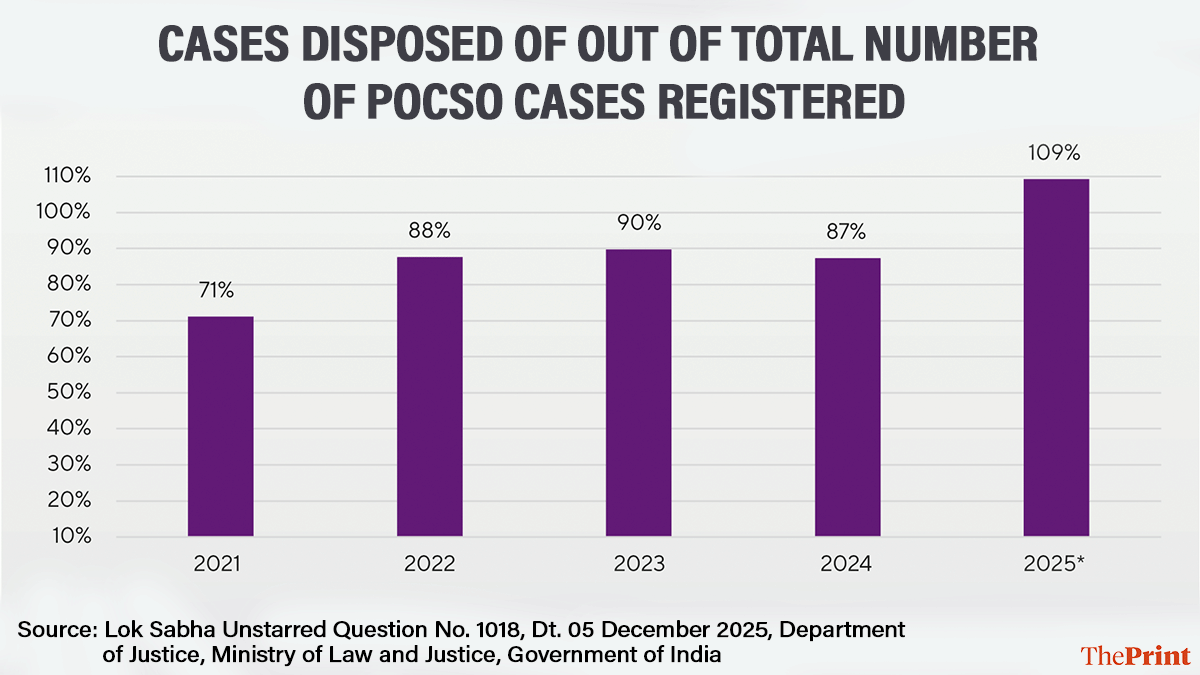

New Delhi: The year 2025 saw a significant uptick in the disposal rate of POCSO cases in the country, which went up to a 109 percent, compared to 71 percent in 2021, signalling an increase of 38 percentage points over the last five years.

Put simply, the number of POCSO cases decided exceeded the number of the POCSO cases registered all over the country for the first time.

“A notable shift is observed in 2025, when the disposal rate in POCSO alone reached 109 percent, marking the first year in which disposals surpassed registrations. Thus indicating that the courts not only addressed newly registered cases but also succeeded in clearing a portion of pending cases from previous years,” the report published by the Centre for Legal Action and Behaviour Change for Children (C-LAB) said.

It added that achieving this threshold represented a positive development and signalled improved responsiveness in the handling of POCSO cases. The report, titled ‘Pendency to Protection: Achieving Tipping Point to Justice for Child Victims of Sexual Abuse’, an initiative of India Child Protection (ICP), relied on data from the National Judicial Data Grid, National Crime Records Bureau, and Lok Sabha questions and answers.

Established in 2005, the ICP is a leading child rights protection organisation dedicated to combatting child sexual abuse and related crimes, including child trafficking, exploitation of children in the digital space, and child marriage.

Its research on the extent of Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) available in the digital space was instrumental in the formation of the Rajya Sabha Parliamentary Standing Committee (headed by M. Venkaiah Naidu) to prevent sexual abuse of children online and access to online child sexual abuse material, the ICP website says.

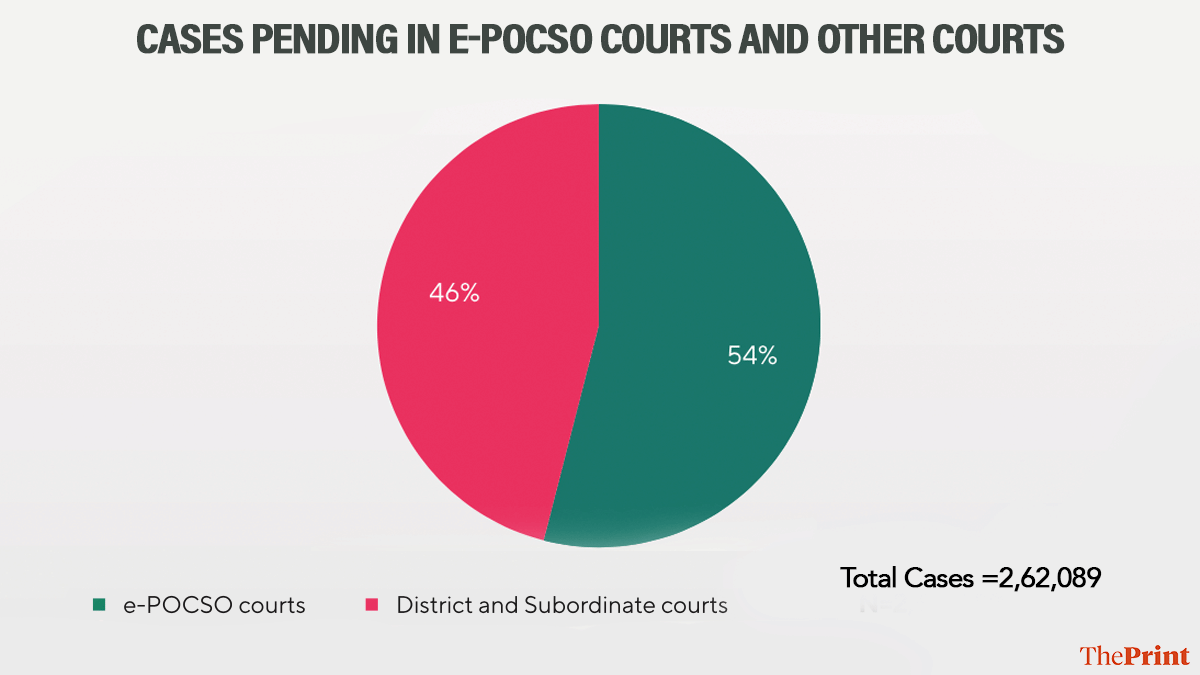

The break-up of POCSO cases shows that, as of 2025, 54 percent pending or undecided POCSO cases were pending before the e-POCSO courts, while the remaining 46 percent were pending in the district and subordinate courts.

According to PIB, there are 755 fast track special courts in the country, of which 410 are exclusively for POCSO cases, and are known as e-courts.

Also Read: Child protection to ‘moral policing’ tool: How POCSO Act is leaving courts conflicted

Conviction rate low

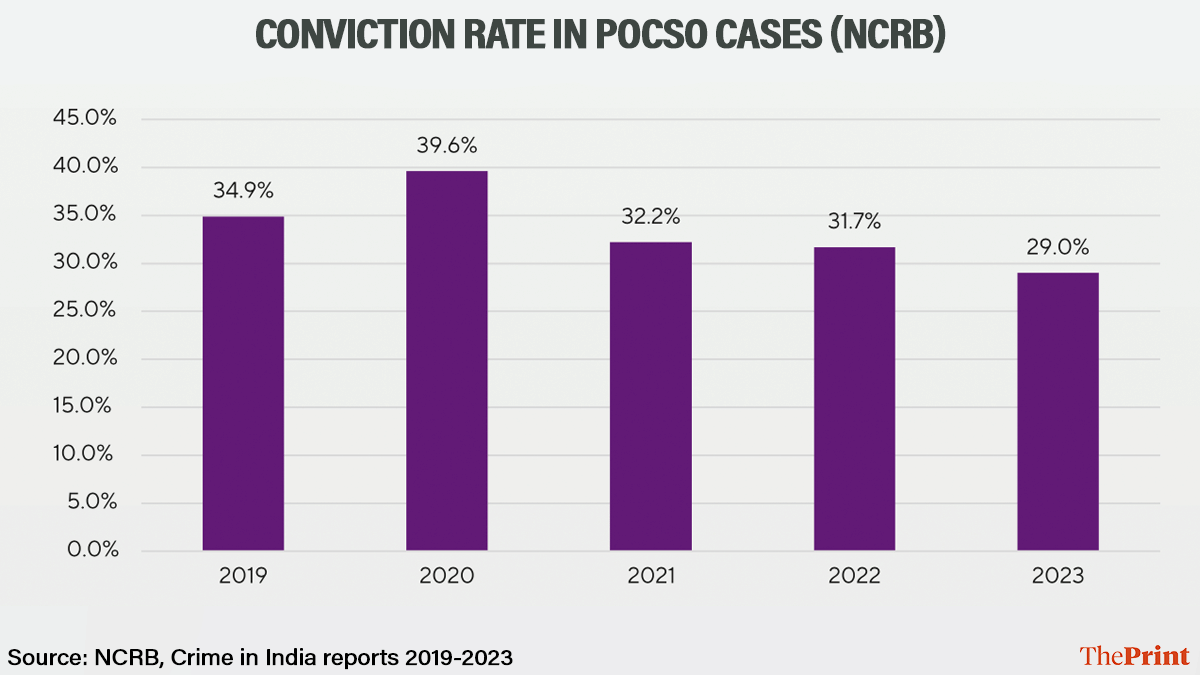

The conviction rate in POCSO cases, however, declined by 6 percentage points, from 35 percent in 2019 to 29 percent in 2023.

The conviction rate in cases disposed of by Fast Track Special Courts (FTSCs) was also substantially low. For instance, in 2024, the national conviction rate for POCSO cases disposed of by FTSCs stood at only 19 percent.

This was attributable to repeated adjournments, along with structural constraints like vacancies, limited infrastructure, and uneven state participation.

The conviction rate for 2025 has not yet been disclosed, the report’s authors told ThePrint.

An empirical study of POCSO enforcement across Indian states reports an average case duration of about 510 days, with convictions taking longer than acquittals and most states exceeding the one-year statutory timeline to complete the trial. The Act mandates that the investigation, along with the trial in POCSO cases must be completed within a year’s time.

“A decade-long judicial data study on POCSO highlights that more than half of all cases involve serious penetrative offences, yet the system struggles with delays, low completion rates, and wide inter-state variation in disposal patterns,” the report said while flagging the inordinate delay in the completion of POCSO trials.

Placing the findings within the broader justice framework, Purujit Praharaj, director (research), India Child Protection told ThePrint, “India is entering a decisive phase in its response to child sexual abuse. When disposal of cases outweighs registration, the system moves from intent to delivery.”

He also told ThePrint that, according to their research, it was clear that delays aggravate the harm experienced by child survivors. “Sustaining this pace is essential if child-sensitive, time-bound justice is to become a standard practice,” he said, while adding that strong legal deterrence is the most effective safeguard to protect children from such crimes.

In 2025, until 2 December, the number of POCSO cases instituted in all courts across the country stood at 80,320, while the number of cases disposed of by these courts was 87,754.

While the overall number of criminal cases disposed of by district courts increased by 9 percentage points between 2021 and 2025, the number of POCSO cases disposed of by these courts in the same period increased significantly by 38 percent.

This year’s report also said that a “tipping point” had been reached in India’s justice system, where it was moving from just managing the existing backlog to actively reducing it. Although this is not the first study of its kind, its results are unparalleled.

The major aim behind this was to see the status of POCSO cases in India, with special regard to the disposal, pendency and conviction rates.

Making further sense of these findings, Dr Swati Jindal Garg, Advocate-on-Record, told ThePrint that although the report seems to be “the golden lining to a dark cloud”, suggesting that disposals are taking place at a faster rate, it’s important to decode why the disposals are happening so soon.

“Certain questions need to be asked, like are the legal protections being bypassed, or are there more fictitious complaints being filed where complainants turn hostile and abandon the case midway? Was the complaint filed only to teach someone else a lesson? The possibility of collaboration taking place between the investigating authorities and the accused, leaving the latter scot-free cannot be ruled out either,” she said.

Garg also argued that the actual picture will only become clearer once it is known if the rising disposal rates are due to better management of POCSO cases or due to certain persons bypassing protections placed by the law.

What the data says

In the last decade or so, India saw a gradual increase in the reporting of child sexual abuse incidents under the POCSO Act, signalling greater awareness and access to justice.

At the same time, there is also considerable strain on the criminal justice system— attributable to factors like delay in investigation, prolonged trials, and high pendency—which in turn hamper timely delivery of justice to child victims, their families and society.

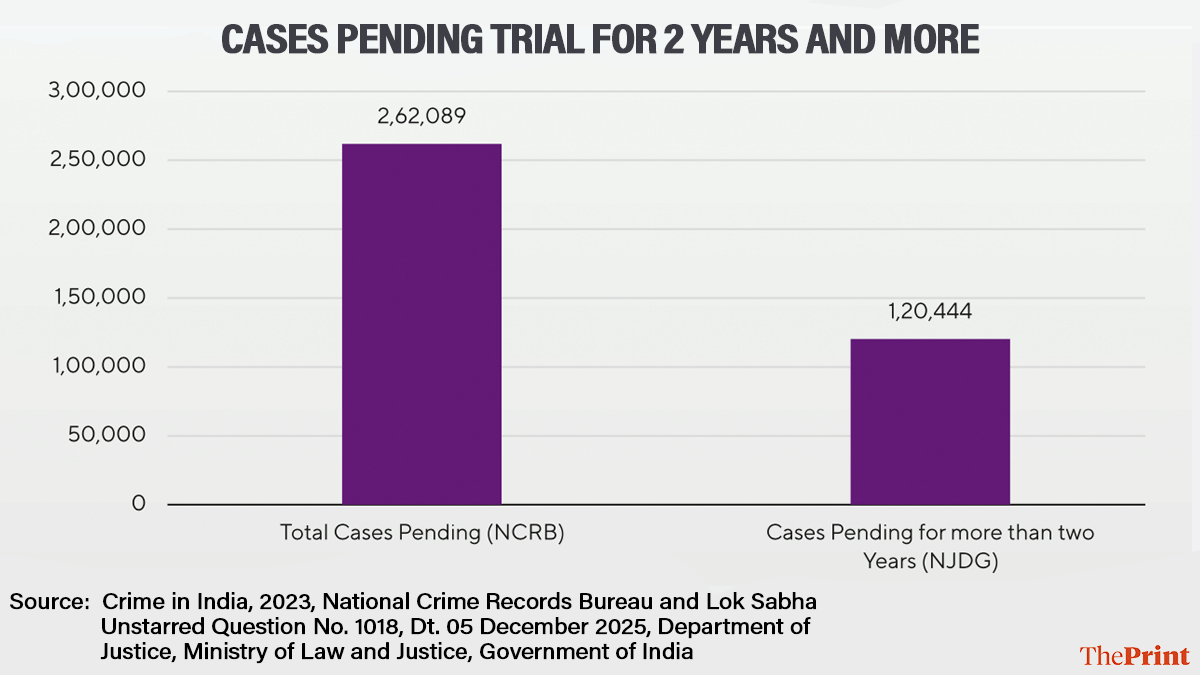

At the end of 2023, there were a total of 2,62,089 POCSO cases pending in courts.

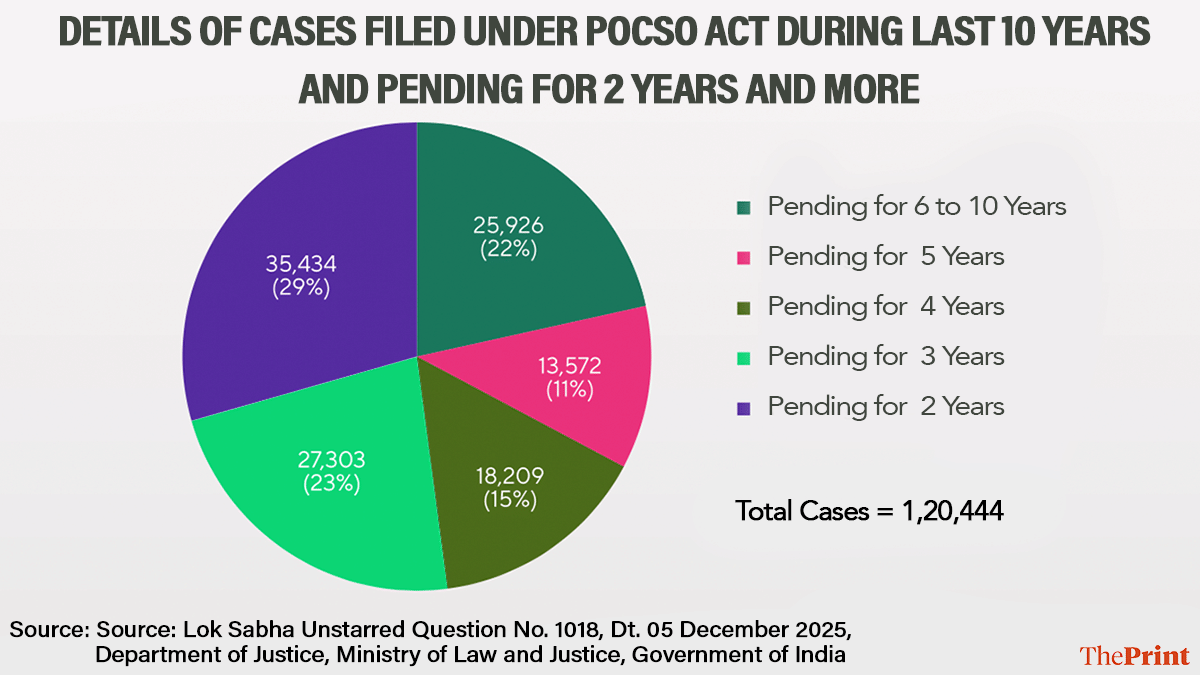

Of these, as many as 1,20,444 POCSO cases had remained undecided for over two years.

Simply put, this meant that 46 percent of all pending POCSO cases at the end of 2023 were older than two years, while 33 percent of these cases were pending for half a decade or more.

The report also highlighted a “clear mismatch” between the number of POCSO FIRs recorded by NCRB and the number of POCSO cases registered for trial in courts as reported by the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG). Over three years, that is, 2021 to 2023, the number of cases registered in courts was significantly higher than the number of FIRs filed.

“As per NCRB, in 2021, 53,874 cases were registered under POCSO. Of which, 51,129 were investigated and charge sheets were submitted in courts for trial. Contrastingly, NJDG records 95,238 POCSO cases were registered with courts for trial during the same year,” the report said, pointing to the discrepancy between NCRB and NJDG data.

Explaining this mismatch between NCRB and NJDG figures, ICP director Purujit Praharaj told ThePrint that NCRB comes under the home ministry, while parliamentary questions come under the ministry of law and justice. “This data gap shows that the two ministries are working in silos, and the number of FIRs filed under POCSO Act are less than the number of cases initiated for trial. Our guess is that since the NCRB simply collates data from other states and compiles it, there could be some discrepancy there.”

How different states fared

According to state-wise data given in the report, 24 of the 28 states in India had disposal rates of above 100 percent in 2025, meaning that these states were not only disposing the registered POCSO cases in that year, but also disposing cases from previous years.

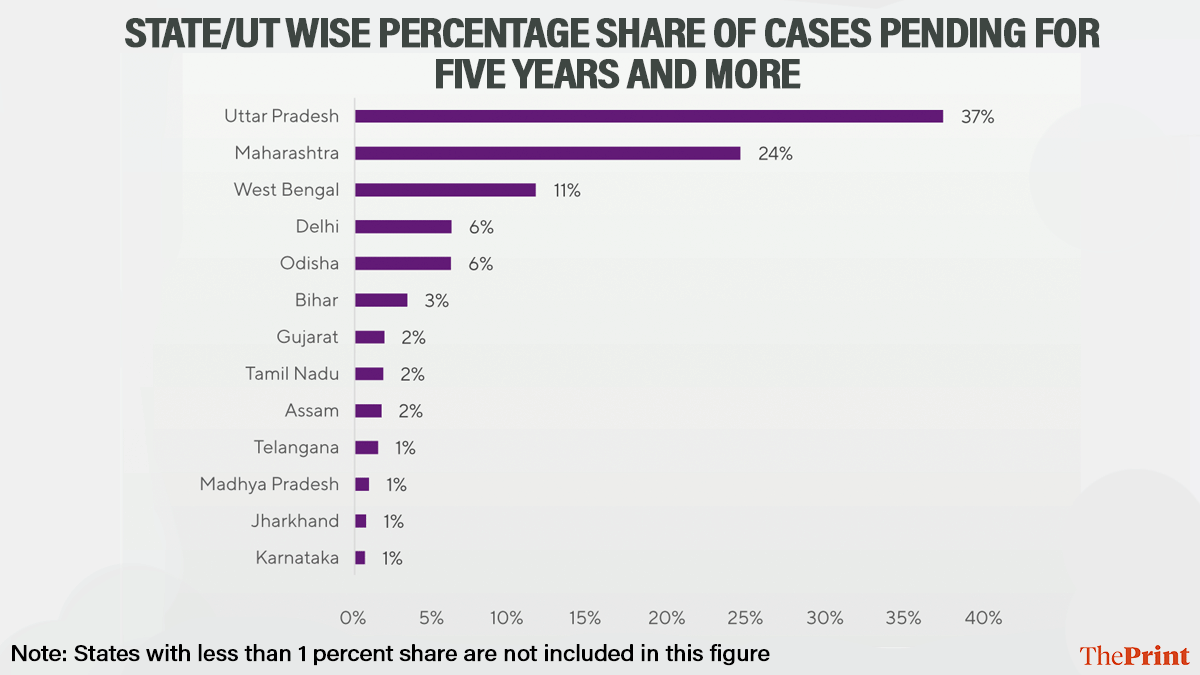

Among all states, Uttar Pradesh alone accounted for 33 percent of all POCSO cases which were pending more than two years, followed by Maharashtra and West Bengal, which stood at 23 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

Seven states and UT had disposal rates more than 150 percent. Anything above 100 percent indicates that the state has successfully disposed of cases from previous years as well, and not just the cases of 2025, leading to an overall decrease in the pendency figures.

States that fell below the 90-percent mark included Jammu and Kashmir, which had a 55 percent disposal rate, followed by Meghalaya at 43 percent, and Tripura at 79 percent.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Ladakh, and Mizoram reported no POCSO cases for 2025.

The 82-page report also suggested providing technical and administrative support to state judiciaries lagging behind in disposal rates of POCSO cases.

“States and Union Territories that are falling behind the national average in disposing of POCSO cases require all necessary technical and administrative assistance,” the report said, adding that this support could include targeted training programmes for judges, public prosecutors, and law enforcement agencies, along with measures to enhance forensic and investigation capabilities.

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also read: POCSO law must protect, not punish young people for consensual relationships