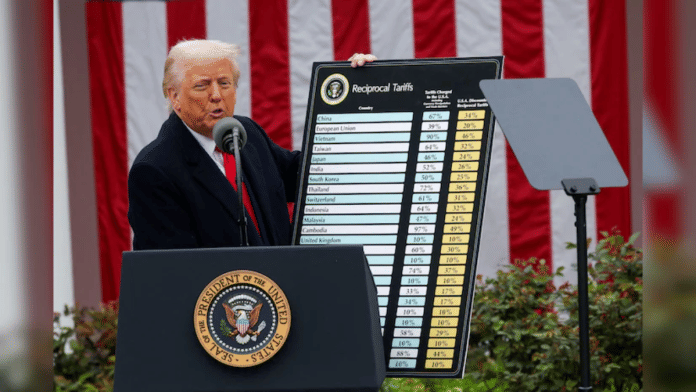

At a time when active negotiations to secure the US-India Bilateral Trade Agreement or BTA are underway, the US’ decision to impose a 25 per cent tariff on Indian goods starting 1 August is surely not good news for the Indian economy and business sentiments. India’s exports of automotive components, pharmaceuticals, marine products, apparel, gems and jewellery, chemicals, oilseeds and leather goods are expected to be worst affected due to this levy.

The unfavourable announcement is likely to pose headwinds for India’s GDP growth. The US has simultaneously pushed the boundaries of trade negotiations towards strongarming India to comply with its stance on the war in Ukraine by levying a yet-unspecified penalty for India continuing to purchase Russian oil and defence equipment. A 25 per cent tariff will leave India worse-off against its immediate competitors until a new deal is struck. Rather than retaliating unwisely to these pressure tactics, India must do whatever it takes to fast-track the BTA negotiations.

Undoubtedly, India has posed one of the highest import tariffs worldwide across many products, and maintained daunting non-tariff barriers. This is unsustainable for its globally integrated economy. Analysts have feared that Prime Minister Modi’s Make in India mission signals India’s return to higher tariffs. However, the lowering of import tariffs is an inevitable shift, despite some key Indian industry leaders seeking to rely on the callipers of high import duties. The Make in India mission can only benefit from riding on the wave of enhanced manufacturing competitiveness amidst an environment of lower regulatory cholesterol and a much higher ease of doing business. Business groups batting for protectionism will predictably register their discomfort but would eventually relent to lower import tariffs as the new rules of engagement. India must allow this pragmatic realisation to spur the next round of trade negotiations with the US.

US-India BTA

As is well known, the major roadblock has been over tariffs for US agricultural commodities and dairy products exports to India. Washington has been pushing for greater access to India’s agriculture sector, viewing this untapped market as a huge opportunity. New Delhi has been resisting this expectation due to its domestic sticking points over food security and securing the interests of hundreds of millions of small and marginal farmers earning below subsistence levels of income. The apprehension of hurting the sentiments and interests of small Indian farmers is not an imaginary fear but a serious political reality.

The Indian government has been reluctant to overlook these concerns, particularly after the domestic backlash to its efforts to liberalize the agriculture sector through three Farm Bills which were repealed following large-scale farmers’ protests in 2020-21. Compounding India’s concerns is the issue of genetically modified (GM) crops which has led to resistance to the lowering of tariffs on American GM produce like maize and soya. India does not allow such products due to the perceived health risks for its 1.4 billion-strong population. The US needs to appreciate that India has very limited elbow room to bend significantly on these issues.

A key feature of India’s economic history this decade has been its growing willingness to enter into free trade agreements (FTAs) and preferential trade agreements with major Western economies. Following the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) in 2022, and the U.K.-India Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) in 2025, India is already negotiating an FTA with the European Union. With a recent thaw in the frosty diplomatic relations of the last two years, India has also resumed negotiations for an FTA with Canada, which had been suspended since 2023.

The most notable of these efforts to open its doors to the West is the US-India BTA, which had already concluded its fifth round of negotiations. A full-blown BTA intends to improve mutual market access, reduce tariff barriers, remove non-tariff barriers, expand consumer benefits, and improve the integration of supply chains. Despite the fact that some irritants still remain and the US has already announced a 25 per cent tariff and a penalty on Indian exports, the US and India need to expedite discussions leading to an interim trade deal, pending a full-blown BTA.

Also read: Modi’s ‘Make in India’—a case study in what happens when strategy is replaced by storytelling

Win-win trade deal

The post-pandemic world has been contemplating a partial relocation part of its manufacturing supply chains to destinations other than China. India is a major prospect on this front as an alternate manufacturing destination. While trying to capitalize such opportunities, India has tasted limited success as not very many supply chain shifts to India have actually occurred so far. A win-win trade deal between the US and India would bring more FDI especially from the US into India, create more jobs, provide both nations better access to raw material and capital goods, and improve the competitiveness of Indian manufacturing. Such a scenario would surely pave the way for India’s emergence as a viable alternative to China in the global exports market.

The US’ total goods trade with India in 2024 was USD 129 billion out of which the US goods exports to India were USD 42 billion (up 3.4 per cent vis-à-vis 2023) and US goods imports from India were USD 87 billion (up 4.5 per cent vis-à-vis 2023). India has a large trade deficit with its largest trading partner China, but enjoys a goods trade surplus with the US of around USD 46 billion in 2024. Prime Minister Modi and President Trump have set an ambitious target of doubling bilateral trade to USD 500 billion by 2030. In most countries, international trade represents a significant share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). India’s trade to GDP ratio was reported at 44.67 per cent in 2024, according to the World Bank. The impending US-India trade deal offers India a major opportunity to further boost its trade-to-GDP ratio which is generally considered a healthy indicator for any economy.

India has already emerged as the world’s fourth largest economy having equalled the GDP of Japan. It is also the fastest growing economy among major countries. With a long history of non-alignment and strategic independence in its trade policy, India has largely shielded itself from international pressure. With the high approval ratings of the BJP-led regime and its strong nationalistic overtures, there is unlikely to be any significant domestic perception of India being bullied by the US and therefore, this is unlikely to affect the impending trade deal with the US.

Win-win negotiations are always about give and take, a deft combination of assertion and acquiescence. A mutually acceptable trade deal would do a lot of good to both countries. It will be a shot in the arm for India. Once in the bag, the EU-India trade deal will be finalised in due course of time. These deals would mean a significant liberalization of India’s trade regime ensuring far more open markets with two major Western economies.

As long as these deals do not rock the boat for the Indian agriculture and dairy sectors, they will also find traction amongst its constituency of middle-class voters for whom Western markets are aspirational. For any future FDI, India would emerge a very lucrative destination as border roadblocks would reduce. The US stands to gain by way of greater access to Indian markets and the emergence of India as a viable manufacturing destination. Avoiding laying most of its eggs in the Chinese basket will also be consistent with the US’s strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific.

Though President Trump’s announcement of a 25 per cent tariff may seem a setback in the short-run, India’s national interest lies in treating this as an opportunity to urgently seal, at the very least, an interim trade deal with the US for immediate relief. This will provide legroom to iron out India’s domestic concerns, de-link trade negotiations with its long-standing ties with Russia, and arrive at a sustainable long-term free trade agreement with the US down the line.

Jayant Krishna is a senior fellow (non-resident) with the Chair on India and Emerging Asia Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, and an adjunct professor of business negotiation at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Lucknow.

Ujjwal Krishna is an academic fellow with the Australia India Institute at the University of Melbourne, an adjunct research fellow with the Centre for Human Security and Social Change at La Trobe University, and a consultant at The Asia Foundation’s Regional Governance Unit.

Views are personal.