For decades, India was perceived as the world’s back office, providing services, outsourcing and incremental work. That story is changing fast.

India’s moment in deep tech and space has advanced from a distant promise and is now underway, via satellites, rockets, robots and manufacturing hubs.

It is being further amplified by funding rounds, policy shifts and a new generation of founders. The question is no longer if India can be a global deep tech player and innovate technologically; it is how fast and how well.

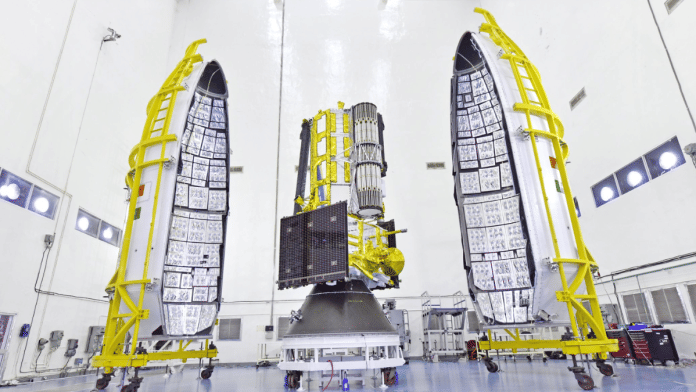

We’ve been on the cusp of this shift at Pixxel, building hyperspectral imaging satellites, collaborating with partners worldwide and navigating regulatory, financial and supply chain challenges. These aren’t abstract hurdles, but the ground truth every deep tech founder must contend with.

And they’re realities every investor, policymaker and end-user must also understand if deep tech is to thrive.

So what does it take to build generational deep tech companies in India?

Here are some of our reflections. It starts with the grit and resilience required to raise capital, navigate complex regulations, and build breakthrough technology, often long before the market is ready.

It also means confronting the ground realities: the hidden gaps in policy, demand, and talent that can quietly stall progress if left unaddressed. And finally, it’s about seizing the moment where India’s talent, cost advantages, and global partnerships converge to create unprecedented opportunity.

Grit and resilience

Every deep tech story begins with friction, magnified manifold in space – unforgiving tech, long timelines and uncertain payoffs far beyond a typical venture cycle.

For Pixxel, the early years weren’t just about getting satellites into orbit but also proving that hyperspectral imaging – the ability to see Earth in hundreds of spectral bands invisible to the human eye – could power a business, not just research.

The purpose was never just prestige, money or valuations. It was the possibility of giving the planet a health monitor and tools that could detect crop stress before famine or before methane leaks, disaster and deforestation become irreversible.

However, the challenges were numerous. Convincing investors that hyperspectral imagery wasn’t a pipe dream took grit. Many wanted quick wins or clear models of return on investment. Raising capital globally meant navigating scepticism about whether deep tech could truly emerge from India.

In addition, building satellites in India meant sourcing components from fragmented global supply chains, improvising around export restrictions and working within a regulatory maze designed when private space companies barely existed. In many cases, Pixxel the first company to be awarded certain exemptions and certifications.

Now, India’s ecosystem needs catalytic public-private capital and smoother onramps for companies at this fragile early stage. Without that, too many good ideas risk burning up before ever reaching orbit.

Ground realities

Amid the momentum gained in India recently, it’s important not to get lost in the headlines. India’s deep tech momentum masks persistent gaps in demand, policy and talent.

In particular, while the government is the largest consumer of space data, demand across ministries and sectors remains fragmented, with most having only procured data from other government ministries, rather than from the private sector.

What’s more, fragmented ministries, uneven execution and thin expertise force startups to lean on global markets before domestic ones mature.

For instance, agriculture ministries may run their own remote sensing programmes, while energy or disaster management agencies procure separately, leading to duplication, inefficiency and missed opportunities for scale.

On policy, progress can be seen with the establishment of the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe), faster licensing and a new space policy that finally acknowledges private participation.

Beyond the space economy, India’s satellites and analytics are already contributing to the climate-tech ecosystem, helping to predict crop yields, monitor methane emissions and model biodiversity loss.

As the world now tilts towards juggling both multilateralism and sovereign inshoring, India can leverage regional alliances, such as the Indo-Pacific centred Quad, BRICS (the alliance of major and emerging economies) and South Asian network SAARC, to sell hardware and data and co-shape global space and sustainability frameworks.

Looking ahead, India shouldn’t just follow a map, but become the cartographer. India’s space industry has the scale, talent and cost advantages that give it the chance not only to participate in this global race but also to set its own terms.

The lines we draw today will decide whether we are remembered as passengers in space, or as the ones who redrew the constellations ourselves.

This article is republished from the World Economic Forum under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.