belonged to no camp—and, somehow, to every camp at once. His life’s work, like his persona, was expansive, restless, and wholly original.

Dilip Cherian, India’s Image Guru, was a student of Lord Desai at the LSE. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)