Jaipur: It’s a quiet morning at Jaipur’s Pitambara Peeth, save for young voices synchronously chanting the Gayatri Mantra. A watchful guru corrects any deviation from the rhythm. Located on the outskirts of the city, this religious centre is home to one of Rajasthan’s 26 government-aided Ved Vidyalayas — free residential schools dedicated to producing the Hindu priests of tomorrow.

Here, boys between the ages of 10 and 17 study ancient texts and receive rigorous training over the course of five years to become the future “protectors” of Sanatana Dharma, say students and teachers.

In addition to their pursuit of Vedic knowledge, the boys must also attend a typical school. To fit it all in, every minute of their schedule is tightly mapped from 4.30 am until bedtime at 10 pm.

“We will get a lot of time to watch television and use our phones later in life. But this is the time to do hard work and to serve Veda maata properly,” says 17-year-old Pitambara student Govind Mishra, who comes from the state’s Sikar district.

“My father is a pandit. My grandfather is a pandit. I was inspired by them. I think people in our generation should be interested in Sanatana Dharma,” he adds.

It’s a cause for which the Ashok Gehlot-led Congress government has been delivering plenty of support of late.

The 2023-24 state budget was much hyped for its slew of welfare measures, but it also reserved a significant slice of the pie for Hindu religious and cultural causes.

One of the proposals in this budget was to open Ved Vidyalayas in 13 districts where these schools do not have a presence yet.

The cited reason was “encouragement and protection” of “Vedic sanskriti”. According to government figures, eight of the existing 26 schools were opened after 2018, when the Gehlot dispensation came to power.

With Rajasthan going to the polls later this year, political analysts believe the state Congress is going on a concerted “Hindu push” to counter the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

“This (Hindu push) is not new in the Rajasthan Congress, but this time it is going the extra mile. It is to counter the BJP’s claim that Congress is not pro-Hindu. In Rajasthan society, it is something that will be appreciated,” says political analyst Suhas Palshikar.

ThePrint visited two Ved Vidyalayas on the outskirts of Jaipur— the Sri Guru Kripa Ved Vidyapeeth at the Pitambara Peeth and the Narvar Ashram Seva Samity Ved Vidyalaya at the famous Sri Khole Hanuman Ji temple — to understand how these schools function, the lives of the students, and the political messaging behind it all.

Also read: Rs 500 gas to free electricity, welfare schemes are doubling as poll ads for Gehlot govt

Gruelling schedules, dreams of being ‘bada pandit’

Discipline is the bedrock of life at a Ved Vidyalaya, where students must juggle a regular academic education with Vedic instruction.

The boys rise at 4.30 in the morning and are ready by 6am for the day’s first recital of the Gayatri Mantra, which takes place at the temples these schools are based out of. Breakfast is served at 6.30am.

Half an hour later, the students head to school, where they study typical subjects such as maths, English, and Hindi.

At 1.30 pm, they return to the ashram for lunch, typically comprising items like upma, dalia, and halwa.

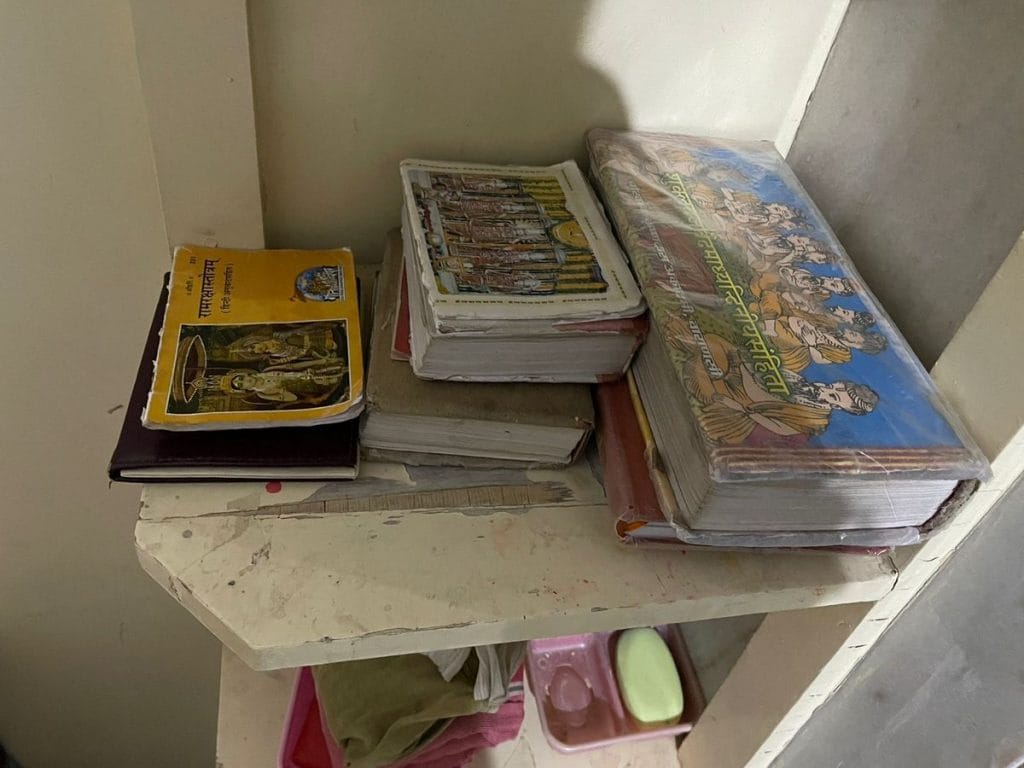

After an hour and a half of rest, their Vedic training begins. For two hours, from 4pm to 6pm, the children are taught the texts of the Shukla Yajurveda, mantras, practices for various rituals, and other skills like astrology.

There’s an hour-long sports period thereafter, before the Gayatri Mantra is recited again in the evening. Dinner is served at 8pm, after which it’s time to complete school homework before the lights go out.

It’s a lot for a child, but many students say their sense of purpose keeps them going.

During ThePrint’s visit to Pitambara Peeth, students dressed in their red-and-yellow uniform recite the Gayatri Mantra. While the younger lot fumble, the older ones seem more in control.

Most of the students come from a low-income background. One of them is 14-year-old Ankush Sharma, who has been at the ashram for a year. His father is a taxi driver.

When asked if he misses home, Ankush says yes, with a shy smile.

“I miss my parents but dheere dheere manage ho jaata hai (slowly we learn to manage). The senior students help us out,” he says.

At Narvar, 12-year-old Ankit Pateria, whose father drives a rickshaw, misses home too.

“I cried when I left home, but if I have to study, I need to do this. Our guruji explained to me that I should adjust. He asked me to see the senior students, who guided us,” says Pateria, dressed in a spotless white dhoti and kurta, the institution’s uniform.

A year since his arrival, Pateria says he has settled in.

“Our schedule is very tiring but we do it. I like studying the Vedas. I want to be a bada pandit (big priest) and, if possible, a Sanskrit teacher too,” he says.

His schoolmate Tushar Sharma, 17, nurtures similar ambitions. In his fifth and final year at the Ved school, he has acquired knowledge of kramkand (Vedic ritualistic practices), memorised mantras, and learnt how to do different kinds of pujas.

“My parents wanted me to do panditayi and I respected their wishes,” he says. “I want to study Sanskrit in college. Hopefully then I’ll become a dharam guru or a Sanskrit teacher.”

Other students are willing to skip college and focus solely on becoming pandits, such as Bhawani Shankar Gautam, who is in his fifth year at Pitambara.

“I’m more interested in my religion and my Sanatana Dharma. My uncle used to be a pandit. After his death, my family wanted me to take up the mantle. My father sent me here. I like living this life,” he says.

How Ved Vidyalayas work

The Ved Vidyalayas, first announced during the Vasundhara Raje-led BJP regime of 2006-07, were set up to promote traditional Vedic education.

Each institution is run by a religious trust that is accredited to the Sanskrit Academy, which comes under the Department of Art & Culture of the Rajasthan government.

The Ved Vidyalayas offer a five-year residential course, and students can enroll only after they have passed Class 5 at a regular school.

Admission is limited to a maximum of 50 students over a period of five years, or 10 students per year.

According to sources in the Sanskrit Academy, preference is given to Brahmin boys, but non-Brahmins are allowed to enroll as well.

“When they enroll, all of them are made to do the janeu (sacred thread) ceremony. After that they become dwij (twice-born),” says a functionary at the academy.

“It’s not necessary that all mahants or priests have to be Brahmin. For example, Vishwamitra was a Kshatriya. But performing the ceremony is mandatory in order to be a student of the Vedas,” he adds.

The schools work on a Public Private Partnership (PPP) model. The religious and spiritual organisations take care of the infrastructure and facilities. The state government, on the other hand, provides a stipend of Rs 500 per month to each student, a monthly salary of Rs 8,000 to teachers, and a monthly miscellaneous allowance of Rs 800 to each school.

“During their time here, the students learn the madhyandina shakha of the Shukla Yajurveda. It has 40 chapters and almost 2,000 mantras. Along with that, they’re trained on how to do yagyas, astrology, and other things,” says Pawan Kumar Sharma, a teacher at Narvar, adding that the students are also mandatorily enrolled at regular schools so that they have modern-day skills too.

“There is a shortage of good pandits in society today. We are creating future pandits. Being a dharam guru is a career option for them. They also can be Sanskrit teachers. These are the kids who will occupy these esteemed positions in the future,” Sharma says.

The children are charged no fees for their five years at the Ved Vidyalayas. During this time, the trust also pays for their regular school education.

‘Saving Sanatana parampara’

The driving purpose of the Ved Vidyalayas is to safeguard Indian culture and preserve Sanatana Dharma, according to Hridyesh Chaturvedi, organisational secretary of the Rajasthan Sanskrit Academy.

“There are about 650 students in Ved Vidyalayas across the state today. It is important to preserve the guru-shishya parampara (teacher-disciple tradition) of the Vedas. For this purpose, the academy created a scheme whereby the new generation can be taken to the Vedas,” he says.

We have a tradition that’s thousands of years old — the Sanatana parampara— and it can only be saved by saving the Vedas,” he explains. “The Vedas are the DNA of Indian culture. If we can’t save the DNA, we won’t be able to save our culture.”

Chaturvedi claims that before the British parliamentarian Lord Macaulay introduced Western-style education during the 1800s, traditional gurukuls were functional in India.

“The country had to accept the English, modern education system due to British rule. But that needs to be changed,” he says.

“Now we see English education as a status symbol. We think that if our kids don’t learn English, they’ll be left behind. It is because of this that the Rajasthan Sanskrit Academy started opening Ved ashrams in the state. We asked religious and spiritual organisations to help us and motivated them. Our society has to be motivated by these organisations,” he adds.

Braj Mohan Sharma, a mahamantri (temple chief) with the Narvar Ashram Seva Samiti, says that he’s involved in the project because “the new generation has gone astray”.

“There are foreign agencies at work in India. You must have seen the instances of conversion. The Christians and minorities want to grow in number and become the majority. That’s why they are taking the new generation in the wrong direction. We should give our kids the education that they need to take care of the culture and religion they are born into,” he says.

“If these kids become capable then I know that Brahmins and pandits can even go abroad and become successful. That’s the message that even Modiji is trying to give,” he adds.

‘Congress is trying social engineering’

Other than the proposal to expand the state’s network of Ved Vidyalayas, the Gehlot government’s 2023-24 budget also pitched a plan to “promote Sanskrit education”. The government announced the setting up of 16 Sanskrit Mahavidyalayas (colleges), with the aim of eventually having one such institution in every district of the state.

According to officials at the Sanskrit Academy, Rs 85 lakh was allotted for setting up the 13 Vedic schools announced in the 2023-24 budget. The Sanskrit Mahavidyalayas, on the other hand, are under the Department of Sanskrit Education (a wing of the Education Department), which has a higher budget for Vedic education.

In addition, development packages, worth Rs 100 crore each, were also announced for three important religious sites — Govind Devji Temple in Jaipur, Pushkar in Ajmer, and Beneshwar Dham in Dungarpur district.

Notably, last October, Gehlot inaugurated what he termed the world’s “tallest” Shiva statue in Rajasthan’s Rajsamand. Yoga guru Ramdev as well as leaders of the BJP were present at the unveiling of the 369-foot statue. During the event, Gehlot claimed that Congress leader Rahul Gandhi was a “Shiva bhakt”.

Taken together, experts say, these developments point to a wider strategy that the Congress has adopted to dislodge the BJP from its position as a “thekedaar” (custodian) of Hinduism. This is especially evident in two other states that will vote at the end of the year— Chhattisgarh, where the Congress is in power, and Madhya Pradesh, currently ruled by the BJP.

While the Chhattisgarh Congress has adopted Ram and the cow as two of its main planks, the Madhya Pradesh Congress has instituted a pujari prakosht (priest cell) and even held a dharm samvaad (religious conference) at its state headquarters earlier this month.

Speaking to ThePrint, Rajasthan Congress leaders seem divided over the efficacy of their strategy, ostensibly aimed at countering the BJP’s Hindu-Muslim polarisation tactics. While some senior leaders argue that the BJP has systematically erased the Congress’s past record of serving the Hindu community, others contend that the BJP’s ideological grip is too strong for the Congress to make a significant dent.

Amid this debate, the Gehlot government has adopted a “governance-centric” approach, prioritising development and public welfare, while also trying its hand at social engineering.

Political analyst Suhas Palshikar, quoted earlier, says that this strategy can only gain traction in places where the Congress has the necessary on-ground organisation — and in Rajasthan, the Gehlot faction does.

“The Hindu population (in Rajasthan) is roughly divided between the two parties. The Congress is doing this only to ensure that the BJP doesn’t make gains by playing on its Hindu identity,” he adds.

Rajasthan-based political analyst Manish Godha also points towards various “boards” that the Gehlot government has set up after coming to power in 2018. Among these is the Vipra Kalyan Board, set up for the welfare of Brahmins.

“We saw this less in the last Congress regime. It’s definitely more in this regime,” says Godha.

“The government has a department for devasthans, which deals with state-aided temples. This specific department has organised a lot of events during this government’s tenure,” he adds.

According to Godha, the Congress is trying to shift the narrative that it is not as “serious” about Hindus as the BJP.

“The Congress is most definitely looking at social engineering. Apart from the Hindu push, they’ve recently also created a board for Sikhs. Before that, there was one for backward castes,” Godha points out. “In the last four or five months, at least four such boards have been made.”

‘What we get from govt is not enough’

Even as the Gehlot government tries to appeal to its Hindu constituencies, whether or not these efforts are perceived as “enough” is up for debate.

In the Ved Vidyalayas, for instance, there is some dissatisfaction about the allocation of government funds.

While the Sanskrit Academy implementing the programme is a part of the government, its officials say the budget for Ved Vidyalayas should be increased.

“What we get from the government is not enough. We, at the Sanskrit Academy, are trying to tell the government that salary for teachers should increase,” says Chaturvedi. “They need to at least be paid minimum wages to have a dignified existence.”

Further, says Chaturvedi, private religious organisations should not have to foot a greater share of the project’s costs than the government.

Teachers, meanwhile, claim that their salaries have not kept up with rising costs.

“We know what the market prices are. We should at least get as much as is required to run our households,” says teacher Pawan Sharma.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also read: Why Sachin Pilot is fighting a losing battle against Ashok Gehlot