I shall begin by saying that it is not often that we find ourselves happy when the legislative process in this House is concluded. But this time we feel that there has been some real good work done. In some respects, we would have wanted to go even further than the Bill has gone, but we know that in the present set-up, where economic inequality and the spiritual deprivation which it inevitably entails is tragically widespread and impinges particularly on the women of our country, we cannot have that kind of really simple, effective, and humane legislation that we want. Even so, Sir, the Special Marriage Bill registers a considerable advance in our present context, and for that, certainly, the House can congratulate itself.

Sir, we have seen during this debate not only what everybody expected, namely strenuous arguments to the brief of obscurantism put forward by my friends like Mr. Chatterjee, but also a very much more perilous symptom, namely, the reactionary revivalism which is still rampant in the ranks of the Congress Party—a revivalism to which almost unbridled expression was given by yourself when you were speaking from the floor of the House, a revivalism which had to be kept in check during the proceedings of this House by repeated interventions in the debate by the Prime Minister.

Now, these interventions of the Prime Minister were highly welcome, but they showed very clearly that the Congress Party, as a whole, far from being a party of progress, is very different, and all the force of its leader’s personality and prestige had to be brought to bear repeatedly throughout the proceedings to ensure the Bill’s passage without serious reactionary amendments. The speech we have just heard underlines the fear that I am expressing, and I think it bodes very ill for the party because it harbours within its ranks people who are so socially reactionary that they cannot possibly take a humane view of matters; they cannot possibly be parties to that kind of reconstruction which we want in the life and economy of our country.

I do not wish to speak entirely in a vein of seriousness because we have been discussing an institution that is so solid, which is so strong that we can afford to laugh at it. Just as a person can laugh at himself if he is self-confident about himself, so our society has laughed at the institution of marriage from time to time. I have heard somebody say that the married estate is like a beleaguered fortress; those who are outside want badly to get in, and those who are inside want equally badly to get out. Then, Sir, there was a wise Frenchman, Montaigne, who wrote in his Essays: “A good marriage would be between a blind wife and a deaf husband.”

We have been able to laugh at marriage in this way. Society has formulated these proverbs and things of that sort because, after all, it is an institution which has evolved spontaneously, naturally, and inevitably out of life. It is really a symptom of the solidity of the institution of marriage. In actual fact, marriage is a process of settling down, an assumption of generally humdrum responsibilities. Actually, the frenzies and the felicities of love, to which the world’s great literature remains incontrovertible witness, belong to an ambit of experience which, generally speaking, knows neither cause nor cure. Law is meant for the generality of marriages which, whatever the facilities for divorce or the lack of it, are more than likely to endure as lifelong associations. It is, therefore, in this context that we have to look at the problem.

Why is it that we have to provide for certain changes in our marriage law? It is because it is absolutely cruel, it is inhuman, it is derogatory to human dignity if we refuse reasonable facilities for divorce when marriage can no longer be continued on those terms which are self-respecting for human beings. We have heard arguments refusing reasonable facilities for divorce. Some members have tried to invoke transcendental and sacramental reasons, and some members have mentioned other kinds of reasons—technical and legal reasons. But we have to remember that if we refuse reasonable facilities for divorce, if this House—as the Prime Minister pointed out yesterday—compels two people to live together against their will; if we compel them to live together and to have physical association when the spiritual tie between them no longer exists, it will lead to unhappiness and serious consequences. It happens in life—there is no getting away from it—that sometimes two people cannot continue to live together without very serious damage to themselves.

Now, you make them live together, and I say that is vulgarity of the lowest order. If we are going to justify such indecency and vulgarity on the strength of something alleged to have been sanctified by scriptural or juristic ideas of some time or other, that is something which this Parliament would not accept. It is necessary for us to remember that we must not do anything which callously increases the unhappiness and frustration which is present in society. I know that happiness is not a commodity which the law can dole out, but the object of this law is—as has been repeatedly pointed out—the minimisation of misery. It may not perhaps secure the maximisation of happiness without concomitant legislation in the social and economic sphere on a very large scale, which the Government of today is not even prepared to contemplate. But at least let us try to minimize the misery. That is why we are going to pass this legislation, and that is why I say this House will wish it godspeed.

Then, Sir, the clause regarding “divorce by mutual consent” has come under fire during this debate, but that is in truth the very best part of the Bill. I have heard it said repeatedly that it is unknown to what some people have chosen to call “civilised jurisprudence.” Sir, a friend of mine with a flair for research tells me, quoting from Jackson’s Formation and Annulment of Marriage, 1951 edition, pages 20 and 21, that divorce by consent was allowed in Roman law and in the 18th Century Prussian Code. There is provision for it in Muslim law, and apart from the Soviet Union and China—countries for which Mr. Chatterjee and his friends have repeatedly expressed their distaste—Burma and perhaps Indonesia also today have provided for it. Besides, even if divorce by mutual consent had been frowned upon by every system of what we might choose to call “civilised jurisprudence,” even if divorce by consent was frowned upon by hidebound lawyers and obscurantist reactionaries, we should incorporate it into our society if that is how we feel our mutual relationship requires to be regulated. That is the conclusion which society has reached. There is no getting away from it. Divorce by consent is a matter which surely has been accepted rightfully by the House and will certainly be passed in a few moments’ time.

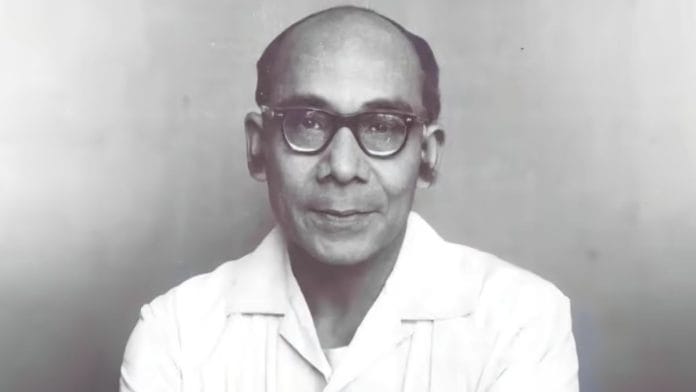

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.