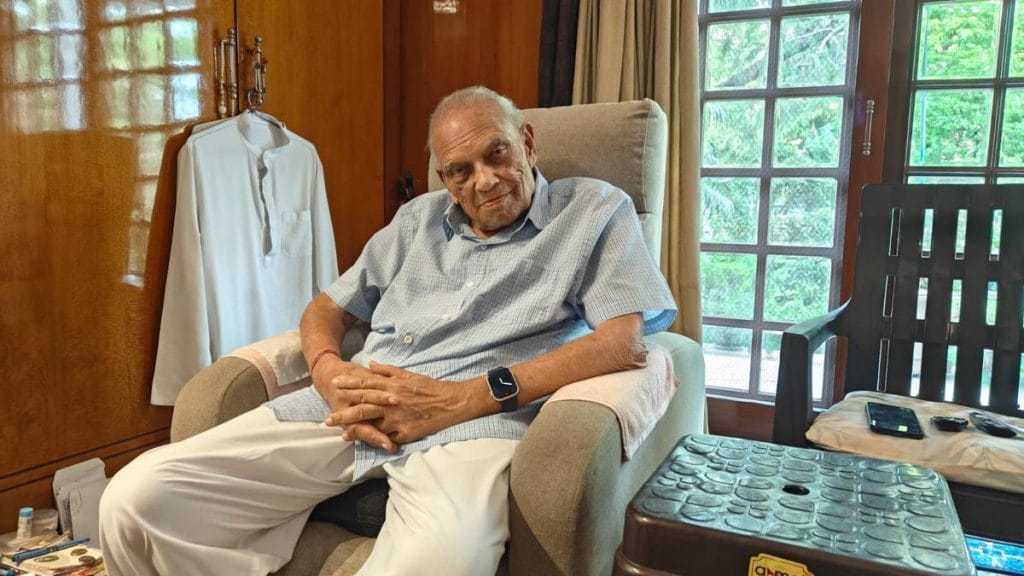

Jaipur: Every week, 92-year-old Kushal Chand Surana arrives in his wheelchair at Rajmandir Cinema to make sure everything is running smoothly. This day is special: the first Hindi-dubbed premiere of Jurassic World Rebirth. In his crisp white kurta-pyjama, the theatre owner smiles as Warner Bros executives greet him at the invite-only event.

“Saying hello to Surana sir is mandatory,” said a distributor, grinning. “We had to have the premiere here after our long, enduring relationship.” For Surana, this is simply the natural order of things.

“In Jaipur, cinema means Rajmandir,” he said.

While many single-screen theatres across India are fading into memory, Rajmandir is thumbing its nose at the odds. It is a unicorn in the age of multiplexes and streaming.

Single-screen halls have dwindled from 25,000 in the 1990s to around 6,000 now, with dirges sung about their future, but the pink landmark still pulls full houses, hosts trailer launches, and now even screens Hollywood premieres.

It’s arguably Bollywood’s favourite single-screen theatre.

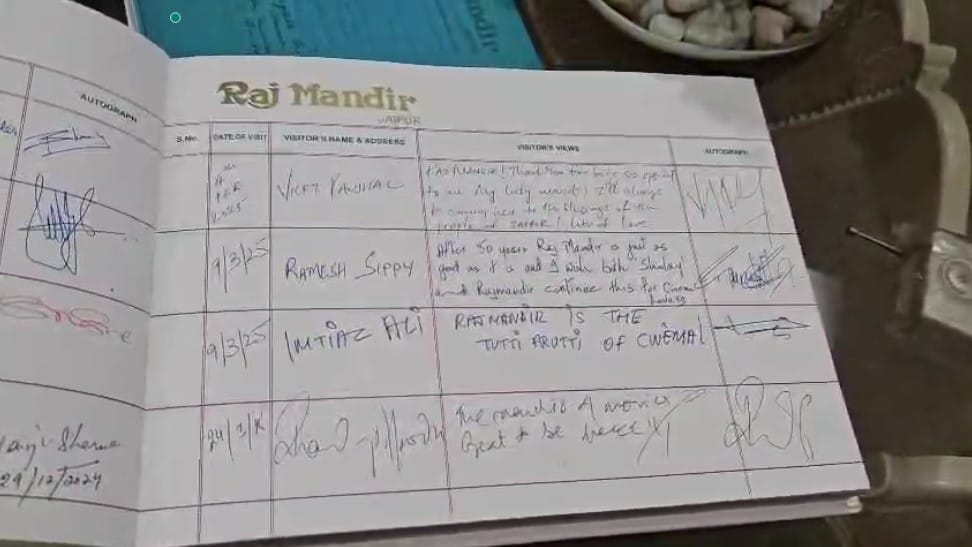

From Raj Kapoor in the 1970s and Amitabh Bachchan in the 80s to contemporary actors like Ranbir Kapoor, Rajmandir has been a magnet for stars for 50 years. In recent months, Rajkummar Rao and Vicky Kaushal have climbed the narrow spiral staircase to wave to cheering fans from the small balcony, posing against posters of their films.

In 2023, the makers of Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3 chose Jaipur over Mumbai for their trailer launch. Lead actor Kartik Aaryan later thanked the hall when he won the IIFA Best Actor award. This year, Ramesh Sippy attended a special screening of Sholay to mark 50 years of the film, which also coincided with Rajmandir’s own golden jubilee. In March, Sunny Deol came to launch the trailer of Jaat, followed by Rajkummar Rao and Wamiqa Gabbi for Bhul Chuk Maaf. Every staff member has a story about the stars who’ve come here.

Raj Kapoor would say, if every theatre maintained itself like Rajmandir, films couldn’t flop — people would keep coming back again and again

-Kushal Chand Surana, owner of Rajmandir Cinema

“Vicky Kaushal came here for the promotion of Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, which was a hit. He calls this place his lucky charm. He came back for Sam Bahadur and then again for Chhava,” said Ankur Khandelwal, who manages the theatre’s daily operations.

The single-screen theatre has succeeded not on nostalgia alone but on reinvention. You can still get snacks like bread pakoda for under Rs 100, but the hall also boasts Dolby Atmos sound. It’s old-world charm meeting the business of spectacle.

This glamour is not new for Surana. He has long rubbed shoulders with the who’s who of the entertainment industry, not only through the theatre but his flourishing jewellery business. The family firm, Bhuramal Rajmal Surana, known for its kundan and meenakari work, has counted Gayatri Devi, Rekha, and Dilip Kumar among its patrons. But Surana’s crown jewel is his beloved Rajmandir.

“I’m not a movie buff but my love is for this legacy I was given, and which will always be a part of this city. We do not do it for money, but for the legacy,” he said, the hint of pride evident in his voice.

And keeping that legacy alive are the moviegoers who still flock to Rajmandir.

Also Read: From Sundance to Venice—2025 marked a breakthrough year for Indian indie films

‘Royal experience’ on a sliding scale

A Wednesday afternoon at Rajmandir plays out like a matinee starring the audience itself. The show begins in the foyer, where tourists and local residents alike have their cellphones out, be it young college-goers making a reel, or a housewife in ghunghat lifting her veil for a quick furtive selfie.

The pink-coloured theatre looks like a delectable dessert against the blue of the Jaipur sky. But the exterior pales in comparison to what lies inside — giant chandeliers, stucco walls, a ceiling filled with stars, and sweeping staircases lit up by the warm glow of lamps. Even the washrooms have a royal theme, marked King and Queen for men and women.

You go to a multiplex, and there’s a gold class where you get special treatment. Here, people from all economic backgrounds sit on the same sofa, enjoying their samosas or pizza. When we talk of cinema, isn’t that what has been missing — the joy of watching with everyone from society

-Kanika Aggarwal, a regular visitor

Some gawk at the trophies placed inside a glass cabinet, others admire a wooden replica of the theatre, and many just revel in sinking into leather sofas separated by pots of flowers and lamps.

“You go to a multiplex, and there’s a gold class where you get special treatment. Here, people from all economic backgrounds sit on the same sofa, enjoying their samosas or pizza. When we talk of cinema, isn’t that what has been missing — the joy of watching with everyone from society?” said Kanika Aggarwal, a regular since she was a child.

There’s a theatricality to the entire experience. Before every screening, white light floods the lobby; at interval, it turns blue as Ustad Bismillah Khan’s shehnai filters into the air. The heavy velvet curtain lifts on a gigantic screen, as viewers take their places in gem-named seating — Ruby, Emerald, Diamond — a nod to the Suranas’ jewellery roots. It’s a luxurious experience for all with a sliding scale, starting from Rs 150 for the front rows and going up to Rs 500 for a premium box.

It’s that “royal feeling” which has brought Payal Kushwaha, her tourist driver husband Sasikant, and their visiting family members from Uttar Pradesh to the theatre.

“We feel welcome here, and even guards treat us with respect. We get the tickets for Rs 150 in Ruby,” said Payal, cradling her three-month-old daughter. The group has come to watch Housefull 5, but it’s also a sightseeing trip.

“Our relatives have come from UP, and if you come to Jaipur, you have to come to Rajmandir and watch a movie,” added Payal with a smile.

As Akshay Kumar makes his onscreen entry with Nargis Fakhri, hoots and wolf-whistles fill the hall. A teenager rushes in with tubs of popcorn as her siblings hiss, “You will miss the film!”

Till interval, the crowd is fully engrossed in the hijinks playing out on the 73×33 foot screen—a rarity in compact multiplex halls where screens are typically 45 to 50 feet wide.

Among the visitors are 23-year-old Gurcharan Singh and his girlfriend, who’ve come from Chandigarh on a “secret getaway”.

“Our autowallah told us about this theatre,” said Singh, as the couple snapped pictures.

Tourists make up a big share of the daily footfall for the four shows timed at noon, 3 pm, 6 pm and 9 pm.

“It is very normal for foreigners and domestic tourists to purchase tickets to get inside and watch a film. Some foreigners just want to experience what it feels like to watch a film in India. They buy popcorn or a coffee and just sit for a few minutes, absorbing the atmosphere,” said Khandelwal. He claimed that Rajmandir earned higher than most multiplexes in the city, flashing some data on his WhatsApp, but refused to discuss specifics.

How it all began

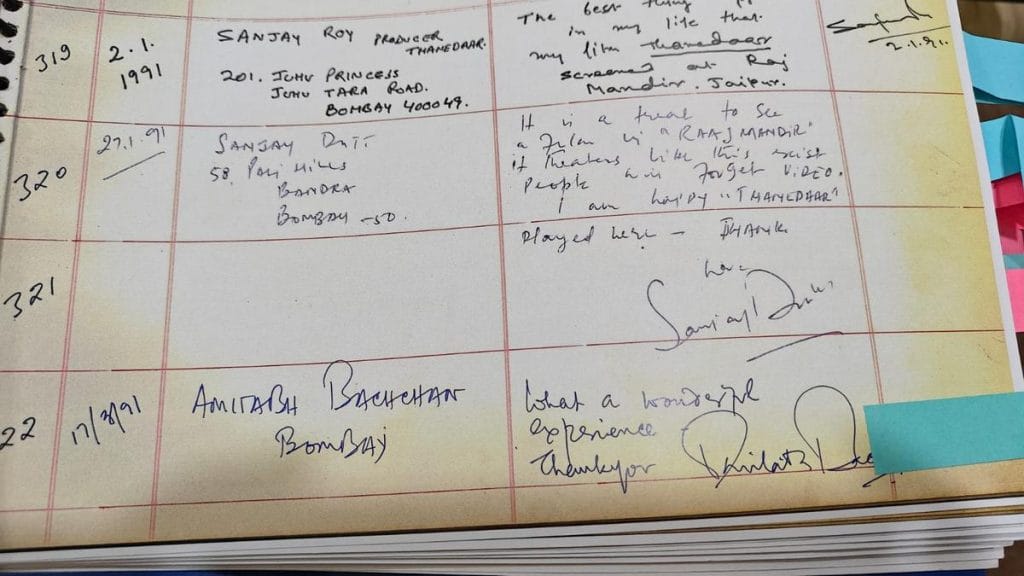

A yellowing visitors’ book reads like a recap of Rajmandir’s history. Hum Aapke Hain Kaun ran for 75 weeks, Ram Teri Ganga Maili for 74. Both directors later left heartfelt notes in its pages.

“I am glad Vivaah had Rajmandir,” scribbled Sooraj Barjatya, recalling the golden run of that film. Kapoor also shared his thoughts on 16 October 1985: “I wish other exhibitors of India learn from Rajmandir how to exhibit a film.” In 2011, his grandson Ranbir Kapoor added: “Feels great to be part of history…”

The theatre’s journey began a decade before it opened on 1 June 1976. It was the brainchild of Surana’s brother-in-law, Mehtab Chandra Golcha.

“He had already built the Minerva theatre in Mumbai and Golcha cinema in Delhi. Once the then [Rajasthan] chief minister Mohanlal Sukhadia asked him, why have you not built anything in Jaipur where you belong. That’s how the planning started,” said Surana.

Minerva, famous for running Sholay for five years, shut in 2006. Golcha closed almost exactly a decade later. Of the three, only Rajmandir was destined for longevity.

In those days, horse-riding sentries used to be sent by the nearby police station to maintain law and order, because on the opening weekend, crowds would spill over to the streets

-Kishore Kumar Kala, accounts manager

The foundation stone was laid in 1966 by Sukhadia, and architect WM Namjoshi — the man behind both Minerva and Golcha — was brought in to design Jaipur’s own Art Moderne landmark.

“It was Golcha’s vision that Namjoshi replicated on paper and in construction,” said Surana.

At first, there were roadblocks. Neighbours objected to the theatre’s proximity to St Xavier’s School and Suraj Hospital. Then there were lawsuits. It almost looked like Jaipur would not get its own art deco hall.

That was when Kushal Chand’s father, Rajmal Surana, stepped in to complete construction and keep it in the family.

Finally, the theatre got off the ground. Then chief minister Hari Dev Joshi inaugurated it. In old black-and-white photographs, he is seen flanked by his security detail, walking beside Surana, who was then in his 40s.

The first film to be screened at the cinema was Charas, starring Dharmendra and Hema Malini.

“In those days, horse-riding sentries used to be sent by the nearby police station to maintain law and order, because on the opening weekend, crowds would spill over to the streets,” said Kishore Kumar Kala, the 83-year-old accounts manager who has worked here right from the beginning.

Early on, Rajmandir owed much of its crowd to a nearby dharamshala run by Gujaratis. The traders staying there would drop in to catch a film, and soon it became a ritual for visiting businessmen to bring their families. From Nagaur to Ajmer, people from towns around Jaipur made it a point to visit Rajmandir.

“Whenever it was a major film, there would be a sea of people. There would be 1,200 inside the theatre, 1,200 in the foyer waiting for the next screening, and 1,200 on the road waiting to enter,” said Kala.

But Rajmandir did not immediately rake in profits.

Housefull for decades

At a time when money was not quite flowing in, well-wishers advised the Suranas not to spend too much on the theatre’s interiors. They did the opposite.

“We got high-quality carpeting done by a local vendor, who made it to order for us. But eventually, it was Jaipur’s people who would actually take care not to spit or smoke inside, looking at the quality of interiors offered,” said Surana.

As the eldest son, he took over from his father, running the hall with the same love and discipline.

Back when most theatres used huge fans for cooling, Surana installed central air-conditioning and a state-of-the-art sound system. The hall once had 1,200 seats, but these were reduced to 800 last year after an upgrade to push-back chairs.

What hasn’t changed is the old-world pomp.

“I used to enjoy watching the reactions of the audience more than watching films. Some would be completely dazzled by the lights or the big screen. People would urge each other not to soil the carpet, because it looked so regal,” Surana said.

Workers arrive at eight each morning to clean and polish every inch of the theatre. By noon, the place is sparkling, ready for guests. The aroma of fresh samosas, kachoris, popcorn, and coffee fills the reception.

Surana has presided over it all for decades, keeping an eye on the hall from his office. Sometimes, his wife and children would join him to catch the latest blockbuster.

I used to enjoy watching the reactions of the audience more than watching films. Some would be completely dazzled by the lights or the big screen. People would urge each other not to soil the carpet, because it looked so regal

-Kushal Chand Surana , Rajmandir Cinema owner

He recounted fond memories of bringing his daughter Dipti to see Umrao Jaan.

“She was very fond of dancing, and in those days, Umrao Jaan was playing in the theatre. She would accompany me, timing her visit to sneak in and watch Rekha ji’s dance in In Aankhon Ki Masti Mein,” said Surana with a chuckle.

The plush carpeted floors have felt the footsteps of celebrities and politicians from far and wide—from former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to Soviet finance minister Victor Dementzev in 1980, to the well-known Pakistani journalist Khalid Husain, from The News, in 2007.

“Absolute pleasure to be here. Lot of childhood memories came alive!” reads an entry by Rajasthan Deputy Chief Minister Diya Kumari in the visitors’ book.

Carefully curated and maintained photo albums show moments frozen in time, such as a young and dashing Raj Babbar addressing a crowd during the promotion of Insaaf Ka Tarazu (1980), and Amitabh Bachchan sitting with Surana over a plate of freshly made samosas.

A major source of pride for Surana is how many distinguished guests have praised Rajmandir for being “so well-maintained”. Raj Kapoor once said it was the reason films did so well there.

“He would say, if every theatre maintained itself like Rajmandir, films couldn’t flop — people would keep coming back again and again,” said Surana.

Kala added that Kapoor was also struck by how well the prints were preserved through countless shows.

“When Raj Kapoor visited the hall, he was impressed with how I had maintained the prints. He declared he would send me a reward once he went back to Mumbai,” said Kala, adding that the actor died before he could do so.

It’s a symbiotic relationship between movies and these old halls. They are where movie fever really thrived in small-town India. Even now, as they groan under outdated infrastructure, high costs, and competition from multiplexes, single-screen theatres haven’t given up the ghost yet. There have been pockets of revival with films like Pathaan, Jawan, Animal, and, more recently, Zubeen Garg’s Roi Roi Binale in Assam.

Last year, the Uttar Pradesh government even announced incentives to help single screens upgrade their facilities. In Maharashtra, a panel was set up to study their challenges, and NCP leader Ajit Pawar led a protest over their plight as well.

For Rajmandir, though, its continued relevance has been organic — the result of forward thinking and a few smart decisions. The family considers it a source of pride but not a money-making machine, so they’ve kept ticket prices relatively low. At the same time, they’ve been proactive about promotional events, which has helped ramp up their visibility over the past five-six years.

Also Read: How big stars and bloated blockbusters are bleeding Bollywood dry

Still running the show

A few kilometres from Rajmandir is Surana Enclave, where a luxurious bungalow houses Kushal Surana, his siblings, and their future generations. Each bungalow sits separately within the same premises, with plaques naming the head of each family.

For the most part, Surana keeps tabs on Rajmandir from his room, surrounded by stacks of files, jars of snacks, trophies, and framed photographs. Two golden retrievers wander in and out, while an entourage of staff members bustles around, tending to everything from the huge lawn to the fleet of cars in the driveway to lunch.

“We mostly have Rajasthani food at home, though I like South Indian food too. When Raj Kapoor came, it was a special Rajasthani lunch,” said Surana.

His grandson and family shuttle between Jaipur and abroad, as he slowly hands over the reins of the family business to the next generation. He says his grandson has shown the greatest interest in continuing the legacy of the cinema hall.

There are signs of the large, tightly knit clan everywhere. One framed photo shows Surana and his four siblings in black bandhgalas and red pagdis at a wedding, another has the women of the family in full Rajasthani finery. There are also wedding pictures of his children, and snapshots of his grandsons. But for Surana, business is still top of mind.

“Surana ji cannot sleep if he does not visit the hall,” said Kishore Kala, who was chief technical officer even before Rajmandir formally opened. “These days it’s just a call, asking if everything is in order.”

Even now, though, Surana makes his way to the theatre on important occasions and for finalising promotion deals.

While many single screens struggle to fill seats, Rajmandir keeps bringing stars and premieres to Jaipur. The hall has upgraded to keep pace with the times without letting go of its history. The theatre now has its own Instagram page to share updates about star visits, promotional events, and other updates.

“We started doing paid promotional events around 2019, and now producers approach us for song or trailer launches, like Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3,” said Ankur Khandelwal, who joined when he was in his 20s in 2014 and now handles everything from maintenance to Surana’s calls. His phone constantly buzzes as he oversees replacing a faulty lock while answering Surana’s general queries about the theatre.

Khandelwal also negotiates with production houses keen to associate with Rajmandir.

“We hosted Jurassic Park’s first Hindi premiere, and I’m in talks a production house down South for their trailer release here,” he said. The invite-only event would be another milestone for the theatre, which broke into the concept of non-Mumbai trailer launches with Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3, following it up with others such as Jaat.

Before the release of Jurassic Park, Warner Brothers issued a statement: “By choosing the revered halls of Rajmandir, the crown jewel of single-screen cinemas, and synonymous with legendary Hindi film screenings, we aim to honour this heritage and truly connect with our passionate fans of the Hindi dubbed version.”

Surana, meanwhile, is less taken with the new era of cinema.

“I do not watch movies now. There’s no plot or music,” he said, waiting for the PR and events team to arrive for a meeting on the premiere. “What I want is for people to walk in, enjoy a good movie, and feel like this hall opened yesterday.”

This is the first article in a three-part series on single-screen theatres in India. Read the other articles here.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)