The Securities Markets Code, tabled by Nirmala Sitharaman in Parliament, takes a decisive step in forcing regulatory convergence in India’s securities markets. It will govern not only the market for equities but also the market for derivatives of commodities ranging from wheat and soyabean to metals, oil, and electricity.

The upside is regulatory continuity. By empowering the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) to regulate equity and commodity derivatives, the SMC carries forward a policy, in place since 2015—consolidating all secondary market trading under one law. A single regulator and uniform rules across secondary markets lower the costs and frictions of trading across asset classes.

That said, the Bill’s “continuity” also entrenches New Delhi’s longstanding grip over commodity markets, perpetuating a regressive streak in an otherwise modernising financial landscape. The commodity derivatives market is vital for any economy as it allows buyers and suppliers to hedge their price risk. It also facilitates price discovery of the underlying commodity in the spot market.

A liquid derivatives market brings together diverse participants (producers, traders, speculators, investors) to trade future price expectations, creating transparent, forward-looking benchmarks. These benchmarks shape spot prices, guide production and consumption decisions, and reduce volatility for the underlying commodities.

In short, a liquid market in commodity derivatives is not merely desirable but imperative for disseminating price signals to the real economy. The Bill, by preserving the government’s discretionary powers to control commodities trading, impedes the creation of such a market.

State control over commodity markets

Government control over commodity trading has been a stubborn feature of market governance in India since World War II. It originated as part of wartime governance of British India, and was immortalised by the Indian government in the early years after Independence.

Historians such as Ritu Birla and Rohit De have noted that independent India often enforced these colonial controls more aggressively than the British themselves. The primary instrument of this dirigiste approach is the Essential Commodities Act, which allows both central and state authorities to control the production, storage, and circulation of goods deemed “essential.”

Under the aegis of this Act, the state deploys a suite of restrictive “control orders”—ranging from the imposition of stock limits and price ceilings to the mandating of specific cultivation areas and outright export bans. Crucially, violations of these control orders have been treated as criminal offenses.

Consistent with the inherently changing notions of public interest, the reasons for invoking such controls changed over time. While the original justification for these controls was the equitable distribution of essential commodities during scarcity in the 1950s, it morphed into earning foreign exchange in the 1970s, and preventing people from profiteering in the late 1980s. In the last two decades, controls under the law have been imposed on commodities ranging from onions to jute and petroleum.

SMC Bill perpetuates commodity controls

The proposed SMC Code Bill entrenches similar state interventionism within India’s commodity derivatives complex. By empowering the government to determine which commodities are eligible for derivative trading, the Bill risks reviving the old Controller of Capital Issues mindset. The parallels are stark: it is equivalent to the state hand-picking which private enterprises may list on public exchanges, or deciding—by fiat rather than formula—which equities qualify for the futures and options (F&O) segment.

In the equity markets, SEBI maintains a transparent, rule-based framework to determine which shares are eligible for trading in the F&O market. Stock exchanges operate within these predefined parameters to admit or remove securities. While this rules-based framework is grounded in market capitalisation, turnover, and liquidity, the commodity sector remains untethered from such objective metrics. The SMC Bill’s mechanism for declaring “eligible” commodities mirrors the opaque discretion of the Essential Commodities Act, favouring administrative whim over the predictable, data-driven governance essential to a modern financial centre.

The SMC falls desperately short in this regard. It empowers the government to notify the “commodities in respect of which a derivative may be entered into or made by any person”, in consultation with SEBI. This effectively splits the regulatory jurisdiction over commodity derivatives between the government and SEBI, a feature that we have seen in Indian banking with sub-optimal results. The Bill does not mandate either the government or SEBI to put in place a rules-based framework for such notifications.

This means that a commodity, say oil, may be eligible for trading in the futures and options segments today, but may be abruptly withdrawn in the future. Additionally, as discussed in the previous article on the Securities Markets Code, these problems of opaqueness and unpredictability are exacerbated by the wide powers conferred on SEBI to issue directions in the interest of development of the securities markets, and wider powers conferred on the government to issue directions to SEBI in the public interest.

Also read: SEBI does not need unlimited powers – here’s what’s wrong with the Securities Markets Code

A demonstration of (yet another) ban gone awry

Our apprehensions with government control over commodity derivatives are not merely theoretical. In December 2021, SEBI shuttered futures trading for seven key agricultural commodities. Covering over 70 per cent of traded volumes, the ban was justified as ‘essential’ to control food inflation. In fact, it followed a narrower suspension earlier that year, reflecting a long-standing suspicion in New Delhi that speculative activity in derivative markets bleeds into the prices paid by consumers at the local mandi. How it is SEBI’s job to control food inflation remains unclear. Even so, the ban was imposed and continues to date.

The ban has proved to be a masterclass in unintended consequences. The empirical data suggest that the intervention has failed its primary objective while eroding the structural integrity of the agricultural economy.

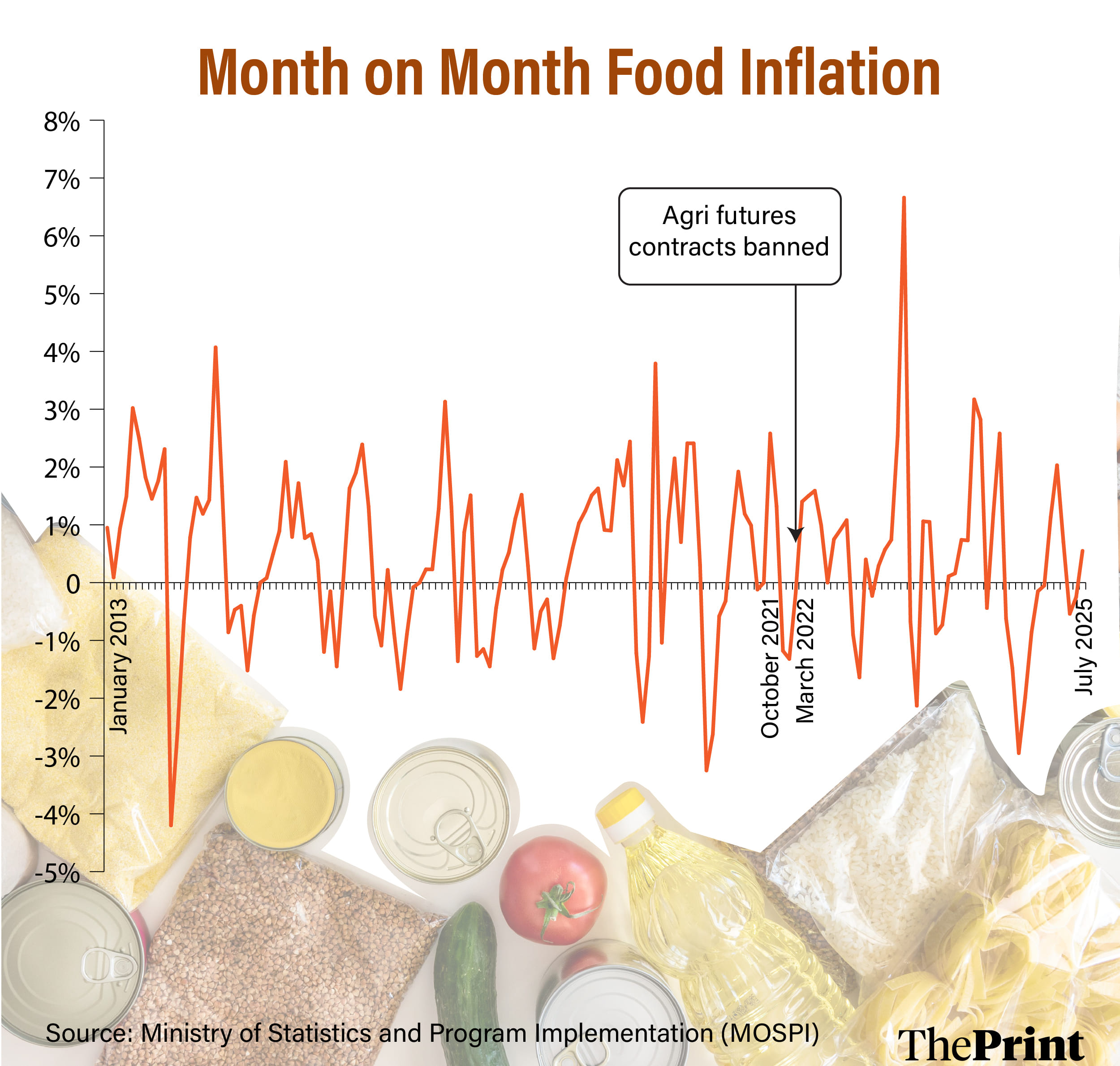

Analysis of month-on-month food inflation over the past 12 years reveals a striking continuity. The rhythmic pulses of price volatility observed before 2021 have largely remained unchanged. Indeed, the most significant spike in recent memory occurred in June 2023—well into the ban’s tenure. Detailed research on the spot prices of the commodities, whose derivatives were banned, is consistent with these findings.

Conversely, the deflationary turn in late 2025, which saw food inflation plummet and drag the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) to a mere 0.5 per cent, occurred without any assistance from a functioning futures market. The conclusion is hard to avoid: the ban has had no meaningful impact on food prices.

What it has done, however, is blindfold the producer. By stripping away the mechanism for price discovery, the state has deprived farmers of a vital forward-looking benchmark. In the absence of a hedging tool, producers were left defenceless against the recent collapse in spot prices—the very “protection” the state ostensibly sought to provide.

The failure of this ban is yet another demonstration that when the state attempts to suppress market signals, it does not solve the underlying problem; it merely destroys the information required to manage it. As SEBI prepares for its next review of this ban in March 2026, the case for rescinding it is not merely a matter of economic efficiency, but of regulatory credibility.

Conclusion

The Securities Markets Code cannot be confined to simply merging fragmented securities-related laws in India. Meaningful reform requires lawmakers to question the need for such 1970s-style controls over the Indian financial market. Decades of state control have damaged India’s commodity markets. Extending this control to derivatives makes even less sense.

Bhargavi Zaveri-Shah is the co-founder and CEO of The Professeer. She tweets @bhargavizaveri. Harsh Vardhan is a management consultant and researcher based in Mumbai. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)