When we first started studying Indian crops and creating their balance sheets some years ago, we learned two important things. First, no one knew how much crops were consumed in the country, and second, what their stock levels were at any point in time. Even for crops with a high degree of government intervention — via institutions such as the Food Corporation of India and NAFED — an accurate estimate of the national stock was nearly impossible to get.

So, at any point in time, these two key elements of a crop’s balance sheet are only, at best, guesstimates or some extrapolated numbers created from the decade-old National Sample Survey Office’s (NSSO) monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE) estimates. This makes policymakers, traders, and even researchers like us fret every time prices don’t follow a projected trajectory.

Interestingly, even though we acknowledge our ignorance about the national levels of stocks and consumption, the only variable we blame for any projection error is the central government’s crop production estimates. Invariably, when prices for tur or even wheat or rice went up to high sticky levels recently, the blame was squarely put on the government’s production estimate. Many, including one of the authors, blamed the government numbers multiple times.

It is not that the blame is completely unfounded, but we need to also acknowledge that many variables in a crop’s balance sheet, including the level of consumption, are only guesstimates and errors could arise from any front. Having worked closely with the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) in the past year, we briefly outline how the department is working toward bettering these production estimates.

But first, the context.

Also read: Assembly polls did what farmers’ protests couldn’t—Swaminathan formula MSP for paddy & wheat

The root issue

Let us take an example of wheat in FY22-23. As per the MoA’s second advance estimate released in February 2023, against the target of 112 million metric tonnes (MMTs), the actual crop was predicted to be about 112.2 MMTs. In a year when wheat yields were predicted to have suffered on account of February/March heatwave and hailstorms, this government estimate was a pleasant surprise for many.

That month, the consumer price index (CPI) for wheat showed 25 per cent annual inflation. This rate was 20 per cent even in March 2023. In May, the government released its third advance estimate, pegging the wheat crop at 112.7 MMTs, marginally higher than the previous estimate. CPI wheat annual inflation rates continued to stay in double digits. Then came the government’s May 13 decision to ban wheat exports. Later in October 2023, the Centre released its final estimates, which fixed Indian wheat for FY22-23 downward by 2 MMTs to 110.6 MMTs.

Among other things, this highlights two important issues. First, for a crop sown in October 2022, one had to wait for 12 months to get a robust estimate. And second, this has associated risks for policymakers and traders who have to rely on inaccurate data in the interim for making critical decisions.

In addition to these estimates, the government is also focusing on improving the overall agricultural infrastructure to support farmers and enhance productivity.

Also read: Poultry and chicken keep food inflation low. Time India’s policymakers promoted it

Evolution of MoA’s collection and reporting

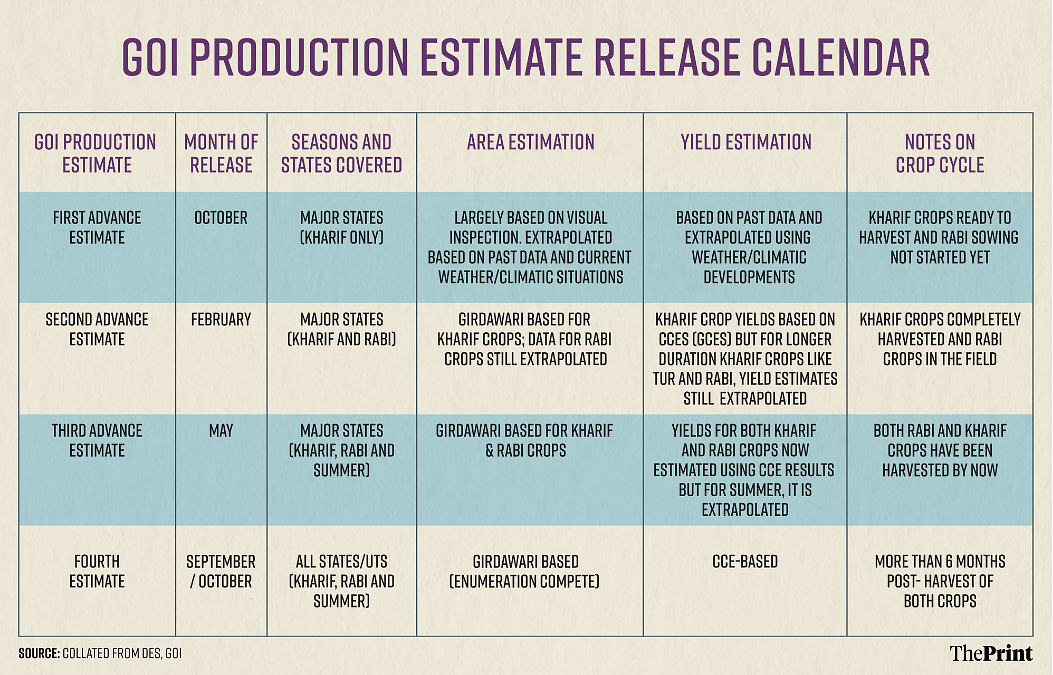

MoA tracks and predicts crop yields and studies acreages to arrive at a crop’s production estimate. For any agricultural year (July-June), the ministry releases production estimates for its key agri-crops four times (Table 1). Its first advance estimate (FAE) is released in October and the fourth or final estimate of the crop comes by the next October.

As agriculture is a state subject, MoA depends on states for receiving field data on yields and acreages. Upon receiving the data, it collates and cleans it to obtain national-level estimates. Delays in submission of data by states hold up collation by MoA. Most of these delays happen due to logistical, technological, and even administrative reasons.

The new method

In light of the above challenges and to leverage opportunities unleashed by the digital drive, MoA has undertaken fundamental changes in its data collation, cleaning, and processing protocols.

The Digital Crop Survey (DCS) is one of them. Under DCS, states have been asked to report real-time GIS-GPS tagged field data directly to MoA via an API. This is equivalent to conducting a digital girdawari (document with the land revenue department that specifies land and crops details). Among other things, this would serve two purposes. First, access to real-time data will bypass administrative and logistical delays. And second, with GPS tagging, data verification will be swifter and more credible. The DCS was piloted in 11 states during kharif 2023 and is proposed to be rolled out across the country from kharif 2024.

The method of crop cutting experiments (CCEs) is also being revised. Approximately 8.5 lakh CCEs are conducted annually in the country. MoA has now developed a mobile app to collect geotagged data under CCE too. The CCE results from Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), though would be used for triangulation, are planned to be kept separate. CCEs done exclusively for estimating yields under the General Crop Estimation Survey (GCES) are to be used by states for estimating yields. This, too, was piloted the same way as DCS and will go national in 2024.

To make their assessments more robust, MoA is also designing ways to validate and triangulate the field data. In collaboration with ISRO, it is utilising satellite data to validate area and yield assessments. Its Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast Centre (MNCFC) continues to use remote sensing through satellite imagery, coupled with ground-based data and spatial mapping tools, to provide data on area production yield (APY) at the subnational level for major crops.

Way forward

One needs an eye in the sky and boots on the ground, and MoA is endeavouring to firm both. When these new initiatives become fully operational at the national level, India is likely to receive robust, near-real-time production estimates. Timely access to credible data is basic to any policymaker or trade, and these steps by MoA are bound to bring much-needed agility into the system.

Saini is CEO, Arcus Policy Research and Jain is Assistant Director, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)