Jind: Nirmala stood in silence, tears slipping down her face. Beside her were her son Himanshu and her husband, both quiet, both trying to stay strong. The family had travelled from Haryana’s Narnaul to Jind, clinging to one last hope: that the Aggarwal Sammelan would finally bring a bride for Himanshu.

In her hand, 50-year-old Nirmala held a worn booklet — pages filled with names, faces, and biodatas. But once again, they were returning home, just the three of them, hearts heavy and still no bride.

“We have everything,” Nirmala said, struggling to hold back sobs. “His father earns Rs 20,000 a month. My son makes Rs 40,000. We live a comfortable life. Still, I don’t know why no one wants to marry him. He is 30 already. We’re exhausted. Coming here was our final hope.”

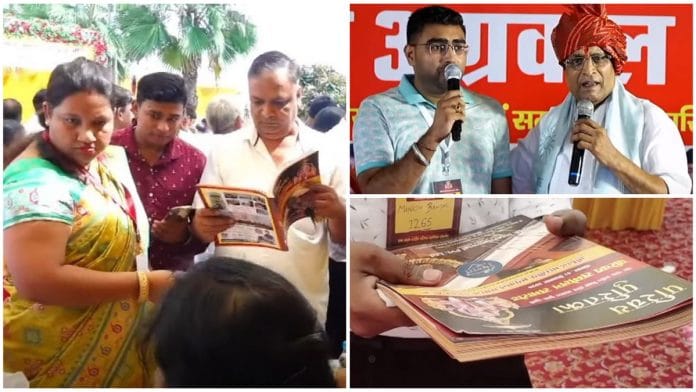

Nirmala is not alone in this pain. Hundreds of families — mothers, fathers, hopeful sons and daughters — gathered at Shri Shyam Garden in Jind on 7 September for the North India-level Parichay Sammelan (Introduction Gathering), organised by the All India Aggarwal Samaj, Haryana. From 10 am to 5 pm, all the participants scanned the crowd with a common dream: the perfect bahu, damaad, or spouse.

More than 1,500 eligible candidates arrived from 17 states, and even from abroad, all in search of ‘the one’.

The event, usually held once in five years, is spearheaded by Raj Kumar Goyal, president of the Akhil Bhartiya Aggarwal Samaj-Haryana. Cabinet ministers Vijay Goel (Haryana) and Barinder Goel (Punjab) attended as chief guests, along with Pradeep Mittal, national chairman of the Akhil Bhartiya Agrawal Sangathan.

In a country where dating apps are slowly replacing family networks, one community is making sure matches are made with the traditional metrics but with a modern twist.

The Aggarwals, one of India’s most prosperous and influential communities, have long been the epitome of success in business, trade, and industry. With an estimated population of 5.6 million, they’ve built an empire of enterprise. According to the Hurun India Rich List 2025, the Aggarwal and Gupta surnames reign supreme with 12 entries each among the country’s most valuable family-run businesses.

But if business is their stronghold, the marriage market is turning into a weak spot. There’s a rising tide of delayed marriages. Wealth, education, and modern outlooks haven’t made finding matches any easier.

And so, from banquet lawns to biodata booklets to glowing stage introductions, the community is trying to reinvent matchmaking, one sammelan at a time. Behind it is a growing movement, led by Raj Kumar Goyal and Pradeep Mittal, that seeks not just to join Aggarwals in matrimony but to rekindle the art of arranged marriage across India.

These meetings are the only reliable way left to encourage timely marriages. It’s how we fight social isolation. Rising crime. How we protect our cultural fabric

-Raj Kumar Goyal, president of the Akhil Bhartiya Aggarwal Samaj-Haryana

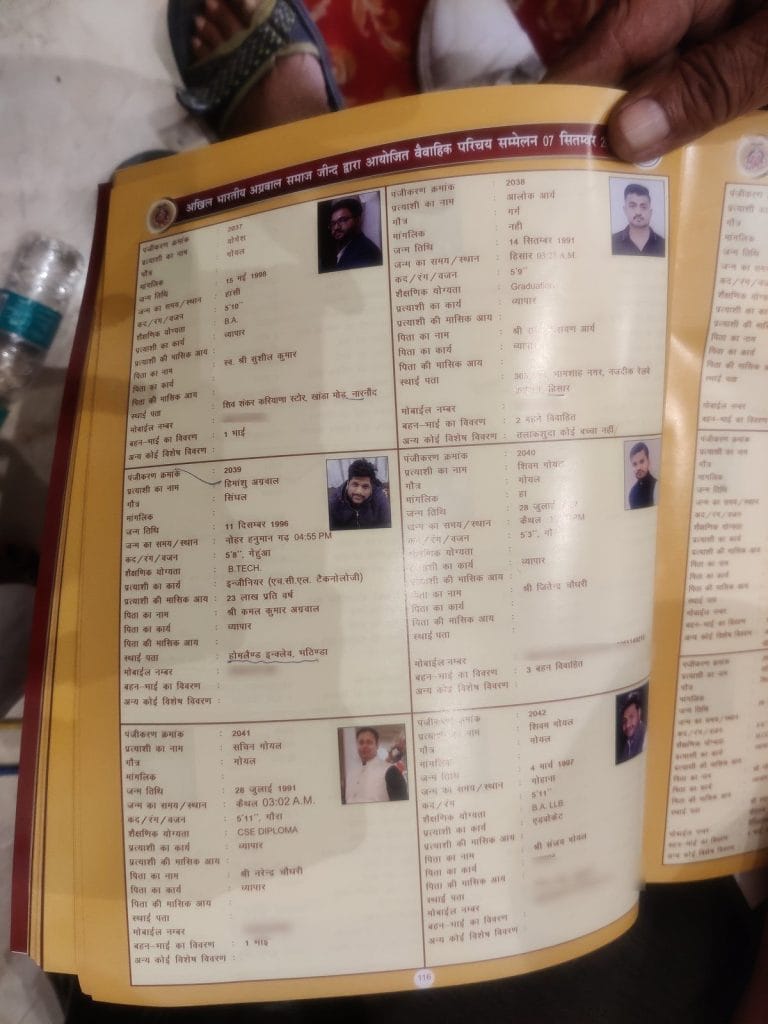

Despite the scale, the Parichay Sammelan operates on a simple philosophy: ‘self-service marriage hunting.’ For a registration fee of Rs 500, each candidate receives a booklet with details of potential matches. If two families like what they see, they are free to take it forward. There are no middlemen. Instead, the ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ are encouraged to sit down for a chat over chai or poori-halwa from the buffet. Women arrive in saris or suits, men in tees or kurtas. Heavy jewellery and shaadi-style finery are rare.

“This hybridity is what’s important about these Aggarwal sammelans. They appear both modern and traditional, as patriarchal as possible, but within that structure, they allow for individual choice and change. When we talk about change in India, it’s important to view it as a movement between tradition and modernity, creating a mix,” said Shiv Visvanathan, professor at OP Jindal University in Sonipat, Haryana.

He pointed out that the sammelans are gaining ground because they offer at least a semblance of choice, in contrast to the old system where the family’s seniormost patriarch would choose a match without question.

“Occupations are evolving, migration is increasing, and families are becoming more fragmented. The notion of ‘my grandparents approved of this marriage’ no longer holds weight, especially in today’s world of high mobility,” he added.

Also Read: Rationalists look for love in new India. Kerala’s Secular Matrimony swipes left on religion

The ‘dharma’ of rishtas

Families moved through the crowd with purpose — some exchanging numbers, others swapping hopeful glances and hushed whispers.

“Did you find anyone promising? Any talks happening?”

On stage, one by one, candidates introduced themselves, each sharing their version of an ideal partner.

“I’m looking for someone sanskaari,” declared a young man. “Whether she works or not doesn’t matter, but she must have high values.”

Next to him stood Priya Bansal, 25, a private school teacher from Hisar. With a polite smile, she shared her own expectations: “No smoking, no drinking, and he should be financially independent. That’s all I’m looking for.”

In the crowd, quiet murmurs had already begun. “That boy and this girl are actually not a bad match.” Or, “They’d make a good pair.”

Bansal hadn’t volunteered to be here. She was brought by her family, nudged onto the stage by her mother and brother, who now stood beside her, offering praise and reassurance. “You did well. You spoke beautifully.”

She played along, comfortable with the balance of agency and tradition here.

“I think all girls should come forward like this and openly share what they want in a life partner,” she said. Though she said she loved her teaching job, she made it clear that if the family she marries into didn’t want her to continue, she’d leave it without question.

“I’ll happily do whatever my husband and his family want,” she added.

We’ll go home, shortlist more, and then start reaching out. Do I believe everything written here? No. That’s why we say — you must decide for yourself, verify for yourself. But at least within our community, there’s some understanding. Some trust

-Manish Bansal, would-be groom

Meanwhile, candidates like Manish Bansal, 30, a manager at an insurance company in Chandigarh, were more seasoned. “This isn’t my first time looking,” he said with a smile. “But these events make it feel more real. More possible.”

For Manish, the Aggarwal sammelan was a practical solution to the complexities of modern matchmaking. It brought together people who were genuinely serious about marriage, offering a space where conversations could happen openly, doubts clarified, and connections formed. And he’s keen to find love within the confines of his community.

He had registered a month in advance and has been poring over his booklet of potential matches.

“We’ll go home, shortlist more, and then start reaching out. Do I believe everything written here? No. That’s why we say — you must decide for yourself, verify for yourself. But at least within our community, there’s some understanding. Some trust,” he said, flipping the booklet open and pointing at the numbers he’d already saved.

Around him, families hovered near their sons and daughters, casting a keen eye around the gathering. Some handed out printed biodatas, others exchanged numbers.

This anxiety around marriage — especially when it doesn’t happen soon enough — is echoed in homes across the country.

In Gurugram, hope springs eternal for Shanti Gupta, who lives in a new flat with her two sons. One is already married, but for love. The other, Dheeraj, has flatly refused to marry “just because it’s time”. She still dreams of giving her future daughter-in-law sarees, cooking her favourite meals, planning family gatherings.

But finding a good Bania girl is not high on Dheeraj’s list of priorities.

“I want to marry for love,” he said. “Yes, I’m settled. I’m an architect. I earn well. But that doesn’t mean I should marry just because my mother thinks I’m getting too old. That’s my decision.”

Shanti Gupta’s desire for the perfect bahu recently escalated into a conflict between mother and son.

“I’ll marry after you die,” Dheeraj had snapped in frustration.

Still, her hopes haven’t dimmed. “If he wants to marry outside the caste, that’s fine,” she sighed. “I just want to see him settled.”

But Dheeraj is firm. He’s not afraid of love or commitment, but of responsibility.

“Before I enter into a relationship, I want to be sure I can truly emotionally support someone else. That I’m ready to make promises I can keep.”

For Goyal, one of the sammelan organisers, these stories are far too common — and deeply troubling. Parents, he said, now have endless aspirations. First, they want their son to get a job. Then become an engineer. Then clear IAS. By the time he’s done, he’s too old to get married. The matchmaking events are a necessary foil to these modern dilemmas, according to him.

“These meetings are the only reliable way left to encourage timely marriages,” he said. “It’s how we fight social isolation. Rising crime. How we protect our cultural fabric.”

Every successful match is a spiritual act, as far as he is concerned. “Getting one marriage done is a work of dharma. And here, we help create hundreds.”

A mission to marry

In a country where marriages post the age of 30 are becoming an “alarming” trend, Goyal is trying to revive the lost traditions of matchmaking in a modern, dignified, and scalable way.

For over two decades, he has organised “Parichay Sammelans” — large-scale events that bring together eligible men and women (and their families) under one roof. These are platforms of possibility, designed to spark connections in a world where personal networks have withered and traditional matchmakers are not nearly as ubiquitous as they once were.

“Our sons and daughters are reaching the age of 30-35 without getting married. Parents are anxious. Earlier, marriages were arranged by elders or middlemen. Today, there’s no one left to help,” said Goyal.

It all started in 2001, when Goyal and his team visited Indore and saw a community matchmaking initiative in action. Inspired, they asked themselves: why not bring something similar back to their own region, where the shortage of suitable matches was becoming a silent epidemic?

The first event, however, was met with scepticism.

“People said we were insulting boys and girls by calling them on stage. They called it undignified. But we knew that if we didn’t act now, the social fabric would break,” he said.

Goyal barrelled forward and Parichay Sammelan is now something of a movement, with hundreds of marriages to its credit. Today, he and over 450 volunteers across Haryana and neighbouring states organise these events every 2-3 years at the district level. Once every five years, a grand North India Sammelan is held.

Before, our daughters were served up like dolls — on plates. The groom’s family would come, look at them in temples, hotels, or dharamshalas, and leave with vague promises. It was humiliating. I wanted to end that

-Pradeep Mittal, national chair of the Akhil Bhartiya Agrawal Sangathan

Instead of whispered negotiations in drawing rooms, these sammelans put everything out in the open. Everyone gets a booklet, candidates go up on stage and introduce themselves, and parents in the audience jot down names for later calls.

“It’s dignified, structured, and transparent,” said Goyal. “The families take those booklets home. In the next 10-20 days, they follow up with matches they’ve marked. That’s when real conversations begin.”

He insists there have been numerous success stories, recounting a recent event in Karnal where a girl who’d not received a single proposal in years ended up with 200-300.

For all their reach, though, the sammelans don’t always cut across class. Some matchmakers say the rich prefer to keep matters more exclusive.

“Wealthy and upper-class individuals still come to us, but their requirements are usually that the person should come from a good family. Business families prefer to marry within their own circles. If the financial status matches, the marriage goes ahead. Both parents and children usually agree on this,” said Vikas Gupta, a matchmaker who has been running his own Aggarwal marriage bureau for the past 25 years.

A proposal to the PM

Meeting-and-greeting events are just the beginning for Goyal. He is lobbying the government to step in and recognise matchmaking and timely marriage as a national concern.

“We’ve sent proposals to the government, to the Prime Minister. We want every state to start collecting marriage data and hold official matchmaking events. Only then will parents realise how serious this issue has become.”

He draws a direct line between marriage delays and rising crime rates, arguing that loneliness and frustration, especially among unmarried men over 45, are contributing to social unrest.

“If marriages happen on time, crime will reduce. It’s that simple.”

This hybridity is what’s important about these Aggarwal sammelans. They appear both modern and traditional, as patriarchal as possible, but within that structure, they allow for individual choice and change

-Shiv Visvanathan, professor at OP Jindal University

Another radical proposal from his team is the abolition of surname changes for women after marriage. Echoing what has long been a feminist concern, he said women should not have to deal with administrative and legal problems brought about by a name change, including if they want to remarry later.

“A girl lives with her name and identity for 25-30 years. Then overnight, her surname, her father’s name — everything is changed. Why should that be mandatory?” said Goyal. “We want this to become a national campaign. Marriage should not mean the erasure of identity.”

‘Dolls on plates’ to ‘no thank you’

While Goyal has taken the baton forward, credit for India’s first Parichay Sammelan goes to Pradeep Mittal, national chair of the Akhil Bhartiya Agrawal Sangathan. A stalwart of the community organisation for over five decades, Mittal was the mind behind turning matchmaking into a public event.

“It began in 1978. Before that, our daughters were served up like dolls — on plates. The groom’s family would come, look at them in temples, hotels, or dharamshalas, and leave with vague promises. It was humiliating. I wanted to end that.”

Mittal introduced voluntary on-stage introductions and biodata cards, allowing families to make informed, respectful choices — a stark departure from the objectifying practices of the past.

“We don’t want a crowd. We want the boy, the girl, and their emotions. If someone likes a profile, they mark it. Then they go home, verify it, and proceed.”

Mittal has taken this format to cities across India, even organising events internationally. Over time, he has witnessed dramatic changes in gender participation. Women aren’t quite as keen as they used to be.

“In the 70s and 80s, 80 per cent of participants were girls. By 2000, it was 50-50. Today, 80-85 per cent are boys. Only 15-20 per cent of those who register are girls,” he said.

He chalked this up to women making strides as social, educational, and career spaces open up, while men remain stuck in the status quo. Girls today seek partners who are more qualified or earn higher salaries than them. This creates a gap in communities where boys haven’t caught up with modern career aspirations.

“Now, girls are more educated. They pursue higher degrees, good jobs, and delay marriage. But boys? Many are still stuck in family shops, basic businesses. There’s a mismatch of ambition and expectation,” Mittal said.

Also Read: Indian weddings get a new destination in tier-2 cities—Rishikesh, Khajuraho, Corbett

A race against time—and pre-wedding shoots

For all his forward-thinking views, Mittal contends that 25 is the ideal cut-off for marriage. Anything beyond, he says, risks trouble. No less than a social and medical emergency unfolding in slow motion.

“We recently passed two key proposals: first, boys and girls should ideally marry by age 25. Doctors say marrying at 30-35-40 impacts fertility and emotional bonding.”

And then there’s a new trend he finds deeply troubling: pre-wedding shoots.

“These shoots are dangerous. The couple goes away for a week, lives together, gets emotionally involved. Then they return, tell everything to their families — and the relationship breaks before marriage. I’ve seen hundreds of such cases,” he said.

In response, Mittal has pushed a national proposal to ban pre-wedding shoots, arguing that such practices undermine the trust and the sanctity of marriage. As he put it, the more casual relationships become, the more fragile they get.

This is the first article in Baniya Basics, a three-part series on the changing face of India’s mercantile community.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Such an over exaggerated, unnecessary article which doesn’t give any message.

This is dumb as hell ?. They need to accept reality and get with the times.

once they used to hate girl child. It is the consequence of that. Ratio is imbalanced. Early marriage @ 20, 21 is another reason. If there is lack of higher education, only business and business, so there will be a scarcity of competent guys…..

Don’t the upper caste blame reservation or college forum to keep caste intact? Not matrimonial ads or caste based marriage

This is happening in every community others don’t have courage to came out.

There are many South Indian upper castes, where girls are more than boys. Try them

They don’t go with North Indians. Now a days they’re only going after foreigners when going for foreign education.