Some people feel the rain, others just get wet. This Bob Marley quote stands true for Indian cities today and its inhabitants. What started as a welcome break from the scorching heat, calling for mandatory pakoras and chai, soon became a soggy ordeal for city-dwellers as the skies wept more and more. It’s not just the southwestern monsoon, which has historically shaped cultures and civilisations, but because people building roads and dams, and those responsible for development have not taken lessons in history. Nature doesn’t care for dams and roads, sky scrapers or human plans. Nature is untamed, unrestricted force that has given us life – something our ancestors understood and respected.

By mid-July, as India welcomes the much-awaited summer monsoon showers— relief from scorching heat—the urban dwellers brace themselves for the mayhem caused by clogged drains, damaged roads and flash floods. Major cities are flooded, low-lying settlements are submerged, and landslides result in casualties. Expanding city limits by occupying natural habitats and river floodplains exacerbates the situation. Dams have created a void in rivers, exposing and occupying previously undisturbed terraces and floodplains. The build-up areas in the cities are rising, the natural area is decreasing, putting added pressure on the drainage systems.

Although we spend crores in pre-monsoon preparations, urbanites always get caught between the actions of authorities and municipal cooperations and the force of nature. This love-hate relationship with the monsoons has become a defining feature of modern India. However, there are lessons from history that can help us recover and fall in love with monsoons once again.

Also read: More UNESCO tags for Indian sites is a good thing. Next big focus is to protect and conserve

Knowledge from ancient India

The advent of agriculture during the eighth millennium BCE facilitated the transition from a nomadic life based on hunting and foraging to a sedentary one, with tiny settlements forming along rivers or lakes. Water became a key enabler for this new way of life. With agriculture becoming early human’s newest hobby, settlements sprouted near the closest source of water such as Mehrgarh in Baluchistan, linked with Indus River system; Lahuradewa an early farming site adjacent to a lake in Upper Gangetic Plain, bounded by Sarayu River; and Bhirrana located on the banks of dried rived Ghaggar River in Fatehabad district, Haryana. Thousands of similar settlements covered many river basins or lakes in various parts of the subcontinent. Among these early farming settlements along the Indus and Saraswati River systems, culturally and social evolution paved the way for the emergence of India’s first urban cities.

The urban centres of the Harappan Civilization, such as Rakhigarhi, Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Dholavira, Lothal, are famously known for their advanced town planning, which includes impeccable and sophisticated drainage system, wastewater management and rainwater harvesting. Moreover, along with being traders, they were largely agrarian, requiring water for irrigation. To meet this need, they devised an extensive network of reservoirs, wells, canals. As a ‘riverine culture’, there must have always been a danger of seasonal floods, and to tackle this, Harappan Cities were enclosed and fortified.

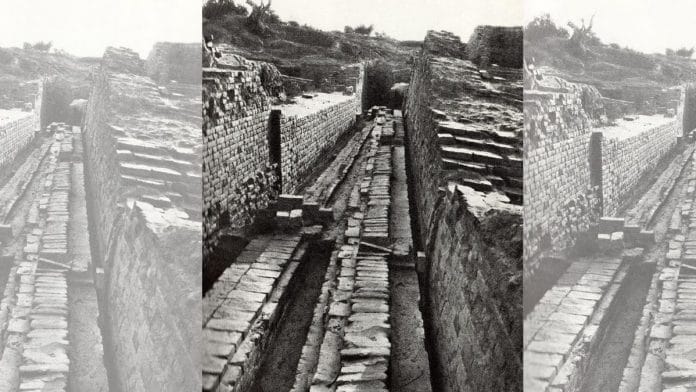

The drainage system was one of the most remarkable features of the Harappan cities. All the streets and lanes across neighbourhoods in Mohejodaro, Dholavira, Harappa, etc had drains. Additionally, houses had provision for managing waste-water with vertical pipes in the walls leading to chutes that opened onto the streets.

Recent excavations at Rakhigarhi revealed a series of covered and open drains with soakage pits at every street corner, where the drains turned at right angles. At Banawali, a small town in Haryana (closer to Rakhigarhi), similar soakage jars were found at every fixed point along the street. Mohenjodaro, one of the earliest excavated sites, provided remarkable evidence of water-management, sanitation and drainage system. Over 400 wells made of ‘wedged-shaped’ bricks were excavated, along with an extensive network of drains made of baked-bricks, closely fitted and sealed with mud-mortar. Wider drains were covered with limestone blocks.

According to Gregory Possehl (2002), small setting pools and traps were built into the system of drainage to allow sediment and other material to collect water. These, according to him, would be cleaned out periodically and attested to by ‘little heaps of greenish-grey sand that we frequently find alongside them’.

Meanwhile, Dholavira is the best suited example for present day municipal cooperation representatives when it comes to tackling rainwater. Located in Kachchh, Gujarat, people of Dholavira were well aware of their environment and understood the need for water-management in an arid area where water is scare.

This Harappan city, which evolved as a port, was densely populated (as suggested by the nature of structures excavated) and must have attracted traders and sailors on a regular basis. This meant that the city had to meet the basic water requirement. Large reservoirs were excavated around the city on two sides, which connected the two season streams – Mansar in north and Manhar in south. These were connected with a network of large-drains, which in-turn were connected with tanks located along the city walls. Series of wells were also well-connected with tank, which managed and stored rainwater, as indicated by a storm water drain leading to the reservoir near north wall. This water harvesting system would refill the reservoirs, helping the people of the city during dry period.

The people of Dholavira were aware of hydrology of the area and monsoon pattern, and used these things to help a city thrive during rainfall, which otherwise would have been inhabitable. It was these strategic tactics implemented by the city dwellers that made Dholavira one of the five largest Harappan metropolises.

Imagine if they had no idea about the elevation and inclination and understanding of hydraulic science, we wouldn’t have had this treasure to cherish.

The Harappans were a ‘riverine civilisation,’ with their settlements strategically located to protect the river terraces and, most importantly, the floodplains. They were aware of the scale of flooding, especially in the Indus basin, and were prepared for the inevitable. This practice continued with later cultures. For example, the Painted Grey Ware users on the banks of Ghaggar chose new locations for their settlements as the river dried up, moving to sites closer to the banks compared to their predecessors.

During the early historic period, such as under the Mauryan Empire, a lot of emphasis was placed on maintaining reservoirs and building dams. Large fortification walls were also built to help protect against the seasonal floods as seen in Kaushambi. In fact, ancient literature, including the Rig Veda, Yajurveda and Atharaveda have many references to the water cycle and management. Sadly, we’ve forgotten everything.

Also read: Collapse of Harappan Civilisation? Art of making shell bangles transcends time and boundaries

Chaotic cities of today

In the present context, riverbeds are captured, floodplains are used for constructing new buildings, and ecosystems are rapidly destroyed. The ancient knowledge of city construction has been forgotten and relegated to history books. Insights on rainwater harvesting, drainage, and sanitation from archaeological findings are rarely acknowledged. It’s no wonder our cities are drowning.

New Delhi, as nation’s capital, is a classic example of disastrous management by authorities. The area behind Red Fort, once the bed of Yamuna River, has now been converted into a road connecting much of the city to ISBT, the inter-state bus terminal. The floodplain in this area has been captured, turning the river into little more than a glorified drain. Since it is naturally a low-lying area, being the old riverbed, it floods every year during heavy monsoon season. The settlements around it are flooded, forcing residents to relocate.

The area adjacent to the Red Fort, known as Darya Ganj, is elevated. The old city of Shahjahanabad was built on a higher ground, keeping in mind the nature of Yamuna River. The road that periodically becomes submerged should never have been built there; it was constructed for our convenience, and now we have no right to complain. The tragic incident at Old Rajinder Nagar—where three UPSC aspirants died after the basement of a coaching centre flooded—was caused by drain clogging and the area’s a low-lying nature, which led to water stagnation.

Unfortunately, almost every other city is in this pathetic state. Perhaps it is time to go back in time and learn a thing or two.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. Views are personal. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Also, India failed to learn about the drainage system from Britain during the colonial rule.