Bengaluru: For the first time in 22 years, the majestic Asiatic elephant Arjuna will not be part of the annual Dasara procession outside the royal palace in Mysuru on 12 October. Aged around 64, Arjuna died last year during an elephant capture operation to translocate and radio collar “rogue” tuskers.

Even though his death still rings loud in the heart of the city weeks ahead of the festival, the Karnataka forest department continues to use capture operations to resolve human-elephant conflict and is now willing to revive an even older, outdated and banned method—khedda.

In Mysuru, the familiar debate between tradition and torture is playing out. It’s not very different from Tamil Nadu’s Jallikattu battle between folk rituals and animal rights groups.

From 2012 to 2020, Arjuna, a resident of the Balle Elephant Camp in Kabini, carried the golden howdah (a covered seat) weighing 750 kg with the idol of goddess Chamundeshwari during the festive Mysuru Dasara processions. The grand tusker had retired from capture operations—but was roped in by the forest department to catch a wild elephant.

The practice, which the department has been following since the 1980s, involves a team of mahouts (experienced elephant handlers), veterinarians, and trackers using tamed elephants to capture “aggressive” and “rogue” elephants. Conservationists and experts are critical of this capture method due to multiple mishaps.

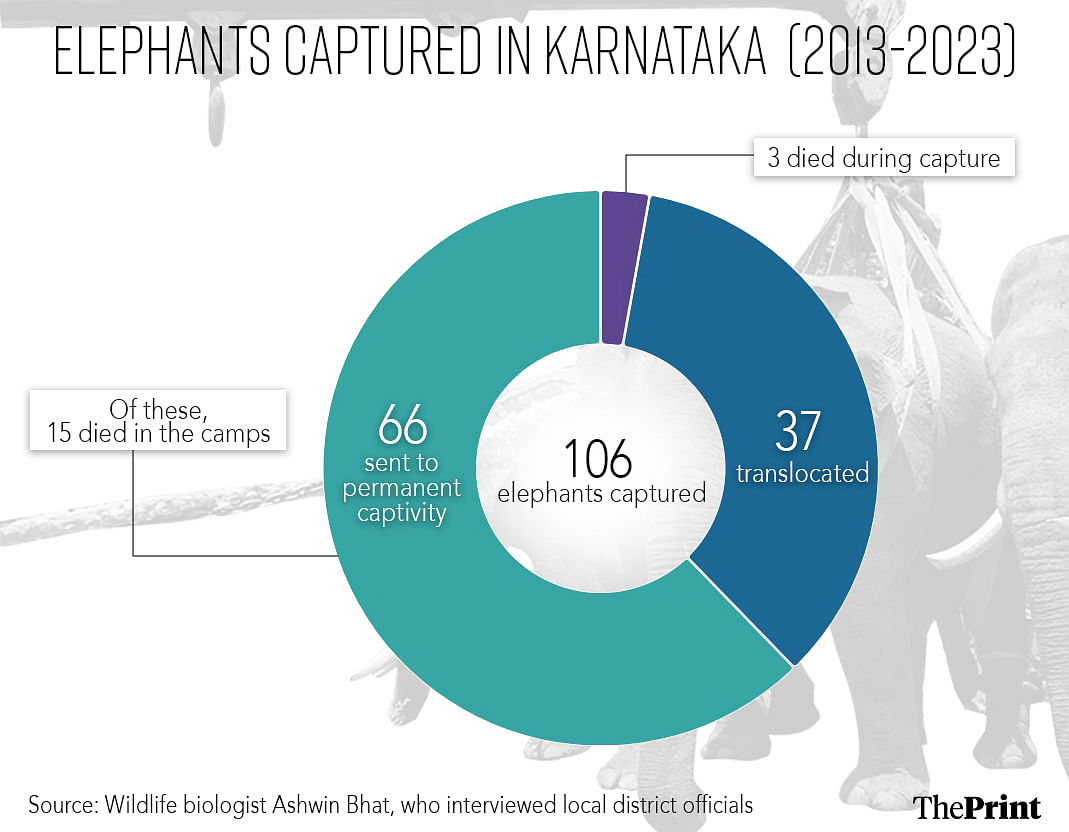

“In 2023 alone, three elephants succumbed to death during the capture of wild elephants. These botched-up captures go unquestioned and emboldened by this, the Karnataka government continues on this path of capturing wild elephants with impunity,” a statement issued by the Centre for Research on Animal Rights (CRAR) said.

Arjuna died in a similar operation in December 2023. He was well-known and overly loved by the people of Mysuru. “It feels strange,” said Vivek, one of the workers within the Mysore Palace who was preparing the elephants for a bath, “to not see Arjuna here with the other elephants. People used to throng the palace to get a glimpse of him.”

Subsequent public outcry prompted the forest department to release a standard operating procedure (SOP) in August 2024 regarding elephant capture operations. However, wildlife activists are still wary about the state’s reliance on using capture operations to mitigate human-elephant conflict.

Elephant capture operations to appease local populations are a smokescreen, a false reassurance that does not address root causes issues. They are expensive, hugely risky, and add a permanent cost of elephant upkeep on the exchequer.

—Bharati Ramachandran, CEO of Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations

Problem with capture operations

This year, 59-year-old Abhimanyu will carry the howdah for the fourth and final time. After he retires, the mantle will be picked up by another elephant, most likely one captured in a bid to mitigate human-elephant conflict.

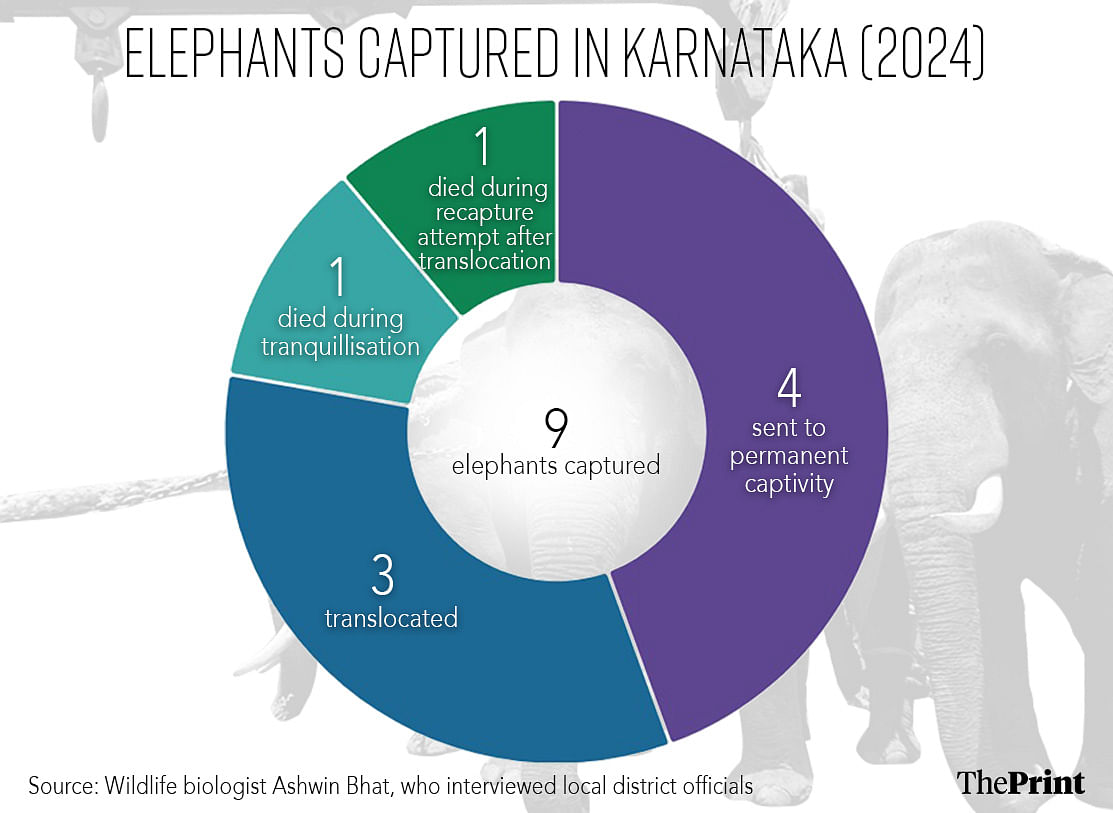

Since 2013, the Karnataka Forest Department has captured 115 elephants, according to data collected by Ashwin Bhat, a wildlife biologist who works at the Wildlife Research and Training Centre in Kali Tiger Reserve, Uttara Kannada district. Although Karnataka doesn’t have data on the number of elephants killed in such operations, Bhat estimates it could be around 20: four during capture attempts, one during tranquillisation, and 15 in relocation camps.

The capture operation Arjuna died in was undertaken after several wild elephants were spotted near Yeslur by the forest department, which installed radio collars to track their movement. When the team of four ‘tamed’ elephants and forest staff moved in to capture the wild ones, the enraged elephants attacked them. While three elephants and the staff fled, Arjuna stood his ground.

“Arjuna was retired from any such combing operations four years before this incident,” said Ramesh Belagere, wildlife activist and managing trustee of the Foundation for Ecology and Education Development (FEED).

As per the “Guidelines for care and management of captive elephants” released by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of India (MoEFCC), retired elephants should only be put to light work and must be under the constant supervision of an experienced veterinarian.

“Hence it is an open and shut case when it comes to deciding whose fault it is,” Belagere added.

Wildlife activists have documented multiple botched elephant capture operations over the past few years. In January 2023, a partially blind 20-year-old wild elephant fell 10 metres to his death in a coffee-drying yard when a tranquillising attempt failed to fully sedate him. Later, a wild tusker in Mudigere of Chikmagalur district who had been previously captured, was wrongly tranquillised during translocation, leading to his death.

Several scientific studies have demonstrated that capture and translocation operations are ineffective in mitigating human-elephant conflicts. One such study, conducted by the Bengaluru-based Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre (WRRC), revealed that elephant camps in Karnataka, on average, were located 130 metres from a forest. Although 66 per cent of the camps were located in and along the periphery of forests, many of them were at a 2-kilometre distance from a river—an important part of elephant habitat.

Belagere explained how several elephants he observed in captivity displayed signs of obesity, arthritis, and even tuberculosis. “Capture and post-capture conditions break the spirit of the elephant because you are taking them away from their natural habitat,” he said. Many captive elephants display signs of aggression and distress post-capture, he added.

One such incident was noted in 2018. Leaked footage from the elephants’ training ground in Mysuru showed an elephant swaying continuously, indicating psychological distress, activists said. More recently, on 20 September, a video emerged showing two Mysuru Dasara jumbos, Dhananjaya and Kanjan, knocking down barricades and fighting in Mysore Palace.

“The fight, which happened during their feeding time, was halted right outside the palace grounds, preventing a dangerous situation,” said Prabhu Gowda, deputy conservator of forest (Mysuru wildlife division) who is part of the Dasara executive committee.

Due to the incident, the public will not be allowed to see the elephants prior to the procession, Gowda said. Moreover, Karnataka Forest & Environment Minister Eshwar Khandre warned officials not to allow photoshoots or videography featuring the Dasara elephants.

However, both these incidents prompted calls from activists to stop the use of elephants for religious festivals.

No matter how well-trained, the elephants are required to adjust to the sounds of firecrackers as well as the sights and smells of human activity. They also have to prepare for the massive weights they would carry every year for the festival. When they are not practising for the procession, the jumbos are chained by their legs, preventing them from roaming around with their herd.

A study conducted in 2019 showed that the elephants from the Mysuru Dasara camp exhibit a higher amount of stress hormones than others. Such heightened stress levels can cause infertility, hyperglycemia, suppression of immune response, imperfect wound healing, and neuronal cell death, the study said.

tusks. She was eventually moved to a rescue centre | Photo: Ramesh Belagere, by special arrangement

Following the death of Arjuna, the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Karnataka High Court to stop the practice of capturing elephants.

“Elephant capture operations to appease local populations are a smokescreen, a false reassurance that does not address root causes issues. They are expensive, hugely risky, and add a permanent cost of elephant upkeep on the exchequer,” said Bharati Ramachandran, CEO of FIAPO. Meanwhile, post-capture, other elephants take over the space of captured elephants, “keeping a dangerous cycle of fear and unnecessary violence alive,” she added.

Karnataka forest officials maintained that they resort to capture operations only when it is “absolutely necessary”. “These decisions of capture are dynamic. We assess the situation and, if only as a last resort, take up capture,” said R Manoj, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Project Elephant).

Also read: Unions are getting a boost in Bengaluru tech industry. Byju’s layoffs was a catalyst

Pushback against fresh guidelines

Even after Arjuna’s death, Karnataka did not stop elephant capture operations. The forest department instead formed a committee to probe the causes behind the mishap. Although the report hasn’t been made public, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah, Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar, and Forest Minister Khandre released a detailed SOP for the capture of Asian elephants in August, based on the findings from the committee’s investigation. However, activists argue that the guidelines merely provided a veneer of reform without addressing the root of the problem.

“This [SOP] is only to justify the captures, which are only going to increase unless a court order stops them,” Bhat said. Although a protocol was necessary, “the state, rather than phasing out the conflict, is promoting it,” he added.

Other activists are concerned about how the state can bypass regulations by exploiting loopholes. For example, one such guideline within the SOP requires all elephants in the capture operation to be below the age of 60 “unless specifically permitted by the Chief Wildlife Warden (CWLW).”

“We saw what happened with Arjuna—he was retired and yet put through strenuous activities,” said Belagere. He recommended that once an elephant is retired, it shouldn’t be used for such operations. “It should be a strict and closed rule.”

But some voices within the wildlife community favour capture and translocation operations.

“Elephants are dangerous animals. We can’t be living with such species,” said Colonel Cheppudira P Muthanna (Retd), former president of Coorg Wildlife Society. He recalled an incident where he was attacked by an elephant that was 45 metres away.

Demanding that all elephant species be translocated, Muthanna added, “There is no point in capturing elephants after they have caused damage. Action should be taken now.”

According to data from the Karnataka forest department, 148 people have died as a result of elephant encounters in the state over the last five years.

“The character and severity of the conflict varies across districts and is a major concern in the hilly parts of Hassan, where 72 people have died in the past 21 years,” said Ramachandran. But she attributed this increase in the human-elephant conflict to restrictions imposed on the movement of elephants and human encroachment on their habitat as a result of various developmental activities.

Earlier, elephants used to be scared of humans, but now with increasing human encroachment into elephant habitats, the animal has now gotten used to humans. There is no fear.

—Ramesh Belagere, managing trustee of the Foundation for Ecology and Education Development

According to a report by Wildlife Trust of India, South India has 28 corridors that are essential for the movement of its 14,612 elephants between protected areas. But with the increasing proliferation of private establishments like coffee estates and homestays, several elephant corridors are being blocked. Wildlife experts have called out the increasing infrastructure activities in animal habitats such as rapid highway work, rock breaking, retaining wall construction, and land levelling.

“Earlier, elephants used to be scared of humans, but now with increasing human encroachment into elephant habitats, the animal has now gotten used to humans. There is no fear,” Belagere explained.

A 2021 study on Asian elephants showed that translocation is the primary strategy for mitigating human-elephant conflict in India, with over 600 elephants translocated since 1974. However, the human-dominated landscapes where human-elephant conflicts unfold “are prime elephant habitat, and not merely marginal areas that elephants use in the absence of other options.”

“So how can the animal be blamed?” said Belagere.

Also read: Patiala RGNUL students want V-C resignation at all costs. They won’t have their voices muzzled

Calls to revive khedda

Even as criticism continues to mount over elephant capture operations, during the International Conference on Human-Elephant Conflict Management last month, Deputy CM Shivakumar urged forest department officials to restart the banned khedda operation.

The older capture method of khedda involved driving elephants toward deep, camouflaged ditches. Once they fell into the ditch, the elephants would be starved so they could be tamed more easily. Multiple reports suggest that elephants sustained injuries in such operations.

“Each captive elephant is trained through brutal beatings, starvation, and isolation, all aimed at breaking the spirit of the animal until it is a broken shadow of its wild self. The ‘kraal’ is this horrific enclosure in which such captured elephants are kept isolated for ‘training’,” Ramachandran explained.

At least 36 khedda operations were held between 1873 and 1971, after which it was banned under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 as it was considered crude, gruesome torture perpetrated on animals.

Arjuna was among the last of a generation of elephants that were captured during the 1968 khedda operations. “The trauma of his capture stayed with him until he breathed his last,” Belagere remarked. “He was put through so much that he stopped understanding what fear meant. He never backed off against any animal or human standing opposite him. Even in his final fight, he didn’t back off.”

The state now plans to restart khedda amid rising human-elephant conflicts. “I was showing a video clip to the chief minister [Siddaramaiah]. In my village, adjacent to my house, more than 50 elephants were walking on the border of my house. My mother and family members stay there. We know the difficulty of the situation,” Shivakumar said at the conference, while explaining why khedda should be revisited.

Back at the Mysore Palace, 14 elephants—Abhimanyu (59), Dhananjaya (33), Mahendra (41), Bheema (24), Gopi (42), Prashantha (51), Sugreeva (42), Kanjan (25), Rohit (22), Ekalavya (39), Varalakshmi (68), Lakshmi (23), Doddaharave Lakshmi (53), and Hiranya (47)—are camping and rehearsing for the Vijayadashami procession, along with their caretakers, mahouts, and kavadis.

Abhimanyu, the heaviest of all the Dasara elephants, weighing 5,560 kilograms, started training early in September, carrying a wooden howdah with a weight equivalent to that of the golden howdah. In 2013, the Karnataka High Court-appointed elephant task force prepared a detailed report, urging the state government to replace the 750-kilogram howdah with a lighter replica or to have the idol be carried on a chariot drawn by elephants, among other recommendations.

The court eventually left it to the wisdom of the state government to decide on how best to use and protect elephants during festivals. However, the state has maintained that there has been no violation in the use of elephants for Dasara procession and hence, has not implemented any of the task force’s recommendations.

As the royal city prepares to welcome a sea of visitors and tourists for the vibrant celebrations of Mysuru Dasara, pressing questions remain to be addressed about the treatment of the majestic elephants that are caught between the demands of culture and survival.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)