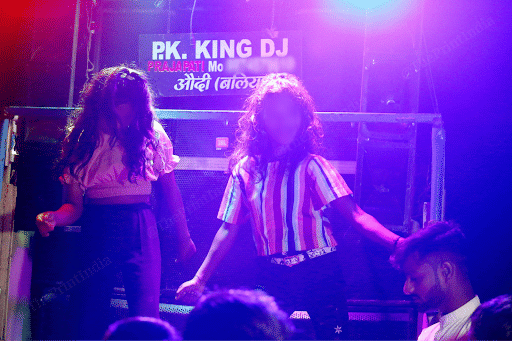

Karishma, Mahi, and Nimmi are the star dancers at a wedding in a village in Uttar Pradesh. Men have waited for days for their arrival, having paid a whopping Rs 20,000 for the raunchy nighttime performance. However, the dancers are far from getting VIP treatment. They are crammed like goats into the back of a pickup truck en route to the venue. Chewing tobacco and gripping the railings, they jostle along Gonda’s bumpy roads, crying out each time the truck hits a pothole.

“Drink less and drive carefully over the bumps! I don’t want to die. I’m not Sapna Chaudhary yet,” yells 35-year-old Karishma at the driver. He continues to croon Bhojpuri songs—Sway, sway, on Holi your youthful charm; She won’t agree, but we’ll colour her rosy cheeks—while sipping alcohol and driving recklessly.

Her reference to Chaudhary, the Haryana dancer-turned-Bigg Boss contestant, elicits laughter from the group as she spits out tobacco. Chaudhary is a role model for nearly every “orchestra dancer” in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

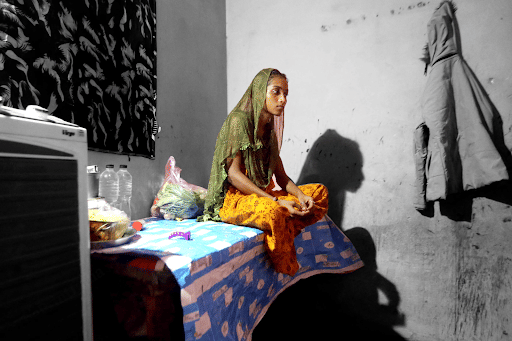

When they arrive at the remote village venue, the trio rushes to a dingy, dimly lit changing room. Using water from a rusty bucket, they wash their faces, hurriedly apply bright red lipstick, slip into glittering lehengas, dab on foundation, and whip their hair loose in one swift motion.

Outside, men queue up to catch a glimpse of them. Children peek through cracks in the windows, and impatient young boys knock on the door, asking how long they will take to get ready. Under the faint yellow light of a precariously dangling bulb, the trio transforms into nothing short of stars—the prime objects of rural male fantasy.

“For them, I am no less than Alia Bhatt tonight,” says Mahi, a 23-year-old dancer dressed in a bright orange lehenga.

From weddings to birthdays to even funerals, men in these villages share one common desire: bawdy performances by orchestra dancers who sway, thrust, and twerk on stage.

The bigger the dancer’s name, the greater the prestige for the village. Meanwhile, wives, daughters, and mothers stay indoors as the men roar in ecstasy, record videos on their phones, demand repeat performances of raunchy moves, and sometimes even attempt to touch the dancers. Guns are handed to the performers as props, and requests for sexual favours—though frowned upon—are hurled occasionally.

Over the years, these male-only entertainment spaces have gradually overshadowed traditional family celebrations. The growing reach of Bhojpuri music, coupled with smartphones, YouTube, and Instagram, has fuelled this cultural shift. Men, accustomed to accessing pornography on their phones, now seek face-to-face interactions with women in these performances.

This socially sanctioned sleaze has eroded traditional family activities, allowing men to dominate and stage these events with tacit support from police, politicians, and peers.

A tradition transformed

The tradition of women dancing at weddings traces back to janwasa—a temporary lodging for the groom’s relatives, or baraat, explains Ajay Kumar Yadav, a political science fellow at Jawaharlal Nehru University. The bride’s family would welcome the groom’s party with performances by traditional dancers. Initially, men dressed as women performed these dances in a practice known as launda naach, a popular tradition in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

“By the 1980s, women began to enter this space, and by the 2000s, with the rise of Bhojpuri cinema, their participation became entrenched and normalised,” says Yadav. “Traditional performances, however, have since been replaced by vulgar dances, with women from West Bengal, Nepal, Jharkhand, and Odisha joining these orchestra companies.”

In the rural heartlands of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, the true heroines of after-dark festivities are performers like Karishma, Madhu, and the underage Bulbul.

Doctor daughter dream

At a wedding celebration in a small village in eastern UP’s Gonda district, an all-male audience cheers and whistles as Karishma thrusts her chest and sways her hips to a popular Bhojpuri song: “With that red lipstick, everyone’s heart races when they see you. You’re the queen of the evening, girl.”

Some men film her performance on their phones, while others shout “chhamiya” and a few leap onto the stage to grab her. The DJ quickly intervenes, announcing into the mic, “Don’t touch the women. If you do, we’ll stop the dance.”

Karishma and the two dancers on stage continue their routine, unfazed. The men retreat, chastened for the moment, though it won’t be long before another group tests the boundaries. A few toss Rs 50 notes onto the stage.

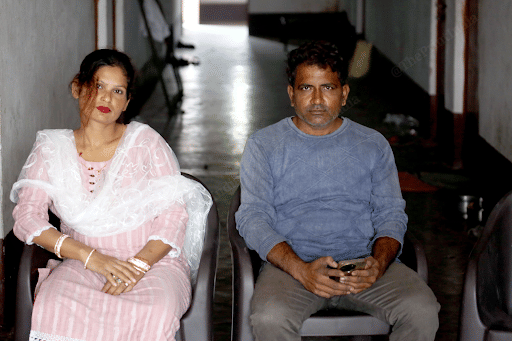

Karishma’s husband, Pinku, weaves through the crowd, pushing past men with his eyes locked on the scattered cash. He scrambles to collect the notes from the dusty ground and retreats to a corner near the stage. The performance, initially scheduled for three hours, stretches to five as the crowd demands encore after encore.

“They pay for three hours, but then they keep asking for more. If we don’t comply, they won’t pay the full amount,” Pinku says, pocketing another note. By 4 am, he has collected Rs 3,000 in tips, on top of the Rs 2,000 booking fee.

The couple returns to their cramped, rented room—once a shop, now fitted with shutters and a curtain for doors.

Karishma, footsore and exhausted, collapses onto the floor. She’s been dancing since she was 12, the year she married Pinku, who was 22 at the time.

“Dancing was his idea,” she says, pulling a wad of notes from her blouse after Pinku steps outside. She had quietly stashed the money before he could grab it.

“He drinks all day, doesn’t work, and joins me at night for the performances. He lives off my money—and so do our two kids,” she says, applying moisturiser to her arms.

The couple’s children, who live with relatives in Lucknow, know nothing of their mother’s profession. Karishma’s earnings, around Rs 20,000 a month, rarely reach her in full. Still, she manages to save a small amount in secret.

“It’s for my daughter. I want her to become a doctor,” she says. Without a bank account, she hides the money in a trunk beneath her glittery costumes, securing it with a key only she has.

Karishma knows her time on stage is limited. She tells people she’s 25, though she’s actually closer to 35. When two potential clients arrive to book her for a show, she quickly applies foundation to lighten her skin.

“I have to look younger,” she says. The men sit on a cot, watching her critically. Before negotiating with Pinku, they insist that she dance for them. Karishma obliges, swaying her hips, running her fingers through her hair, and winking—enough to seal the deal.

As the men leave, they tease her, pinch her cheeks, and ask her to wear more revealing clothes for the performance.

In her rare free moments, Karishma scrolls through reels of Sapna Chaudhary, her idol, while contemplating her own fleeting prime. She is terrified of gaining weight like Chaudhary, and sticks to a strict diet.

“I’m not famous like Sapna Chaudhary. I can only dance until I am 40 or 45—after that, my beauty will fade,” she says.

But Karishma has one more goal: to become a malkin and own her own dance troupe. She has watched other women—wives of alcoholics, mothers abandoned by their husbands—climb the perilous ladder to the top.

“I just need to hold on a little longer.”

A business like any other

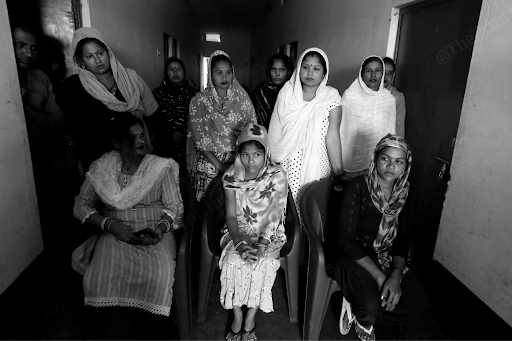

After 15 years as a dancer, 45-year-old Savera is now the proud owner of her own dance troupe, Savera Musical Orchestra, based in Sohnag Bazaar in Deoria, about 200 km from Gonda. Her troupe, which has six to eight performers, is fully booked this wedding season—from November to February.

Savera is a shrewd negotiator. “Let me tell you, I won’t take anything less than Rs 25,000 for three dancers,” she tells three men who approach her for a booking. “I have the best and most beautiful dancers in Deoria.”

When the men demand to see the women in person, she firmly refuses. “You haven’t come here for prostitution but to book dancers. I can show you their dance on my phone.”

Of the Rs 25,000 she charges, only part of it remains with Savera. The DJ costs Rs 6,000, the dancers get Rs 2,000 each, and van rental and driver set her back another Rs 2,000.

The orchestra troupe business has become an integral part of the rural economy in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. This seasonal industry thrives during the wedding months, creating a wide range of jobs. Beyond the dancers, there are drivers, bouncers, light operators, DJs, and vendors supplying costumes and tailoring services. For many, it’s a lifeline.

Savera’s profit, on paper, can go up to Rs 8,000 per booking, but the reality is different. “Clients never pay the full amount. They always try to cut a few thousand, claiming the performance wasn’t good enough or the girls weren’t pretty enough,” she says.

Savera’s journey began 30 years ago when she moved from her village in West Bengal to Uttar Pradesh. Initially, she worked as a domestic helper, earning just Rs 3,000-4,000 a month. “I have no regrets leaving that life,” she says. Her husband abandoned her long ago, but she speaks without bitterness.

“Today, I’m a businesswoman. I create jobs for other women in my community,” she says with pride. Most of her performers are also from West Bengal but have adapted to their new environment by learning Bhojpuri and staying updated with the latest songs.

She points to a tall woman in a maroon dress standing nearby. “This is Fatima Khatoon,” Savera says. “She joined us last year after her husband left her for another woman, leaving her and her daughter with nothing. She was on the verge of begging.”

Thanks to the troupe, Khatoon now earns enough to support her daughter back in Bengal. “Look, she even bought an iPhone 15 and paid the full amount upfront—no EMI,” Savera adds with a smile, urging Khatoon to show off her phone.

But Savera dreams of a different life for her own daughter, who is now 23 years old. Pulling out her smartphone, she scrolls through photos with pride. “Look at her,” she says. “Can anyone say she’s a dancer’s daughter? She looks like a rich woman with class.”

Her daughter, who runs a tailoring shop, has carved out a life of independence and respect. “That’s my real success,” Savera says.

Abuse, assault, apathy

If she could afford it, Savera would hire two bodyguards to protect the women who live in one of the rooms of her two-room office. The abduction and rape of two dancers by eight men, just 38 km from Deoria, has shaken her—and the community of orchestra dancers across Uttar Pradesh.

Rakhi, the owner of an orchestra troupe in Kushinagar, recalls receiving a call at 11 pm requesting two dancers. She refused outright, stating that she never sends her performers out so late.

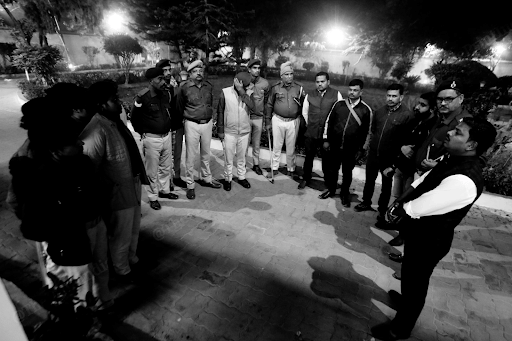

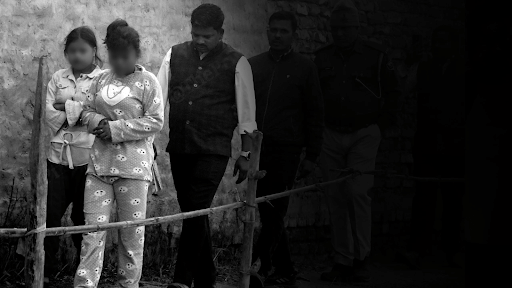

On the night of 8 September, three white Fortuners screeched to a halt outside a modest cemented house. Four men jumped out, fired shots into the air, barged inside, kicked down the bedroom door, and abducted two young dancers at gunpoint.

The women were forced into the cars, taken to a private party, and coerced into performing. According to the FIR, they were molested by the guests and later gang raped by the men who abducted her.

The harrowing details in the FIR describe the men’s comments as they bragged about their intentions: “The girls are great, our night will be amazing. We will make these girls dance at gunpoint through the night.”

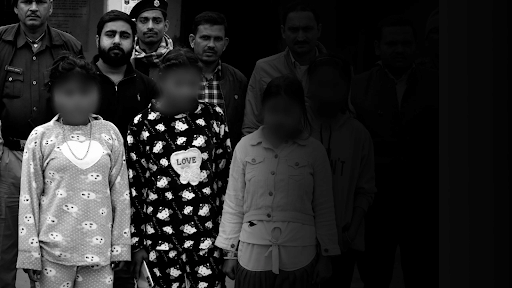

The victims were rescued hours later from a house 10 km away from their rented accommodation. The incident has sparked widespread fear among orchestra dancers in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, prompting some women to carry knives or pepper spray for protection.

Savera relies on DJs and the police helpline for safety but alleges that help rarely arrives in time.

“The police constables who do come say they can’t help because my girls are not locals,” she says. Other dancers and troupe owners echo this sentiment, and complain of police apathy. “They say we’re ‘asking for it’ because of our profession,” one dancer said.

According to these women, police assistance is often dismissive. Calls to emergency helplines are met with remarks like, “We don’t deal with women from outside.”

However, the Superintendent of Police of an eastern UP district refuted these claims. “It’s not about being from UP or outside. We have helped women whenever needed, as they are equal citizens of this country,” the officer said, citing the Kushinagar case as an example. “The police successfully rescued the minor girls within two hours and arrested all the accused. A chargesheet has also been filed.”

A mid-level police officer, speaking anonymously, said they can’t do much.

“These women are themselves dancing and allowing men to touch them. This culture has to end. Otherwise, such incidents will be a daily occurrence. Politicians must move away from vote-bank politics and really work on [improving] social sensibilities.”

The incident has left many dancers questioning their safety. Sonali, a performer from Kushinagar, recalls an incident in 2022 when a man jumped onto the stage at a party in Balia and forced her to dance at gunpoint.

“I thought it was a toy pistol,” she says. “But when he handed it to me, I couldn’t hold it—it was so heavy that it fell from my hand. I ran away.”

Fearing for her life, Sonali left Balia and moved to Kushinagar, believing it to be safer. But the September abductions and gang rape have shattered her sense of security once again.

Fear and freedom

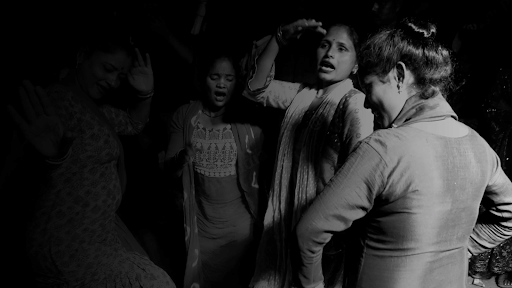

Most of the orchestra women, from veterans like Karishma to malkins like Savera, love and loathe the stage equally. The adulation they receive is often tainted by an undercurrent of violence. Men shove their phones in the dancers’ faces to show pornographic clips, grow aggressive when warned against groping, and harbour an unspoken expectation of sex.

One dancer recalls how a man began masturbating while staring at her during a performance. When she objected, the wedding guests turned hostile.

“They told me, ‘Stop talking so much. Just dance quietly. We will do whatever we want,’” she says, crying. Her fellow dancers surround her in a group hug. “We have to be there for each other,” one of them murmurs.

But no matter what happens, the show must go on.

Rupa, a 24-year-old dancer from West Bengal, remembers the night she broke down mid-performance. A man had forced his way onto the stage, insisting she watch a porn clip on his phone. Furious, she slapped him and chased him off the stage. Instead of support, her orchestra owner screamed at her for “ruining the show”.

“If you want to be in this profession, you’ll have to face this. Otherwise, go back to Bengal. Don’t ruin my reputation in the market,” he warned.

Rupa chose to stay, endure the harassment, and make a name for herself.

Nine years later, she’s the “Madhuri Dixit of Deoria,” commanding Rs 5,000 for a single dance. Men travel from distant villages just to see her perform, while her fellow dancers imitate her moves.

“Rupa is so much in demand that when she’s unavailable, customers start fighting with us,” says Lallu, the orchestra owner she works for.

On stage, Rupa knows how to handle unruly fans. When men jump toward her, she smiles, pushes them away, or turns her head. “I just keep on dancing,” she says with a shrug.

For Rupa, this life is non-negotiable. It offers her a freedom she never imagined back in West Bengal, where she would have been rolling chapatis under her mother-in-law’s thumb.

“This is my identity, one I’ve built with years of hard work,” she says.

When she first came to Deoria, Rupa struggled to lip-sync Bhojpuri songs and couldn’t understand Hindi. She took help from fellow Bengali dancers, spending an hour every day learning the language and watching Bhojpuri songs and Hindi serials.

“If you can’t speak Hindi or Bhojpuri, it’s difficult to survive here,” she explains.

Four years ago, she married the son of an orchestra owner, a taxi driver. He now insists she give up dancing and settle with his family in their village. Rupa won’t have it.

“I’ll leave him before I leave the orchestra,” she says angrily. “What will I do in the village? Make rotis and live in the kitchen?”

Her biggest fear is losing the independence she has fought so hard for. “Here, I’m financially independent and can do what I like,” she says, applying a multani mitti paste to her face.

Rupa dreams big. “I want to be Uttar Pradesh’s Nora Fatehi,” she says, referring to the Canadian dancer renowned for her moves in Bollywood.

Rivalry within

When Rupa joined the orchestra, she was made to sign a strict non-compete agreement to prevent poaching by rival troupes. One clause read: “If I am not available for dance without any reason, and if I go to a different orchestra party, I will be liable to pay Rs 80,000 to the owner.”

Owners go to great lengths to keep their star performers loyal. Popular dancers are sometimes locked in rooms to prevent them from leaving, and during performances, an owner’s confidante watches the dancers closely to ensure they don’t interact with members of competing troupes.

On stage, competition is fierce. Dancers shove each other to grab the money thrown by the audience—all while not missing a step. Rivalries don’t end there; there are divisions among groups: transgender dancers versus women, “outsiders” from Bengal, Nepal, Odisha, and Jharkhand versus local dancers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and women versus minors.

Soni, 36, a dancer from Hardoi, refuses to perform alongside women from other states. “I am a traditional dancer. My entire family has been into dancing, and I can’t stoop to vulgarity,” she says. Soni accuses women from Bengal, Nepal, and Jharkhand of ruining the dance culture by wearing revealing outfits and performing provocative routines.

This fear of “outsiders” taking jobs has fuelled a growing movement to boycott orchestra companies that employ them. Meanwhile, transgender dancers have become increasingly popular, adding another layer of complexity to the competition.

“We don’t object to men being more free with us, getting handsy. Female dancers can’t do that. So, obviously, we are in demand,” laughs Soni, who recently underwent gender reassignment surgery in Delhi.

Savera, watching from her office across the street from a transgender-run orchestra group, expresses frustration. “These transgenders have taken over our profession. All day, I sit on my bed, watching customers go to them. Even when I call out to them, they ignore me.”

According to political science scholar Ajay Kumar Yadav, this trend isn’t new. “In the 19th century, kings and landlords had tawaifs perform for them. Ordinary people, who couldn’t afford tawaifs, hired men dressed as women. There were several popular launda dancers like Chai Ojha and Ramchandra Manjhi,” Yadav said, referencing his research on dance culture in Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh.

Yet, the most sought-after dancers remain young girls.

As young as 12

In a small village in Bihar’s Siwan district, 35-year-old Madhu is desperately trying to ‘rescue’ her 13-year-old daughter—from the authorities. Bulbul, a young Instagram sensation with lakhs of followers, was rescued in a midnight raid by the police from the orchestra company she worked for.

Bulbul’s rise to fame was meteoric. With her signature high ponytail, bold red lipstick, and candid persona, she amassed a small army of admirers across India’s heartland. Young boys and men would flock to her performances to click selfies with her. Her popularity translated into media attention, with frequent interviews where she spoke out about the darker realities of the dancing world.

“Men would offer me Rs 500 to take me into a corner,” she revealed in one viral video. In another interview, when asked why she entered this line of work so young, she blunt replied: “Majboori ba! (It’s a compulsion).”

From earning Rs 1,500 per performance, Bulbul soon commanded up to Rs 5,000, becoming the highest-paid dancer in Siwan. But her growing fame also brought unwanted attention—an NGO contacted the local police to help rescue her.

When officers arrived at her rented accommodation, Bulbul was found hiding under a bed. A female constable coaxed her out, and since then, the minor has been living in a shelter home in Siwan, with only her mother allowed to visit her.

Orchestra owners admit that customers often reject women over the age of 30 and specifically demand younger dancers.

“Families in desperate situations are targeted with promises of money and fame. Once recruited, the girls are locked away after performances to prevent their escape,” said Virender Singh, director of Mission Mukti Foundation, which was involved in Bulbul’s rescue.

“We’ve handled numerous cases where young girls were gang-raped or called us directly, pleading for rescue.”

For Madhu, Bulbul is more than just her daughter; she’s the family’s sole breadwinner. Madhu, herself a former dancer, introduced her child to the orchestra world after her husband abandoned them. She taught Bulbul everything she knew—how to dance, evade predatory men, and ignore lewd remarks.

“It wasn’t a choice but a decision made out of poverty,” Madhu says, cradling a toddler in her arms. Now, she desperately pleads for her daughter’s release. “I promise I’ll never let her dance again. We will go back to West Bengal,” she says.

Bulbul’s performances often reflected the gritty realities of her profession. In one widely shared video, she’s dressed in a bright orange blouse and skirt, making suggestive gestures in sync with the lyrics of the Bhojpuri song she’s dancing to: “I get bad dreams at night because I am not fully satisfied.”

Desperate to escape

At a wedding in Ballia, young girls as young as 12 perform dances on the back of a pickup truck. Shivani, 25, watching from a distance, is filled with growing anger as her father and elder brother join the celebration.

“We had a huge fight because I didn’t want my father and brother to be a part of this,” she says. “But they refused to listen to me.”

Shivani, who had initially been part of the wedding procession, found herself confined to one of three rooms with her mother and the other women, while the men celebrated outside. It was the first time Shivani decided to follow her father and brother to see what all the fuss was about.

“These young girls dancing on the back of the pickup van aren’t performing; they’re being exploited,” she says sharply.

Meanwhile, 600 km away in KushiNagar, Sonali is desperate to escape the orchestra world. Her room in the two-storeyed house where two other dancers live is filled with the trappings of love and hope. The walls are freshly painted blue, there’s a teddy bear on a shelf, and rose petals are scattered across her bed. Though bachelors are not allowed in orchestra houses, Sonali’s relationship with Aakash, a DJ and the son of an orchestra owner, is no secret. The other women dancers have no qualms about her living with him.

Aakash has promised Sonali that they will marry in three months. She has already planned to buy a bright red lehenga, matching jewellery, and glittery shoes. But for Sonali, this marriage holds something more.

“Aakash promised me he would take me out of this world of orchestra,” she says quietly. “We’ll have a simple life in his village house, and he’ll earn for the family.” Aakash nods earnestly, holding her hand. “It’s just a matter of months before she stops dancing,” he assures.

Just then, another customer arrives, and Sonali hurriedly scrambles from her cot to spruce herself up.

(Edited by Prashant/Photos by Praveen Jain)

COMMENTS