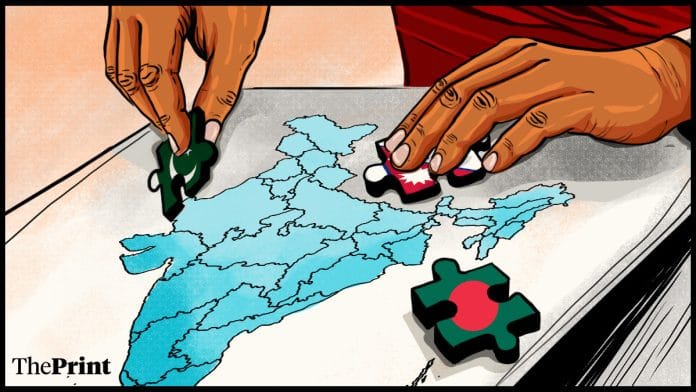

The global order is once again in a state of flux, overtaken by multiple crises that have shattered old convictions and exposed new vulnerabilities. In this altered landscape, India must urgently recalibrate its national security policy and defence architecture to meet the demands of a more volatile, multipolar world.

The wars in Gaza and Ukraine rage on with no clear end in sight, each serving as a proxy battlefield for deeper geopolitical rivalries, with the last round of Putin-Trump talks on Ukraine, held at Anchorage, Alaska, not making any significant breakthrough. Meanwhile, the US, the self-appointed global policeman, has turned inward and belligerent, unleashing a tariff war that has upended global trading norms and strained relations with erstwhile allies. India, caught squarely in the crosshairs of these upheavals, finds itself in a precarious position. Its principal adversary, China, has deepened its strategic partnership with Pakistan. The US, under the Trump administration, has grown openly hostile, with Pakistan Army Chief Asim Munir even issuing nuclear threats from American soil.

Compounding these challenges is the deterioration in US-India relations. President Trump’s tariff blitzkrieg of imposing duties of up to 50 per cent on Indian goods, has been vaguely justified on the grounds of India’s continued trade with Russia, particularly in oil and defence. However, there is a softening of the US stance on secondary sanctions related to oil imports after the talks at Anchorage. The irony is that the same administration which once hailed India as a counterweight to China now penalises it for pursuing strategic autonomy. The optics of Munir being hosted at the White House and issuing threats from Florida have not gone unnoticed by the strategic community in India, driving home a stark message that we can no longer rely on the US as a consistent strategic partner.

Also Read: India sees the value of US defence ties, but MAGA-style tariffs threaten long-term stability

India’s strategic pillars under strain

India’s strategic calculus is based on a few pillars: a robust deterrent posture against China and Pakistan; a growing partnership with the United States; and a commitment to multilateralism through forums like the UN, SCO, and BRICS. But each of these pillars is now under strain.

China’s aggression along the Line of Actual Control, its naval assertiveness in the Indian Ocean, and its deepening ties with Pakistan—manifested in joint military exercises, intelligence sharing, and infrastructure projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor—pose a multi-dimensional threat. Pakistan, emboldened by Chinese backing and the militarisation of its polity, has escalated both its rhetoric and capabilities. Munir’s recent threats to target Indian economic assets such as the Jamnagar refinery and other intemperate remarks on nuclear retaliation while on US soil mark a dangerous new phase in Pakistan’s strategic signalling.

Compounding these challenges is the deterioration in US-India relations. President Trump’s tariff blitzkrieg of imposing duties of up to 50 per cent on Indian goods, has been vaguely justified on the grounds of India’s continued trade with Russia, particularly in oil and defence. The irony is that the same administration which once hailed India as a counterweight to China now penalises it for pursuing strategic autonomy. The optics of Munir being hosted at the White House and issuing threats from Florida have not gone unnoticed by the strategic community in India, driving home a stark message that we can no longer rely on the US as a consistent strategic partner.

Overhauling national security doctrine

In light of these developments, India must undertake a comprehensive overhaul of its national security doctrine.

In light of these developments, India must undertake a comprehensive overhaul of its national security doctrine.

First, it must embrace the reality of a multipolar world and diversify its strategic partnerships. While the Quad remains important, India must also deepen ties with middle powers like France, Japan, and Australia, and explore new alignments with ASEAN, Africa, and Latin America. A new ‘Quad’, comprising Australia, Japan, and India, and including other countries of the South China Sea littoral—most notably the Philippines, which has shown the gumption to stand up to Chinese bullying in the region—must be explored. In this period of uncertainty, it is very unlikely that the Quad summit scheduled to be held in India later this year will materialise. Attempts should also be made to resuscitate SAARC, a fitting platform to engage our immediate neighbours. The aim should be to build a web of relationships that reduces dependence on any single power and enhances India’s leverage in global and regional forums.

Second, India must accelerate its defence modernisation. The recent success of the S-400 air defence system in intercepting Pakistani aircraft during Operation Sindoor underscores the importance of technological superiority. India’s nuclear triad, bolstered by MIRV-capable Agni-V missiles, provides credible deterrence, but conventional capabilities must also be upgraded. Investments in cyber warfare, space-based surveillance, and unmanned systems are no longer optional but inescapable operational imperatives. The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) must be restructured to incentivise innovation, concentrating solely on R&D and moving away from production. Reduction in procurement timelines remains a constant priority.

Third, India must rethink its internal security architecture. The threat from cross-border terrorism remains acute, especially with Pakistan’s military increasingly aligned with extremist groups. The menace from Left Wing Extremism, though reduced, retains the potential to destabilise the country internally. Intelligence coordination between central and state agencies must be streamlined, and counterterrorism capabilities enhanced. The Paramilitary Forces (PMF), which play a crucial role in border management and internal security, must receive sounder training, modern equipment, and be better integrated with the armed forces. Attachment of PMF officers with army units would go a long way in achieving the dual aim of training and integration. The absorption of released Agniveers into the PMF will also be a positive step.

Fourth, India must recalibrate its nuclear posture. While maintaining a no-first-use policy, it must signal readiness to respond decisively to any nuclear blackmail. This includes developing second-strike capabilities, securing command and control systems, and conducting periodic strategic reviews. The rhetoric from Pakistan’s leadership, threatening to “take half the world down,” must be met not with escalation but with clarity and resolve. Re-articulating our nuclear policy, especially with regard to ‘launch on warning’, will discourage any nuclear adventurism. Strategic maturity lies in enunciating red lines and indicating the will to respond should these be in danger of being breached.

Fifth, India must leverage its economic position as the world’s fourth-largest economy as a strategic tool. The asymmetry between India and Pakistan is most pronounced in economic terms. Every percentage point of GDP growth widens the gap, reducing Pakistan’s relevance in global forums. India must continue to liberalise its economy, attract foreign investment, and build infrastructure corridors that enhance connectivity and resilience. Initiatives like the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) need to be fast-tracked. Pending trade agreements, especially with ASEAN, should be pursued and, where existing, implemented without further ado. A multipolar export strategy must be adopted to mitigate the impact of US tariffs. The US may be our largest trading partner, but it is certainly not the only one, with the rest of the world still accounting for around 70 per cent of our trade.

Also Read: What India can learn from Israel about atmanirbharta in defence

Taking control of the narrative

Finally, India must invest in strategic communication.

In an age of information warfare, perception shapes policy. India must counter hostile narratives and, by engaging with global media, think tanks, and diaspora communities, actively project its role as a net-security provider for a stable and inclusive Indo-Pacific. The goal should be to build a narrative of India as a responsible power that’s firm in its resolve, mature in its conduct, and committed to resolving disputes through dialogue.

The world is not what it was, and India cannot afford to be complacent. The threats are real and evolving, alliances uncertain and dynamic, and the risks higher than ever.

But within this churn—a modern-day Samudra Manthan—lies the opportunity for India to rise and redefine its role on the world stage by building a security architecture that is robust and adaptive.

India must chart its own course, guided not by fear but by foresight. The recalibration must begin now, sans rhetoric, but demonstrating firm resolve.

General Manoj Mukund Naravane PVSM AVSM SM VSM is a retired Indian Army General who served as the 28th Chief of the Army Staff. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

The conclusion that USA is turning against India is a hasty. Specially when Trump is the President. Mr. Trump appears inconsistent on short term but is very very consistent on long term ( According to a Russian strategic expert. ). And those who go through his record since 1980s tend to agree.