The Economic Survey of India claims that the National Company Law Tribunal has 30,600 pending cases as of March 2025. It estimates that at the current disposal rate, clearing the NCLT backlog will take nearly 10 years. Even so, the 2026-27 budget allocation for the NCLT and related bodies under the Companies Act is lesser than the previous year, and capital allocation is not even half of the 2024-25 actuals under this head. In sum, NCLT capacity expansion is unlikely any time soon.

Can anything be done to unclog case pipelines at the NCLT? There are ways, we argue.

A significant portion of the NCLT’s workload, in the range of about 40 per cent, emanates from the Companies Act, India’s primary law governing companies. The Companies Act mandates companies to seek the NCLT’s confirmation or approval for several matters—ranging from an inter-state relocation of a company’s registered office to mergers—that warrant little to no application of the judicial mind. Removing these requirements—or replacing them with automated compliance checks—will free up the NCLT’s capacity. The idea is not blind deregulation, but to escalate cases to the NCLT only when shareholders or creditors are harmed by the actions of a company, its management or its dominant shareholders. Such low hanging rationalisation of the Companies Act will enable the NCLT to focus on cases that warrant deeper scrutiny or an application of the judicial mind.

In an earlier article, we demonstrated this proposition in the context of the Companies Act-requirement to obtain the NCLT’s approval for merger cases. An analysis of more than 3,000 merger cases showed that nearly 90 per cent of these cases are approved—after spending slightly more than a year at the NCLT. Additionally, in nearly 66 per cent of the merger cases that were disposed of, the NCLT had dispensed with the requirement to conduct shareholders’ or creditors’ meetings, suggesting that many of these cases need not have reached the NCLT in the first place.

In this article, we show yet another redundancy in the NCLT caseload under the Companies Act. This redundancy emerges from the power of the Registrar of Companies (ROC) to strike off inactive or dormant companies from the Register of Companies. Persons aggrieved by such orders are allowed to appeal to the NCLT. Strike-off related appeals generate about 35 per cent of the Companies Act-caseload of the NCLT, or 12 per cent of its overall workload. Our analysis of 3,419 such appeals in TheProfesseer’s database shows that nine out of 10 times, the NCLT reverses the ROC’s strike-off orders. This high reversal rate suggests many of these appeals are avoidable and that process improvements at the ROC could resolve most of them.

Also read: 10 years of the Commercial Courts Act—has the law delivered on its promise?

Striking off zombie companies

Contrary to popular belief, a company’s voluntary closure can be healthy. It frees up resources locked in the company, sending them back to the market for more efficient reallocation. This cycle falters when companies remain inactive for prolonged periods. Promoters lose interest in the formal closure. For all legal purposes, the company appears to be alive. Besides sub-optimal resource allocation, this creates risks of fraudulent transactions, money laundering and tax evasion.

Section 248 of the Companies Act seeks to mitigate these risks by empowering the ROC to “strike-off” such companies. The RoC only needs a “reasonable cause to believe” that a company has failed to commence business within one year of incorporation, or that it has not been carrying on business for the preceding two years, to initiate this action. Shareholders may also—subject to voting requirements—apply to the RoC for a voluntary strike-off.

While the bar is low for the State to wield this power and erase a company from existence, safeguards exist. The ROC is required to issue a series of public notices and forms in the Official Gazette before exercising this power. These notices are meant to inform stakeholders in the Company—both private actors and public—that the company has been listed for being struck off from the register. In essence, a strike-off is a largely procedural government action.

If the ROC wields this power improperly, the stakeholders affected by such a strike-off—the company’s shareholders, employees, creditors and even the tax department—may appeal to the NCLT.

Also read: NCLT bottleneck hinders India’s M&A boom. Govt’s fast-track framework ignores the real problem

High reversal rate of strike-off orders

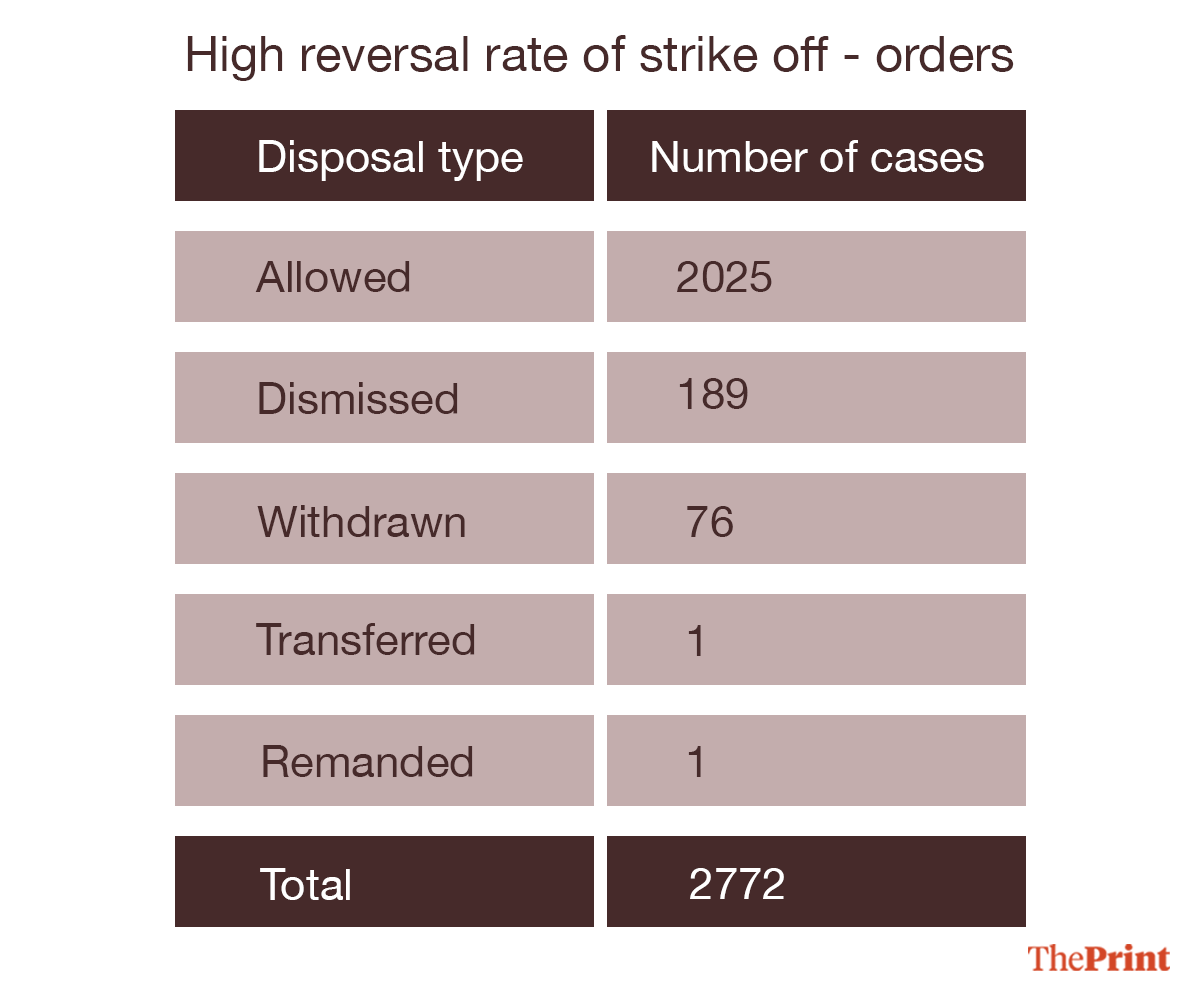

We analysed 3,419 such appeals filed between 2021 and 2025 across 11 benches of the NCLT. Of these cases, 2,772 have been disposed of. Graphic 1, which breaks down how these appeals were disposed of, shows that the NCLT allowed 90 per cent of the appeals.

What explains this high reversal rate of an ostensibly simple strike-off order? Our analysis of the text of the NCLT orders in these cases reveals three insights.

First, we find that in merely 12 per cent of the cases, the ROC’s strike-off order was reversed because it was “just and equitable” to do so. Presumably, this set of cases required the application of a judicial mind, warranting an escalation to the NCLT.

Second, in at least 40 per cent of the cases, the NCLT restored companies that were found to be active—a decision that the ROC itself could have reviewed with the proof of an ongoing business. In a few cases, we find that the company was inadvertently struck off due to a “mechanical process” and a “lack of manual verification and internal check”. Sometimes, the NCLT orders attribute it to a “mechanical generation of lists from the MCA-21 portal without sufficient internal checks”. These cases also could have been resolved at the level of the ROC, and did not warrant escalation to the NCLT.

Finally, at least 800 of the appeals allowed by the NCLT—amounting to a third of the total strike off orders reversed—were cases filed by governmental bodies/statutory authorities and regulators, with the Income Tax Department seeking a reversal in about 20 per cent of these. This is a classic example of wasteful government-to-government litigation.

In some of these cases, the ROC itself admitted to having defaulted on the statutory requirement of intimating the Income Tax Department before striking off the company. In some others, the RoC produced proof of having intimated the tax department, but the NCLT allowed restoration citing “public interests and interests of Government revenue”.

One of the cases in which the strike-off order was challenged by the Income Tax Department went on from April 2022 to May 2025, through 26 hearings, only to be dismissed due to non-prosecution from the office of the Principal Commissioner of Income Tax. An absolute drain on the State resources.

One arm of the government litigating against another—over its own procedural lapses—is both ironic and wasteful. Such cases not only undermine the sanctity of the ROC’s strike-off orders, but also relegate the NCLT to a fail-safe for procedural lapses of government departments.

Our analysis shows that about 12-15 per cent of the strike-off related appeals realistically warranted the application of a judicial mind. For the rest, the aggrieved company or the government department could have applied for a rectification order of sorts before the ROC itself.

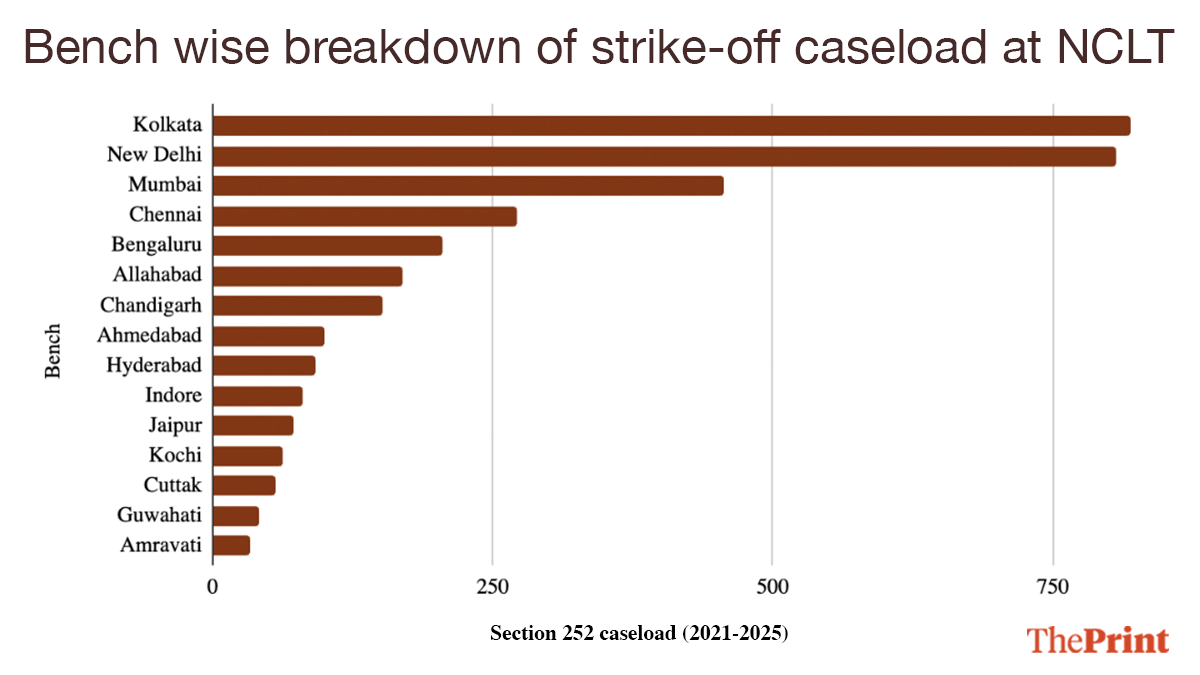

An approach that empowers the ROC to review its own strike-off orders, particularly where another government department seeks to reverse the strike-off decision, will relieve the NCLT of a non-trivial caseload burden. As Graphic 2 shows, such cases are disproportionately high in already burdened benches such as Kolkata, New Delhi and Mumbai. Allowing the ROC to hear a first review against its own orders will benefit these benches of the NCLT the most.

The system has stopped serving the litigant

A thorough rationalisation of such provisions of the Companies Act serves not only the NCLT, but also the company in question. An entrepreneur’s job is to focus on building a business that’s profitable for his shareholders and beneficial to his consumers. Making an entrepreneur run the rounds of the NCLT for procedural actions undermines the entrepreneur’s ability to build a viable business.

Our analysis finds that it takes about a year for a case of this kind to get resolved at the NCLT (316 days on average), with the median case taking six hearings. This is puzzling. The question before the NCLT in such an appeal should be a binary check of whether the ROC complied with the procedural steps before striking off a company. If yes—there is no reason for restoration, barring extreme exceptions. If not, restoration is the just outcome. If the ROC was vested with the power to make this binary decision while ending the corporate existence of the company, why escalate its review—especially given such high error rates—to an adjudicatory Tribunal?

Also read: Holding judges to account can’t be about collective conscience. It must fix a broken system

Finding the clog

Capacity and budget constraints are a common refrain for most developmental challenges in India. That, however, shouldn’t prevent us from maximising efficiency within our means and resources.

Our analyses of two casetypes that contribute to a significant proportion of the NCLT’s caseload under the Companies Act—merger cases and appeals against the ROC’s strike-off orders—suggests that the law can and must be rationalised to reduce its touchpoints with the NCLT.

The real solution lies in examining what is clogging the system—not mechanically repeating pendency numbers in government and other reports. An analysis of the fine print of case orders and litigation trajectories can offer solutions to allay the court’s workload problem in a more deft and economical manner while we await capital and resource augmentation of the NCLT in particular and the courts in general.

Gokul Sunoj is an associate at The Professeer. He tweets @GokulSunoj. Bhargavi Zaveri-Shah is the co-founder and CEO of The Professeer. She tweets @bhargavizaveri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)