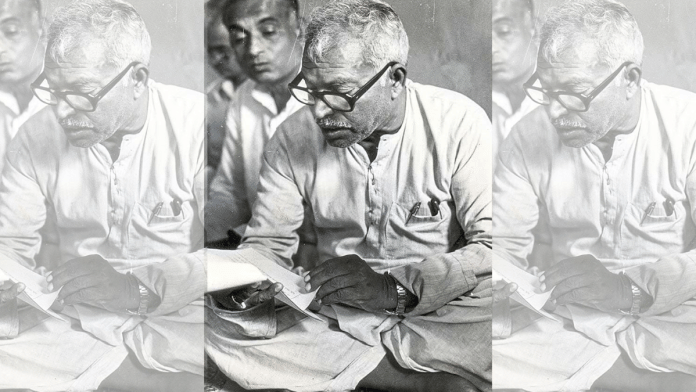

Karpoori Thakur (1921-1988) is remembered in Bihar and North India as a socialist leader whose actions and words were in perfect harmony. His simplicity and honesty earned respect even from his political adversaries. Unlike many in power who distance themselves from the public upon becoming ministers or chief ministers, Thakur was an exception, always amidst the people and known as a man of the people (Jananayak).

Thakur is credited with developing the idea of social justice that is now widely discussed across the country, particularly in North India. His significance is comparable to that of Periyar and Annadurai in South India, and akin to Ram Manohar Lohia in the north. Thakur, often referred to as the ‘Annadurai of North India’, played a vital role in bringing socialist politics and consciousness to a semi-feudal and backward state like Bihar, a formidable task he quite successfully undertook.

Born into a poor, backward barber caste, Thakur’s education was amidst hardships before he plunged into the freedom struggle. Bihar, his homeland, was a centre of various movements, including the peasant struggle led by Swami Sahajanand Saraswati and the Triveni Sangh (a coalition of three castes—Yadavs, Kurmis, and Kushwahas), and campaign for the emancipation of backward classes. The establishment of the Congress Socialist Party in 1934 in Patna, under Jayaprakash Narayan, and the Communist Party of India in 1939, naturally led Thakur, with his socialist mindset, to align with the freedom struggle focusing on socialist ideals.

After India’s independence, socialists parted ways with the Congress, and Thakur gradually became a prominent leader of the Socialist Party and movement. In the first general elections of 1952, he was elected from the Tajpur constituency in Samastipur to the Bihar assembly, likely the youngest member of the assembly then. Not only did Thakur demonstrate proficiency in parliamentary activities, but he also endeavoured to make the socialist movement popular and grounded.

The retirement of veteran socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan from active politics posed a significant challenge in keeping the movement alive in Bihar. While Lohia was experimenting with a small group, it was not gaining traction. Thakur was not aligned with Lohia. In 1964, a merger of Lohia’s Socialist Party and a faction of the Praja Socialist Party led by Thakur resulted in the formation of the United Socialist Party, known as Samyukta Socialist Party (Sansopa).

During this period, the party coined the slogan: ‘Sansopa ne baandhi gaanth, pichhda pavein sau mein saath’ (Sansopa has taken a pledge, ensuring sixty out of a hundred for the backward classes). This marked the adoption of a social justice agenda by socialist politics, heralding the dawn of a transformative era in the realm of socialist thought and action. Lohia and Thakur emerged as the luminaries of this movement, guiding it towards new horizons of inclusivity and equality.

Also read: Lalu, Nitish restricted Karpoori Thakur’s legacy. He was Bihar’s Ambedkar

In 1967, there was a political change in power dynamics in Bihar, along with eight other states in India. Thakur’s party emerged as the largest in the Bihar legislative assembly, but Thakur was not allowed to become the chief minister, through political manoeuvres. The leader of 63 MLAs became the deputy chief minister, while the leader of 27 MLAs became the chief minister. Despite these political intricacies, Thakur later served twice as the chief minister, always preferring the role of a socialist activist.

Thakur never clung to power and relinquished it whenever fundamental principles were at stake. His total tenure in government as chief minister was barely three to three and a half years. Others may have held power longer, but none left the imprint that Thakur did. He is remembered today for giving politics a new meaning and colour.

Whenever in power, Thakur used his influence for the benefit of the poor and downtrodden. He viewed politics through the perspective of farmers and laborers. Slogans like ‘Jab tak bhukha insan rahega, dharti par toofan rahega’ (As long as there is a hungry person, there will be a storm on earth) and ‘Kamane wala khayega, lootne wala jayega’ (The earner will eat, the looter will leave) were the slogans of the socialist movement. The goal was to centre politics around the subaltern and working class. Communists wanted the dictatorship of the proletariat, while socialists sought their democracy, particularly focusing on Dalits and backward castes.

Thakur remained committed to establishing democracy for these communities throughout his life. As deputy chief minister in 1967, overseeing the education department, he waived school fees, addressing the high dropout rates among poor children. His belief that progress could be achieved without mandatory English led to the abolition of its compulsory status, often misrepresented as ending English education altogether. His initiatives broadened education access and, during his brief tenure as chief minister in 1971, he abolished the land revenue from unprofitable holdings. In 1977, during his second term as chief minister, he implemented the recommendations of the Mungerilal Commission, advocating reservations for backward classes in government services.

These efforts marked the beginning of politics centred on social justice throughout North India. Although it led to his stepping down as chief minister, Thakur continued his fight, aiming to bring marginalised groups, including labourers, farmers, women, and others, into the mainstream. He always approached politics with thoughtfulness and empathy, encouraging sensitive politics. In 1977, as Chief Minister, he acknowledged that police had committed wrong in the custodial death of a sanitation worker, Thakaita Dom, and ensured justice was served, treating the case as if it were his own son. He in fact performed his last rites.

Thakur’s father was once insulted by the landlords of his village, but he stopped the district magistrate from taking action against them. He sought solutions to eradicate feudalism, demonstrating this to some extent. This is why the landlords of Bihar never forgave him. In the 1980s, when the Naxalite movement intensified in rural Bihar, a slogan emerged from the feudal powers: ‘Naxalbadi kahan se aayi, karpoori ki mai biaai’ (Where did Naxalism come from? Karpoori’s mother gave birth to it). Such abuses, which were in fact recognition by feudalists is not accorded to ordinary leaders; it requires a commitment to the poor.

No matter how much tribute is paid to Karpoori Thakur’s portraits and statues today, I know that no one will have the courage to walk in his footsteps. The recommendations of the Land Reforms Commission and the committee formed for the common school system have been ignored. Neither is anyone implementing them, nor is there any movement to do so. No one cares about the concerns of the poor and marginalized. In this melancholic atmosphere, memories of Karpoori Thakur come back with great force.

Prem Kumar Mani is a literary figure and thinker, and was a member of the Bihar Legislative Council. Views are personal.