New Delhi: During the Covid pandemic, a large pile of uncollected garbage outside Aishwarya Sunaad’s house in Karnataka made her realise that she didn’t know who the local area representative was. The frustration gave her the idea of Civinc, an app that digitises civic data and connects citizens with their local representatives and municipal workers.

“In India, issues like outdated documents and uncleared garbage persist because the people responsible are hard to reach. This problem is across classes and regions. That motivated me to collect civic data because it is our right to know these contacts,” Sunaad, head of concept development and team lead of Civinc, told ThePrint.

Civinc consolidates the contact information of local elected representatives, municipal employees and department heads in a single interface, enabling residents to contact them directly, access civic services and report grievances. Users can also monitor works and track updates, all in real time. Problems can be reported via ward-specific QR codes and employee responsiveness can be tracked. The app also helps in public recognition of active officials and push for better service delivery. Users can further flag incorrect data, suggest updates, and view performance reviews.

Basically, the app helps ordinary citizens know exactly whom to call when their garbage goes uncollected, the road is broken, or a government form needs updating, and aims to make governance more transparent, responsive, and efficient.

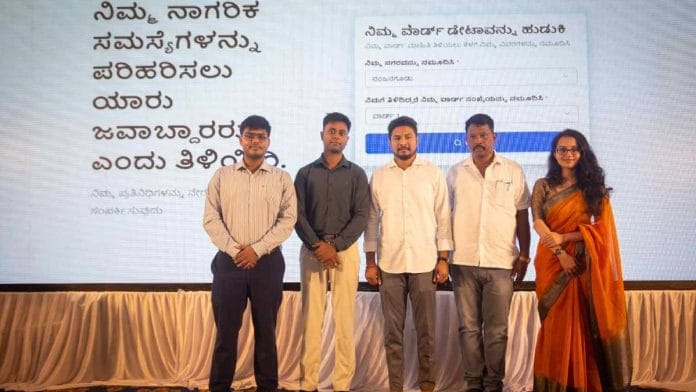

The student-built app was launched this month in Nanjangud, Karnataka, with the project conceptualised by Sunaad during her time at Ashoka University, under the mentorship of Debayan Gupta, Assistant Professor of Computer Science. It is supported by the university’s Isaac Centre for Public Policy (ICPP) and Mozilla Responsible Computing Challenge. The challenge supports the conceptualisation, development, and piloting of curricula that empowers students to think about the social and political context of computing.

Technology development was led by Harsh Raj and Aditya Sinha from National Institute of Technology, Jamshedpur. Further, Nitish Kumar and Kishan Kumar, political science scholars at Jawaharlal Nehru University, spent months conducting fieldwork in Delhi’s municipal offices to understand how civic data is stored and shared.

“We now have a system where complaints are raised directly with municipal employees. If an employee handles a certain number of complaints, their work is made visible to others on the app. This visibility becomes important to ensure accountability. Because of decentralisation, there is no other dashboard-like system in an understaffed government to track performance. So, we need to involve government employees and stakeholders, giving them the agency to address problems,” Sunaad said.

To make the app more accessible, all information is available first in the local language, with the option to switch to English or Hindi.

MLA Darshan Dhruvanarayana, speaking at the launch, said: “Nanjangud is proud to lead the way as the first non-metro city in the country to digitise its civic data.”

“Giving citizens direct access to officials who are responsible for essential services makes governance more transparent, responsive, and efficient. This is a youth-led project, and I believe we should work collaboratively with the country’s youth to conceptualise interventions to solve problems.”

Also Read: MCD is rounding up sterilised, friendly dogs just for optics—a moral and scientific failure

‘Visibility plays huge role in motivating officials’

Civinc is a result of interdisciplinary collaboration. Sunaad’s training in social anthropology made her understand how bureaucratic opacity and citizen apathy often reinforce each other.

“We have drawn from the research of Dr Abhijit Banerjee (Nobel Prize winner and Indian American economist) on administrative accountability in Delhi. He found that visibility plays a huge role in motivating local officials. Our app is an extension of his idea. By making visible the work of faceless municipal employees, we offer recognition as incentive for them to be more proactive in delivering essential services,” she said.

Sunaad added that the vision of Civinc is not to find a foolproof solution to administrative lapses but to set an example of projects that enable better governance and address the pessimism that stops citizens from civic participation.

“Out of 100 calls placed to municipal employees by citizens, even if 20 grievances are addressed on time, that’s a win in making our urban spaces better, compared to when people had no idea where to escalate a problem or who to speak to,” she said.

Nanjangud’s municipal employees were initially hesitant to the idea of their official numbers being made public, fearing they’d be flooded with calls. But the government pushed to make the data public, because previously most of the manpower was spent handling misdirected complaints, according to Sunaad.

Civinc works with the local government to maintain and update municipal data free of cost. Through an MoU, each participating city designates a government point of contact, usually a municipal employee, who shares weekly updates. This system removes the need for a separate tech department and officials can directly reach out to the Civinc team whenever there is a staff change or new contact information.

Data accuracy is also strengthened through citizen feedback, as anyone using the app can flag incorrect information. In case several people report the same issue, the app’s data team can review it and check with the government official for confirmation.

Civinc’s team is conducting workshops in colleges, schools, and residential communities to encourage them to take ownership, raise complaints and hold officials accountable rather than staying passive regarding civic issues.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Why Jaipur’s municipal mess is India’s problem too