Chapter I

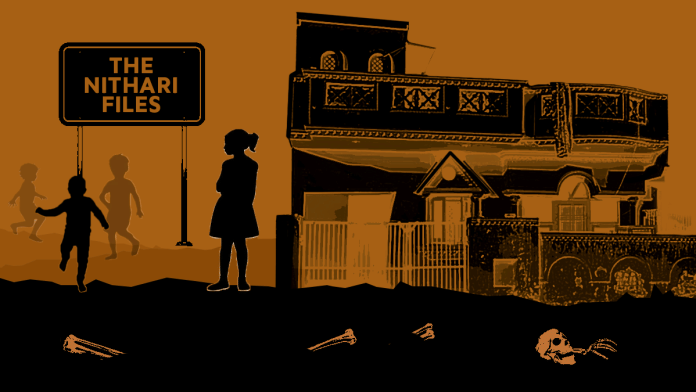

Schools were shut for the summer holidays. The 10-year-old stepped out to get a dupatta stitched—a short walk to the tailor, barely 300 metres from home in Noida’s Nithari village. It was meant to be a routine errand. But she never returned.

She was one of many reported missing from the area between February 2005 and 2006. By the time skulls and other human remains were recovered from a drain outside house no. D-5 in December 2006, reports of missing persons had been coming in for two years, but the Uttar Pradesh police didn’t act.

A probe eventually led the police to D-5, its owner Moninder Singh Pandher and help Surinder Koli. Pandher bought the duplex in February 2004, and hired Koli in July that year.

The first disappearance, court records show, was reported in February the following year. Children playing in the enclosed space behind D-5 found what appeared to be a human hand in a polythene bag. Police were alerted. Eyewitnesses recall them visiting the spot, covering the hand with mud, and assuring residents that “there was nothing to worry” about.

Another year passed before the police finally registered an FIR, and the skeletons came tumbling out.

In search of a job, the Noida resident left home on 7 May 2006 to meet one Mahendra Singh in Sector 31. It turned out to be the last time her family saw her. Her father first approached the Nithari police post, and then landed up at D-5, where he confronted Koli.

The father approached the police again, demanding an FIR be registered under sections for kidnapping and wrongful confinement. Instead, police filed a missing persons complaint. A case was eventually registered, but not before a local court ordered the police to do so. It took another rebuke from the Allahabad High Court for Noida Police to expedite the investigation, and Koli was first “arrested” on the morning of 29 December that year.

Based on his purported confessions, police recovered 15 skulls, clothes and other belongings from the drain outside D-5 that same day. House owner Pandher was also taken into custody.

When she heard about all this, the mother of the 20-year-old rushed to the spot. There, she identified the clothes and slippers of her daughter who went missing three months earlier, on 5 October. Based on the mother’s complaint, Noida Police booked Pandher and Koli in another case.

Another case was registered against Pandher and Koli on the complaint of a couple who filed a missing persons report for information on their daughter, then 14, on 20 July 2005. A DNA test later confirmed their daughter was among the victims.

Less than a month after the recovery of human remains and other “incriminating” material from the drain outside D-5, the case was handed over to the CBI, along with custody of both Pandher and Koli.

Also Read: ‘Murder, cannibalism to attempted necrophilia’ — gory timeline of cases against Nithari accused

Chapter II

The CBI’s case rested on two pillars: Koli’s purported confession, first to an officer of the bureau in January 2007 and then to a judicial magistrate in Delhi in March the same year; and disclosures he made while in custody of UP Police that supposedly led to the recovery of human remains and other materials.

Koli, the CBI alleged, confessed to having raped and killed multiple victims, and disposing of their bodies. The CBI’s theory was that Pandher “cavorted” with sex workers who frequented D-5, and watching them “triggered an automaton state” for Koli, who “enticed the victims on one pretext or the other”, attempted to or raped them, followed by murder.

“He then took their dead bodies to the servant’s bathroom on the upper floor of the House No. D-5, Sector-31, Noida and cut the body parts of the dead victims and eat (sic) some part of torso, and throw the skull and clothes etc., partly in the enclosed space/gallery behind House No. D-5 and discharged rest of the body parts in the drain flowing in front of the house,” the probe agency submitted before the Supreme Court.

The trial court sentenced Koli based on the disclosures, citing them to be “consistent” with all the “evidence and surrounding circumstances”.

But the CBI’s case fell apart as it reached Allahabad HC.

Allahabad HC was apprehensive not just about the authenticity of the confessions but procedures adopted by CBI in recording them. It also bought into the defence’s challenge to the date of Koli’s arrest.

To begin with, Allahabad HC observed an unexplained delay in recording Koli’s confessional statement, despite recoveries made almost immediately after his initial purported disclosures. It noted that, going by the prosecution’s submissions, Koli first ‘confessed’ on 29 December—which led to recoveries from the drain outside D-5—followed by confessions to the police on at least four occasions in January 2007: on the 3rd, 11th, 13th and 18th.

It also took note of CBI’s inability to submit a progress report between 18 January and 1 March, when Koli ‘confessed’ before the magistrate.

The Allahabad HC further questioned CBI’s submission that it needed Koli’s prolonged custody owing to different investigating officers in the 16 other cases in which the house help from D-5 was named as an accused.

It also had doubts about the need to record a confession before a magistrate in Delhi, rather than in Ghaziabad. The CBI had justified its decision by citing the assault on Koli by lawyers on court premises in the days leading up to the recording of the confessional statement. Allahabad HC was quick to point out that the agency produced Koli before a court in Ghaziabad on at least two occasions after the assault by lawyers.

Additionally, Allahabad HC asked CBI to explain how Koli—who gave his consent to the Delhi magistrate in writing—could’ve known his confession would be recorded before a magistrate in Delhi, rather than Ghaziabad.

Koli’s education, up until Class 7, was another factor Allahabad HC took note of, while disapproving of the prosecuting agency’s approach.

It criticised the CBI for failing to provide Koli medical assistance, and the UP Police for not conducting a medical examination during his time in police custody.

Allahabad HC also junked the medical report suggesting no “fresh injuries” on Koli at the time of recording the purported confession before a magistrate. It said the report should have explained the nature, duration and timeline of old injuries, as the court tried to ascertain whether the accused had been subjected to custodial torture.

The team of counsels representing Koli, Yug Mohit Chowdhury among them, also cast aspersions about the date of his arrest. Koli, they argued, was first arrested on 27 December 2006. Allahabad HC observed that the prosecution failed to prove Koli was arrested on 29 December.

Allahabad HC also refused to accept the prosecution’s claim that investigators, led by Kohli’s purported confession, recovered a kitchen knife on 11 January and an axe on 18 January 2007. Recoveries made from premises already under custody of investigators did not stand, it said.

Investigators, it noted, “thoroughly searched” D-5 at least four times—twice before recovery of the knife and thrice before recovery of the axe. It also took note of the testimony of a police officer who said a search was carried out at the exact spot where the axe was later discovered on 18 January.

The incident from February 2005—when Noida police were alerted to the discovery of what appeared to be a human hand in the area surrounding D-5 and chose to downplay it—also returned to haunt the prosecution. The defence counsel cited as proof that the police were aware of human remains being found in the area long before Koli’s purported confession.

Allahabad HC also took exception to how the judicial magistrate continued recording Koli’s confessional statement despite him allegedly revealing he was tortured to confess to two to three victims’ photos. Koli, it said, should’ve been sent for medical examination to assess the authenticity of his claims.

Allegations of torture during confession should have been considered, and the statement rendered “untrustworthy” by virtue of section 24 of the Evidence Act, Allahabad HC said. It also ruled that the magistrate handed over Koli’s custody on the two days just before his statements were to be recorded, thereby not removing the possibility of torture and coercion. These reasons, it argued, were enough to render the confession unreliable.

Also Read: A tale of 2 Nithari verdicts—how same evidence 14 yrs apart led to opposing conclusions

Chapter III

Overall, the Nithari killings led to registration of 16 cases against Surinder Koli. He was convicted and sentenced to death in 13 cases, and acquitted in the remaining three by a Special CBI court in Ghaziabad.

Pandher was acquitted in 10 of these cases, and handed life sentences in two, while one case resulted in his conviction and sentencing under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956. Pandher ultimately walked out of jail on 20 October 2023, following his acquittal in the final case.

Exonerating Koli in 12 cases, the Allahabad HC in its judgment reproduced extracts from the confessional statements made by him before the judicial magistrate: “Ye matlab jab UP police ne jab mereko pakda tha us time mein matlab ki inhone mere ko ye saare photo dekh dekh kar sab ka inka naam wagarah inhone hi hai matlab ki iska ye naam hai, achha! Ye time wagarah ka aur is tarah ka lekin time ka to mere ko abhi pata abhi bhi nahi hai pata, ye bataya tha mai bhool gaya.”

(When UP police arrested me they made me see these photos again and told me the names of those victims. For each photograph, they provided me with the name, the time, the manner, and so on. However, I’m not sure about the time, even now. They had told me all this, but I have forgotten.)

Allahabad HC noted that Koli repeated on at least 18 occasions that he did not recall the exact timeline and other critical details of the alleged crimes.

Nineteen years after he was first arrested, Koli walked out from Greater Noida’s Luksar jail a free man last week.

The one remaining case that had kept him behind bars after his acquittal in the other 12 cases involved the disappearance of a 14-year-old girl who was last seen on 8 February 2005. The family approached the police who brushed aside their concerns, suggesting that she could’ve eloped.

A case was finally registered six months after her disappearance. The breakthrough came more than a year later, when the family heard of human remains being recovered from the house in Noida Sector 31.

Both Pandher and Koli were sentenced to death in this case, which Allahabad HC ratified in September 2009; though it acquitted Pandher citing circumstantial evidence against him. The Supreme Court had upheld Koli’s life sentence in this case in February 2011, only to then acquit him in the case on 11 November, 2025. Upholding the life sentence handed to him in 2011 would, SC said, amount to a “manifest miscarriage of justice”.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

COMMENTS