Collectivisation was seen as the panacea for the problems of India’s agriculture in the 1950s. Chaudhary Charan Singh’s alternative to this was small-scale peasant farming: it offered higher productivity, better soil fertility, and greater employment opportunities. More importantly, it aligned with democratic values.

Charan Singh had been active in supporting the legislation for Zamindari abolition, debt redemption for farmers, and the Bhoodan movement of Vinobha Bhave. He argued that redistributing land to landless labourers and small farmers would not only reduce inequality but also improve agricultural productivity.

In his book, Joint Farming X-Rayed (1959), Charan Singh wrote that the West enjoyed surplus land but had limited labour. India was on the other end of the spectrum: it had an excess workforce, a short supply of land, and scarce capital resources. Thus, large–scale ‘tractorisation’ and capital–intensive farm mechanisation were not realistic options.

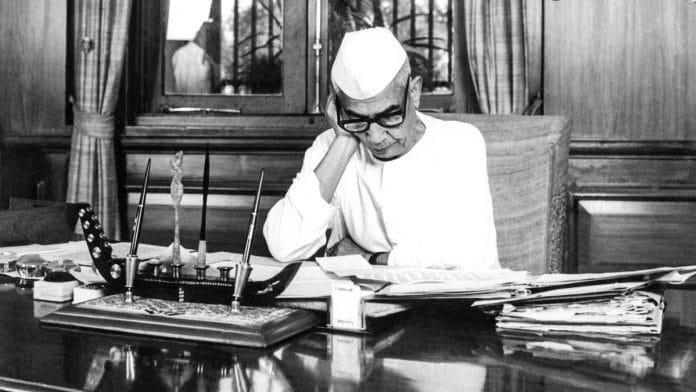

Unlike Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and the Planning Commission, Charan Singh was against the thrust toward industrialisation, convinced that the foundation for India’s economic development lay in smallholder agriculture.

In 1956, the government—with Soviet assistance—set up a Central State Farm on 12,000 hectares of land in Rajasthan’s Ganganagar district. The project was nowhere close to the success of the National Seeds Corporation of India, established in 1963, which worked on the hub and spoke model, with individual farmers growing seeds as per accepted production protocols. Finally, after mounting losses, the State Farms Corporation of India was merged with the National Seeds Corporation, which depended on the smallholder farmer. It offers retrospective endorsement to Charan Singh’s faith in smallholder agriculture.

Charan Singh’s electoral victories

Although Charan Singh had his differences with Nehru, the two held each other in high esteem. Charan Singh had also been colleagues with former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri as a Parliamentary secretary and later as a cabinet minister. Their views were in accord on matters relating to Zamindari abolition, debt relief, and land consolidation. After Shastri’s death and Indira Gandhi’s ascent to power in 1967, Charan Singh was no longer comfortable with the Congress and its style of functioning. He moved out and joined the Jan Congress. Later, he went on to lead the Bharatiya Lok Dal, and founded the Bharatiya Kranti Dal and the Lok Dal.

Charan Singh became the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh twice, albeit for short intervals of time. Arrested by Gandhi for his opposition to the Emergency, he merged the Lok Dal with the Janata Party, and held the home and finance portfolios in the Morarji Desai cabinet, as well as the status of Deputy Prime Minister. He was also the Prime Minister for six months, though he could not remain in office on account of the Congress withdrawing its support. He won all six Assembly and three parliamentary elections he contested—such was his connection with the grassroots and his voters.

This brings us to the larger question of ‘farmers’ movements’ in electoral polity. Charan Singh dropped the word ‘kisan’ (farmer) from his party and focused on ‘lok’ (people) to gain greater acceptance.

Also read: Charan Singh exposed failures of Soviet collective farming. And saved Indian agriculture

Elections and farmers’ movements

After Charan Singh’s death in 1984, the mantle of farm leadership fell on another leader from western Uttar Pradesh, Mahendra Singh Tikait. In 1988, Tikait mobilised 5 lakh farmers and occupied the Boat Club and the Raj Path in Lutyens’ Delhi, compelling the Rajiv Gandhi government to concede to all his demands. These included higher remunerative prices for sugarcane and the waiver of electricity and canal dues. In fact, Uttar Pradesh chief minister ND Tiwari was specially flown in to Delhi to sign the agreement. While Tikait took the precaution of not directly participating in electoral politics, his son Rakesh Tikait fought elections as a candidate of the Bahujan Kisan Party from the Khatauli seat and finished a distant sixth. He also reverted to the Lok Dal, but could not win the Parliamentary seat at Amroha. Devi Lal’s Indian National Lok Dal also lost steam after his death, winning only one seat in the Assembly elections in 2019 and two in 2024.

Former UN bureaucrat Sharad Joshi of the ‘Bharat versus Indian’ fame launched the Shetkari Sanghatana in Maharashtra in the late 1970s to demand remunerative prices of onions, sugar cane, tobacco, milk, paddy, and cotton. He also campaigned for the liquidation of rural debts and against a hike in electricity tariffs and State dumping in domestic markets.

Joshi’s movement soon spread to Karnataka, Gujarat, Punjab, and Haryana. As an economic liberal, he supported the WTO because he believed that Indian farming could be profitable if farmers had access to global markets. He launched the Swatantra Bharat Paksha (SBP), which won five seats in the 1990 Maharashtra Assembly elections. However, Joshi himself could not win any election as a candidate of the SBP. Later, he became a member of the Rajya Sabha with support from Shiv Sena. He is acknowledged for organising the Shetkari Mahila Aghadi (SMA), which ensured property rights for lakhs of rural women.

After the heady success of the farmers’ agitation in Punjab in 2020-21, leaders from 14 farm unions pooled their resources to contest the 2022 Punjab Assembly elections under the banner of the Samyukta Samaj Morcha (SSM). The SSM failed to win any seats, with many candidates losing their deposits. SSM chief Balbir Singh Rajewal himself lost the Samrala seat, managing merely 4,676 votes, while the Aam Aadmi Party’s winning candidate received 57,557.

The lesson is that agrarian concerns must be framed as part of a larger political discourse. Voters want their leaders to address the entire range of governance issues and not just a part of the spectrum.

This is the second article in a three-part series on smallholder agriculture.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Until recently, he was director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)