When political rhetoric and history revisionism projects around the world are focussing on divisions and cultural silos, museums have a profound role to play. Think of the museum institution as a public intellectual. It has an intellectual duty to remind people about civilisational connectedness amid all the ‘clash of civilisations’ talk. To that end, museums are a global public good in turbulent times.

A museum is a safe place for unsafe ideas, I learned many years ago. Today, migration is the unsafest idea. The Humayun’s Tomb museum’s new exhibition called ‘Shared Stories: An Art Journey Across Civilisations Beyond Boundaries’ wades into this unsafe territory.

Curated by the Italian archaeologist Laura Giuliano, the exhibition, which will be on display until May, brings together the entangled histories of India, Pakistan, China, Afghanistan, Iran and Italy — with 120 artefacts loaned to India by Rome’s Museo delle Civiltà (or Museum of Civilisations).

The exhibition reminds us that ideas were the original migrants.

Also read: Italian museum brings Afghan Buddhist artefacts to India—it’s a symbol of shared history

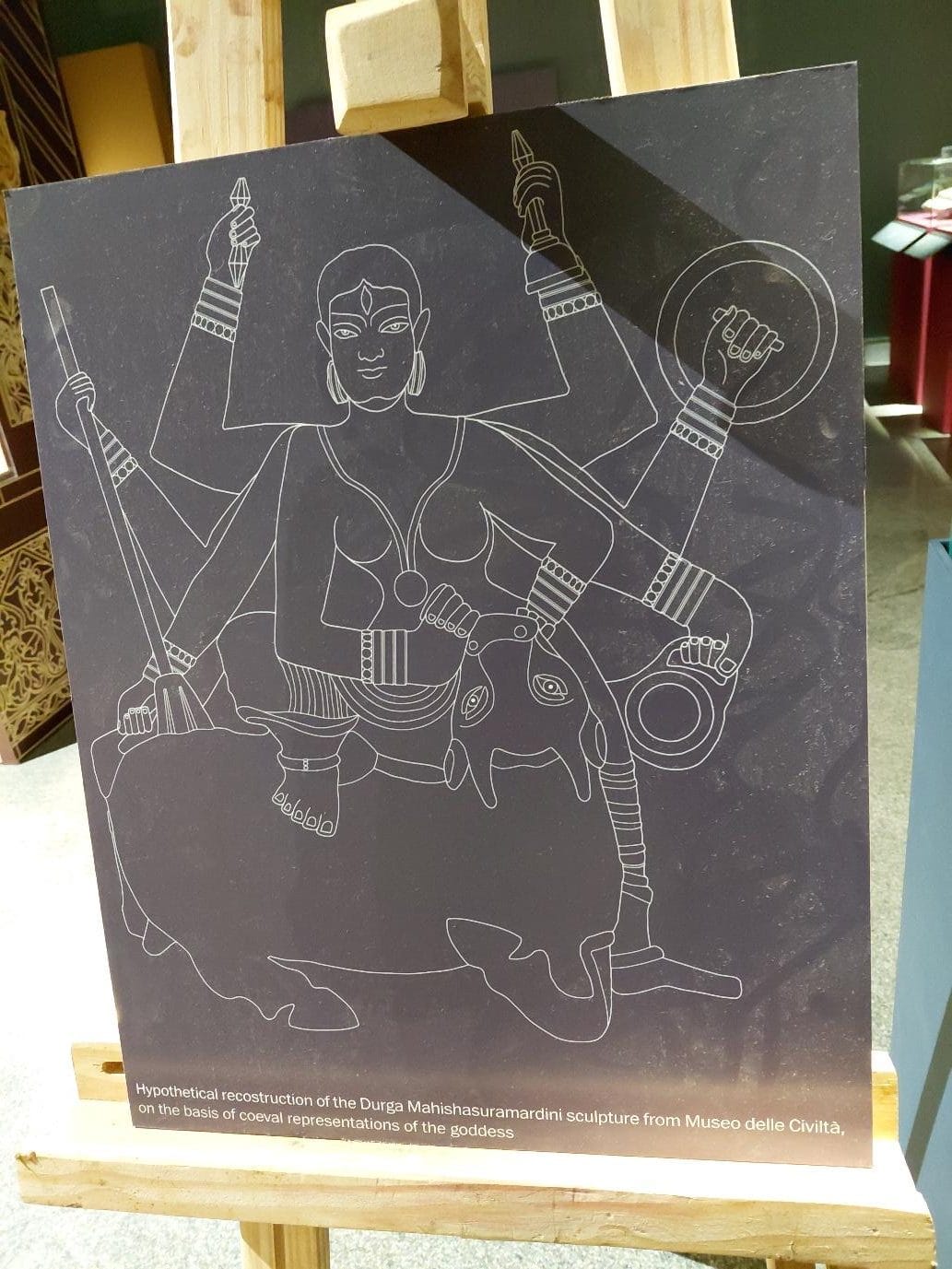

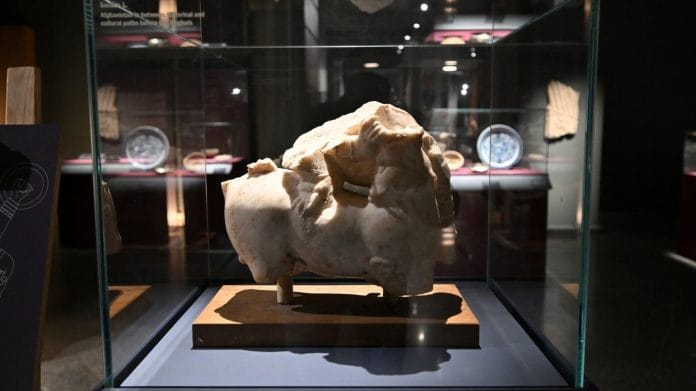

Durga in Afghanistan

Any conversation about modern-day Afghanistan throws up images of war, Taliban, women under Sharia law. Durga isn’t what comes to mind. But the Shared Stories exhibition in New Delhi opens with this. It offers a fragment of Mahishasura Mardini (the slayer of the asura Mahisha) as its central, blockbuster artefact. It was found in Afghanistan in the 7th century CE Shahi period. The magnificent marble statue is broken but what is visible is how she holds the bull’s horn by one hand, the folds of her sari and her seat on the animal. The object is called ‘Durga slaying the buffalo demon’.

The artefact’s centrality and foregrounding are a curatorial signal, meant to produce a sort of cognitive dissonance. That is the power of art history curation in museums. It can reveal hidden patterns and simultaneity of cultures in a non-preachy way.

Most of us study history in a linear fashion. I prefer to engage with history as if time and earth were flat. What was going on across different continents in a single century? Where did the movements against religious orthodoxy occur and when? It is my lateral entry into the past.

The Humayun’s Tomb exhibition does exactly that. It looks for shared artistic motifs that recur repeatedly in material culture found in different civilisations. Ideas and cultures moved as well, not just people.

Also read: What’s missing in the new Humayun Museum of Mughal history? A key decade of India

Living forms in Islamic art: Always forbidden?

Our conventional understanding says that Islamic art rarely portrays living forms such as human beings or animals in its carvings. And when we do find them in many Mughal and pre-Mughal Islamic monuments in India, we conclude that it’s a sign these monuments have been built on the demolished debris of Hindu temples. The presence of animals and birds is thus evidence of invasion and demolitions for us.

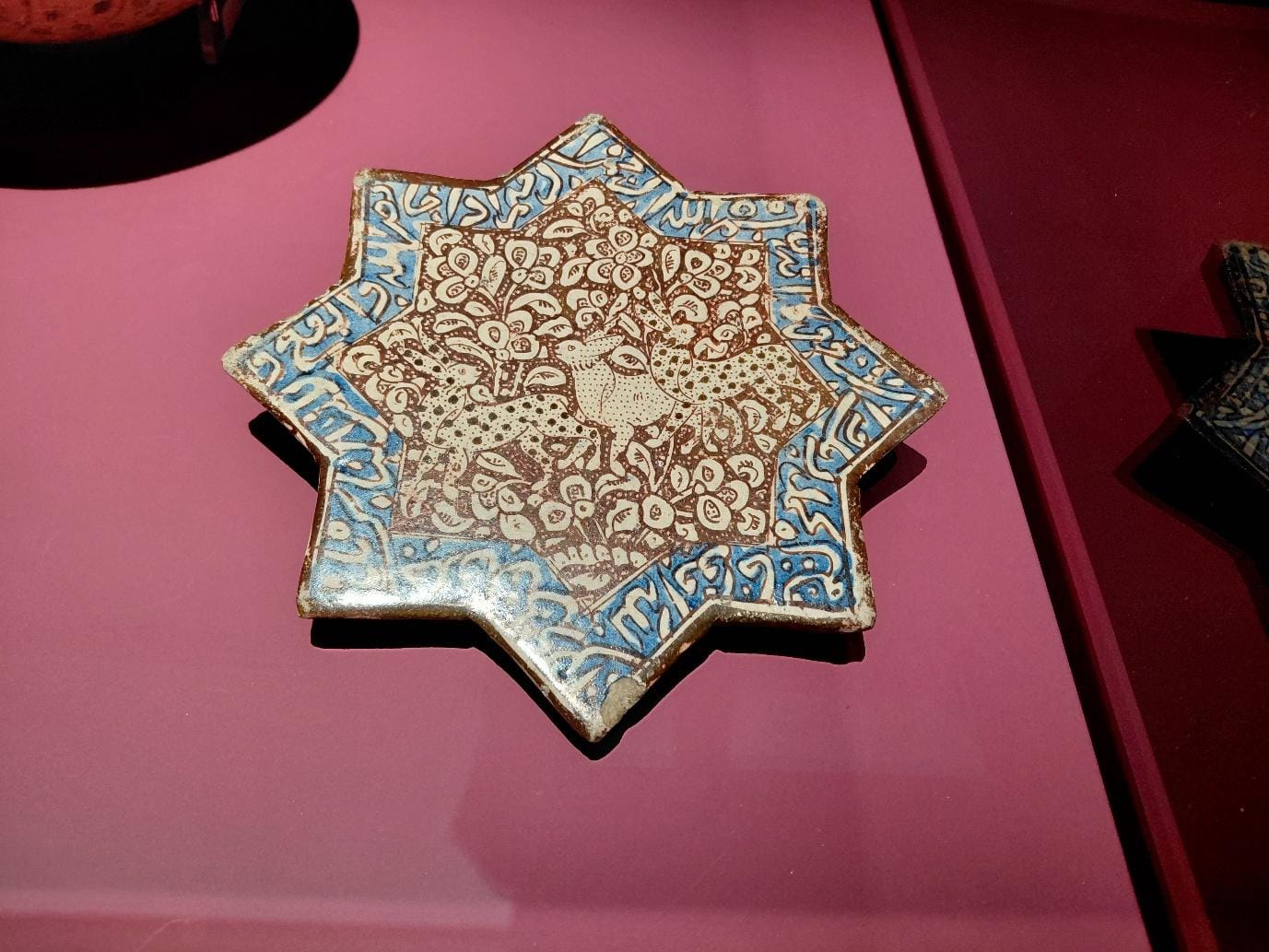

But here’s a curious fact. The exhibition has several artefacts from Iran, Afghanistan and Swat (in Pakistan) that sport Quranic calligraphy along with birds and animals.

Life forms are portrayed alongside Islamic verses in the fragment of a pilaster from the Ghaznavide palace in Ghazni, Afghanistan (late 11th and early 12th century CE). These display the long overhang of rich pre-Islamic Persian heritage. Excavations at Ghazni show a remarkable continuity of settlement, carrying Hindu, Buddhist and Islamic ideas, and marking the region as a complex cultural crossroads of India, Iran, and Central Asia.

Similar motifs appear elsewhere: inscriptions with bird figures and vegetal scrolls on tiles from Kashan, Iran (Ilkhanid period, 1256-1335), and a dish with ducks and nakshi script inscriptions from Kashan dating to the early 13th century.

Clearly, there was a cultural overlap of artistic traditions from the pre-Islamic era into the Middle Ages. At what stage point in Islam’s growth did this become an anomaly and forbidden?

Also read: Madras artists were latecomers to Indian modern art. A Bengal painter & a critic pushed them

Kissing birds and a connected medieval world

A frequently recurring motif across geography and time is a pair of intertwined, kissing birds.

The exhibition notes that the image circulated during the Middle Ages along the Inner Asian routes and into the Islamic world, carried by nomadic peoples. The motif is found in architecture, ceramics and funerary objects, across Iran, Egypt and Europe. Most notable is this line from the exhibition: “Through the mediation of Islamic art, the entwined kissing birds motif travelled to medieval European art.”

A water basin from Ghazni, Afghanistan (second half of the 11th century); a spoon-fork decorated with entangled peacocks and a Kufic inscription from Ghazni (12th century); bowls with kissing and marsh birds from Nishapur, Iran (10th century and 810-999); and a marble funerary urn of L Terentius Maximus from Italy (1st century CE).

There is another. A bird holding a string of pearls is a recurrent symbol on bowls from Nishapur, Iran (9th-10th century) to huqqa bases from northwestern India (19th century).

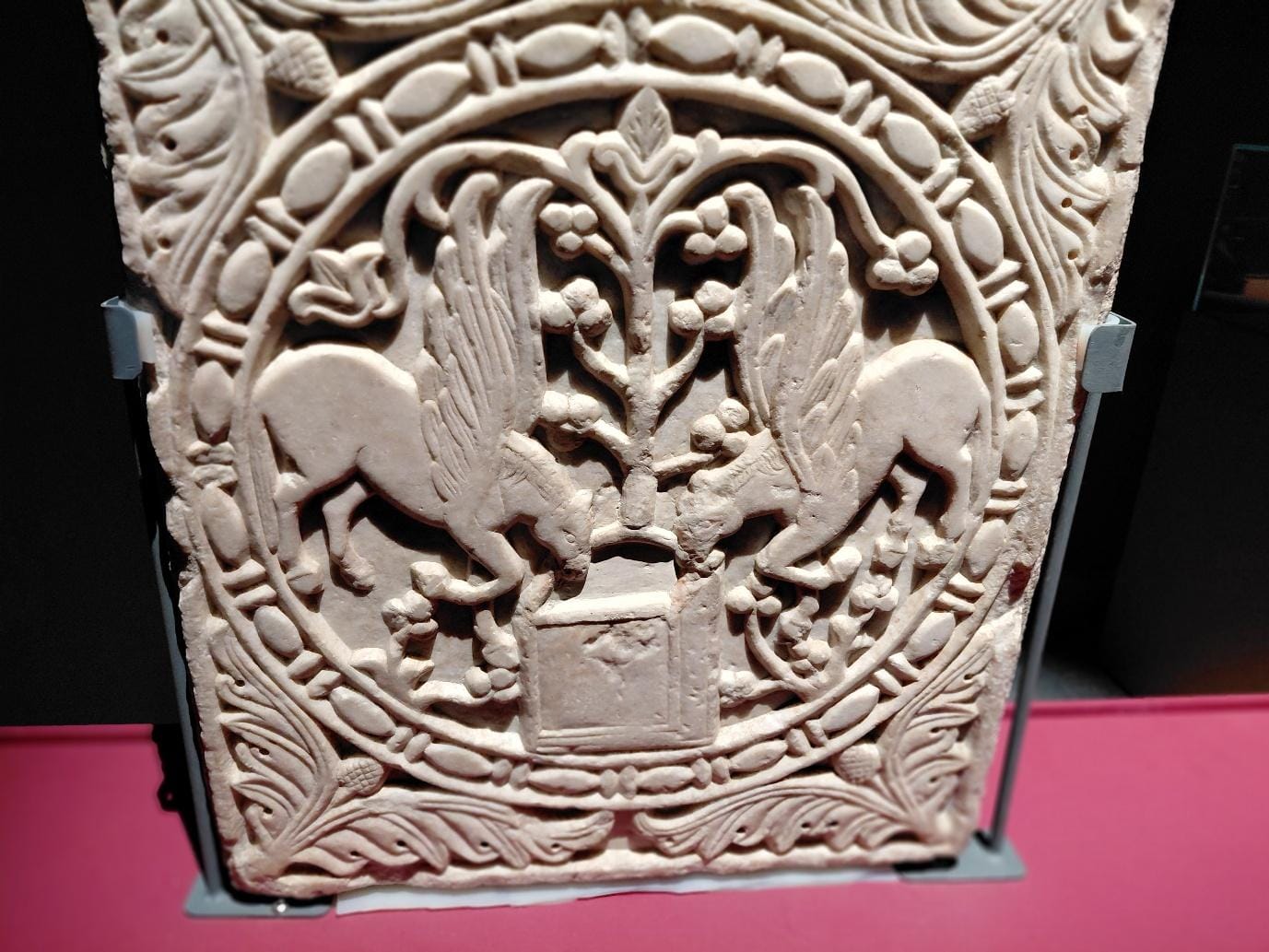

Winged animals were found on brackets in Butkara, in present-day Pakistan (1st-2nd century CE), on a marble panel of winged horses from a cathedral in southern Italy (10th-11th century), and in figures of hares on bowls and tiles from 14th century Iran, as well as on a copper handle from 12th century Khorasan.

The spread of winged horses from the Mediterranean to the Far East is evidence of ‘iconographic continuity’, says a text panel at the exhibition.

An ode to a past being forgotten

The exhibition isn’t self-explanatory; it requires a curatorial walk-through for visitors to decipher its larger message. The long text panels are pasted like ponderous books on the wall. Written in a rigid scholarly tone, they are not designed with the visitor in mind.

Many visitors breezed past the artefacts without reading much of the text, or lingering and examining. That is not a good sign. For an exhibition this political — let’s face it, telling the truth can itself seem like a radical, political act today — visitors need hand-holding. Meaning-making and pattern-finding are important visitor activities that every curator aspires to encourage in the gallery.

I was lucky, because Andrea Anastasio, director of the Italian Cultural Centre, gave me a nuanced, storytelling tour of the exhibits. He now plans to train other docents to give similar talking tours for visitors.

Even as this storytelling bit is being stitched together, the exhibition already stands as an important curatorial intervention in Delhi. The idea that there was a shared visual language of figures, motifs, and patterns — embedded with metaphorical value — may sound unremarkable to an art historian. But it is precisely this knowledge that is being deliberately forgotten in this century.

In a world where we have come to focus unhealthily on the unshared parts of history, the exhibition is an ode to viewing the past as a shared, flat timeline.

Rama Lakshmi, a museologist and oral historian, is ThePrint’s Opinion and Ground Reports Editor. After working with the Smithsonian Institution and the Missouri History Museum, she set up the ‘Remember Bhopal Museum’ commemorating the Bhopal gas tragedy. She did her graduate program in museum studies and African American civil rights movement at University of Missouri, St Louis. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)

This write up is another pseudo-Intellectual attempt to Dilute Cultural Sovereignty

This blog is a textbook example of academic sophistry – masquerading speculation as scholarship and attempting to forcefully weave a narrative of cultural homogeneity where none authentically exists.

The author’s premise is fundamentally flawed: Not every culture is a mere derivative or intersection of external influences. Civilizations are not weak, porous entities waiting to be permeated, but robust, self-generating ecosystems with intrinsic philosophical, artistic, and intellectual DNA.

Each culture has its unique evolutionary trajectory. The Indic civilization, for instance, didn’t require external validation or cross-pollination to achieve its profound depths of philosophical, mathematical, and artistic excellence. The suggestion that cultural achievements are primarily products of “interactions” is not just intellectually bankrupt – it’s a deliberate historical diminishment.

The so-called “museum as public intellectual” rhetoric is nothing more than a thinly veiled attempt to peddle a globalist fantasy. Museums should be repositories of verified historical evidence, not platforms for ideological engineering.

What the author calls “revisionism” is often a legitimate scholarly correction of colonial and invasive narratives that systematically distorted indigenous historical understanding. Restoring historical accuracy is not a crime – it’s an intellectual necessity.

This exhibition is not about shared stories. It’s about manufactured narratives, designed to erase the distinctive contours of civilizational uniqueness.

Scholarship demands rigor. This piece delivers only rhetoric.