Teesta Bazar/Jalpaiguri/Gangtok: The Teesta once carried both anger and calm — a river of love that Sikkim’s people sang about in folklore passed down through generations. The songs are still sung, but the river has become a symbol of flood and fury, devouring homes and lives in its path.

This monsoon, the primary water lifeline of eastern India flooded once again, wreaking havoc across parts of Sikkim and West Bengal.

“I have rebuilt my house thrice in the last three years. We don’t even know if there’s any point anymore,” said 38-year-old Dinesh Lama, now living in a community centre in West Bengal’s Teesta Bazar along with dozens of other displaced families.

In the upper reaches of the Sikkim Himalayas—where the Teesta originates—relentless rain battered the slopes this monsoon. Then, in late October, Cyclone Montha in the Bay of Bengal worsened the floods further.

Many constructions along the riverbanks were washed away overnight, displacing thousands. But the feeling among residents wasn’t of shock or surprise; it was déjà vu — a chilling reminder of the 2023 Glacial Lake Outburst Floods.

The problems plaguing the Teesta remain the same: rapidly melting glaciers, new hydropower projects, mismanagement of existing ones, and rampant encroachment along the river’s banks. In short, while climate change is making the Teesta a well-fed, ferocious river as soon as it leaves the mountains, human interference downstream is only making it angrier and more unpredictable.

“Teesta flooding is a man-made disaster,” said Vimal Khawas, professor at the Special Centre for the Study of North East India, Jawaharlal Nehru University. “Unprecedented warming in the mountains is accelerating geomorphic processes — melting glaciers, rise of potentially dangerous glacial lakes — all of which ultimately feed into the Teesta.”

Also read: Sikkim’s war on GLOF. Monks, shamans, scientists are all in the fight

Angry love and shared water

As the lush green mountains of Sikkim turn snowy white, the Teesta springs to life.

Yet the story of this river’s evolution is as volatile as its flow today.

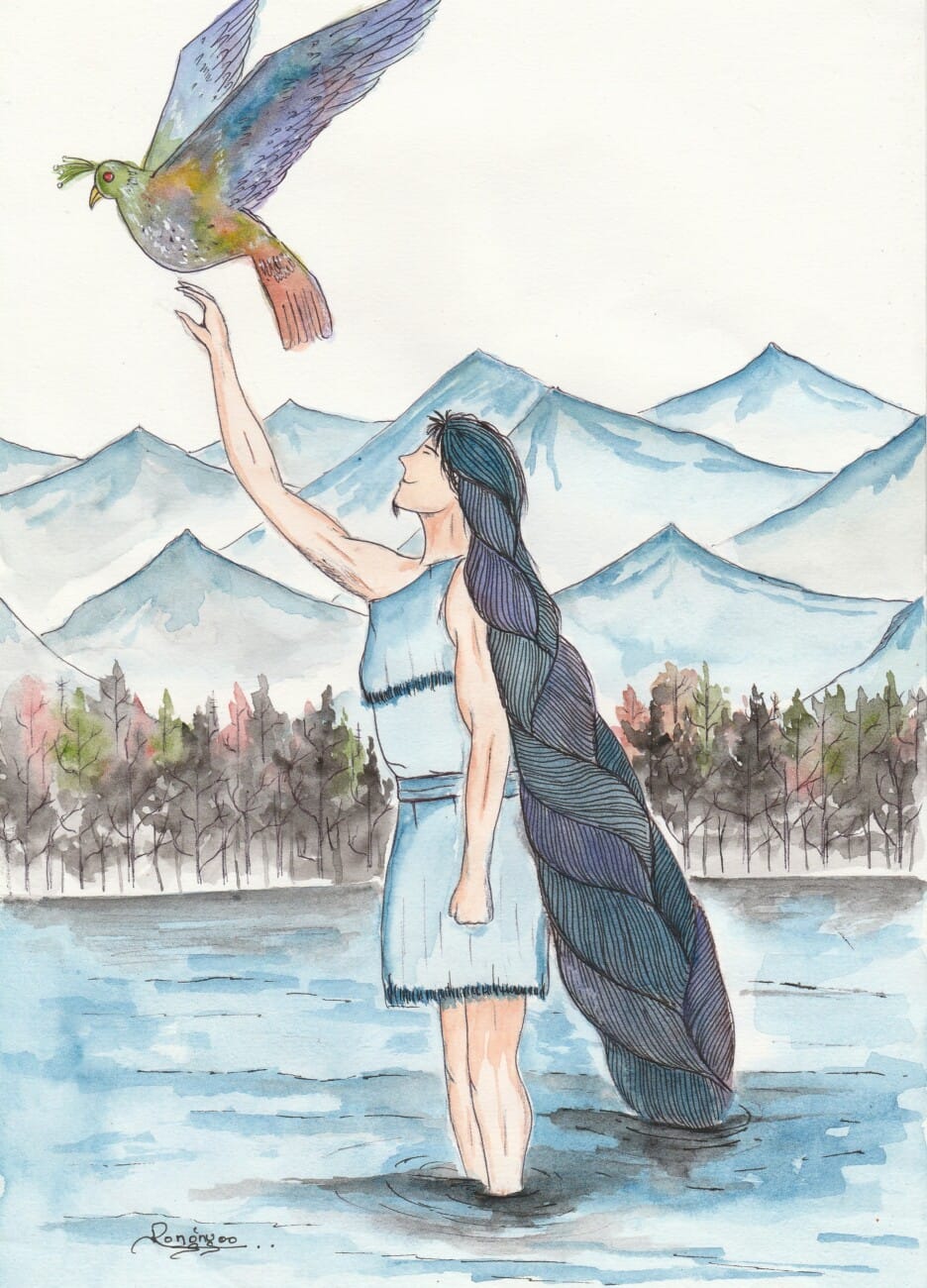

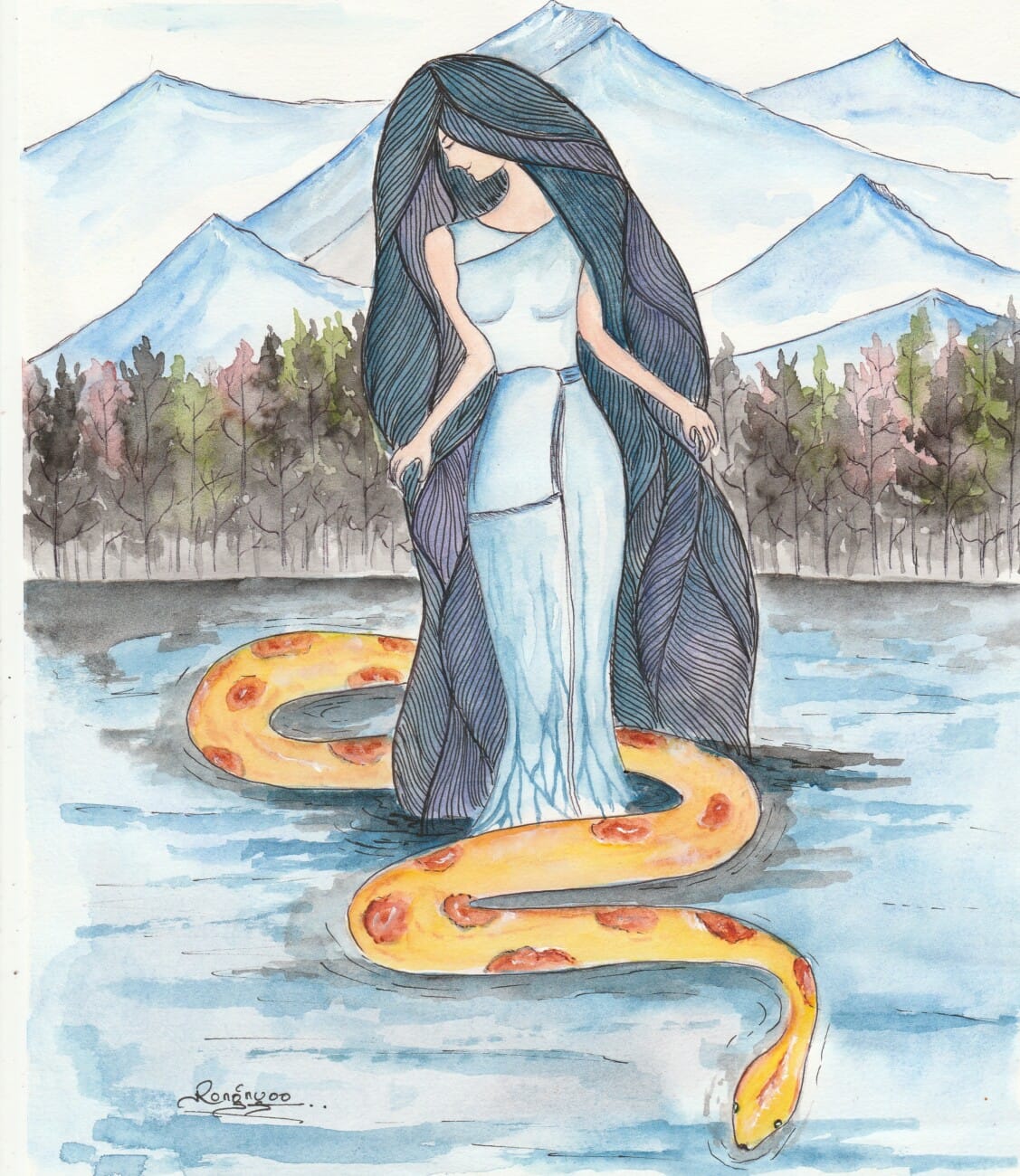

According to Sikkim’s Lepcha community — the Mutanchi Rongkup Rumkup, or “beloved children of Mother Nature and God” — the Teesta was born out of an angry love between two water spirits: Rangeet (now a tributary) and Rongnue (the Teesta herself).

When the gods learned of their love, they decreed that Rangeet and Rongnue would flow together into the plains. To guide them, Kanchen-Chu—the local name for Mt Kangchenjunga—assigned a companion for each: a bird for Rangeet, a serpent for Rongnue.

The bird chose a longer route, while the serpent led Rongnue through shortcuts, bringing her to the meeting point well ahead of Rangeet.

As she waited, Rongnue transformed into the mighty river she is today. When Rangeet finally arrived and found her waiting, he exclaimed, “Thistha”.

Angered that Rongnue had been made to wait, he turned back toward the mountains, unleashing torrential floods in his wake.

This tale of love and competition is still sung in Lepcha wedding songs.

Another version says that Teesta earned its name from the Sanskrit word ‘Tri-srota’, meaning “river of three streams”. It is said that the ancient rivers Karotoya, Atreyi and Punarbhava once joined to form what we now know as Teesta.

The origin story may vary, but all accounts agree that the river was always generous — an abundant and dependable source for Sikkim, West Bengal, and the plains of Bangladesh.

The Teesta flows for about 414 km —spending its first 151 km in Sikkim, another 142 km in West Bengal, and the remaining 121 km through Bangladesh before meeting the Brahmaputra.

But this abundance has also created a conflict. For decades, the Teesta has been at the centre of a tug-of-war between India and Bangladesh. Dhaka has been insisting on inking a water-sharing treaty, but New Delhi remains hesitant.

Last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said a technical team from India would visit Bangladesh “soon” to discuss the “conservation and management” of the Teesta, without mentioning water-sharing. While the Centre has since been non-committal, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has been more vocal in her opposition, arguing that any agreement would impact lakhs of people in north Bengal. In 2017, she offered to share the waters of Torsa, Sankosh, Manshai and Dhansai — but not Teesta.

“Over one lakh hectares of land across five districts are severely impacted by upstream withdrawals of the Teesta’s waters in India and face acute shortages during the dry season,” read a 2016 report by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF). In the initial phase of negotiation, Bangladesh demanded 50 per cent of Teesta’s annual flow between December and May, while India claimed 55 per cent.

The Indian government estimates that about 2,750 sq km of Teesta’s floodplain lies in Bangladesh. The river’s catchment supports around 8.5 per cent of the country’s population and accounts for about 14 per cent of its crop production.

Experts say these numbers show how many lives depend on Teesta. But they also underline the river’s power over the region — a reminder that if her abundance is exploited, she will not be afraid to lash out. It has done so in the past, and there are clear indications it will do so again.

“Locals believe that if Teesta is displeased, the life-giving benevolence of the water could turn into something dark and malevolent, like it did nearly 50 years ago when massive floods in 1968 in Bengal’s Jalpaiguri district killed many who lived along the banks,” wrote author Maya Mirchandani in the ORF report.

“The river turned into a drain of thick silt, and crops and livestock perished. The memory of that flood is now deeply embedded in local village lore.”

Also read: What turned Teesta into a killer? Here’s proof Sikkim flash floods are a man-made disaster

Receding glaciers, swelling Teesta

Tenzin Lepcha, a resident of Sikkim’s capital city, Gangtok, knows that something “ominous” is happening in the Himalayas.

He sees the 2023 GLOF and the 2025 floods as warnings — if humans don’t “mend their ways”, he says, the repercussions will be catastrophic.

“There was a way of life that the original residents here used to swear by. Nature is a provider, but if you begin to exploit it, it will come back to bite you in ways you cannot imagine. That is what is happening now,” Lepcha said.

His instinct is backed by science.

Since the GLOF hit Sikkim and West Bengal, multiple studies have confirmed significant glacier retreat in this region. The research has also pointed to extreme temperature recordings in high-altitude areas — another reason behind the increased flow of water into the Teesta.

A 2023 study by scientists from Madhya Pradesh’s Dr Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya examined 24 glaciers in Sikkim between 1988 and 2018. Half of them had retreated at varying degrees, with at least seven—East Langpo, Lonak, South Lonak, East Rathong, Rula, Tista and Tasha-1—showing consistent retreat throughout the study period.

The Changsang and South Lonak glaciers showed the maximum retreat: 1917.1-170.8 metres and 1328.8-118.4 metres, respectively

Another study published in 2024 by scientists from India’s Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR) and the US’s Byrd Polar and Climate Research Centre highlighted the increasing risk of climate change-induced GLOF in the eastern Himalayas.

“The loss of glacier ice and associated formation and expansion of glacial lakes is unequivocal. The increasing number and extent of glacial lakes threaten downstream communities and infrastructure,” the study warned.

Officials from the Sikkim State Disaster Management Authority (SSDMA) agree. The unprecedented warming of the mountains, they say, is one of the key reasons behind the ferocious flow of the Teesta in recent years.

The India Meteorological Department (IMD)’s archival data bears this out. Between 1980 and 2020, average temperatures in the Sikkim Himalayas rose noticeably — by 1.05 degrees Celsius in Tadong, and 1.98 degrees Celsius in Gangtok.

“When our teams went to rescue villagers after the 2023 GLOF, many mentioned that hours before the disaster hit, the daytime temperature recorded in the nearest automated weather station in the Himalayas was around 2-3 degrees Celsius,” a senior SSDMA official told ThePrint on condition of anonymity.

Anything above sub-zero at such altitudes, the official said, is already a warning bell.

Also read: A trail of debris, loss, feeble prayers—Scenes from Dharali, a village half buried under rubble

Mismanagement of hydropower projects

The recent floods along the Teesta have been in the making for over two decades.

Scientific papers and environmental experts have long warned of the impact of excessive encroachment on the river’s banks. But environmentalists and activists have also blamed the string of hydropower projects approved along the river.

Sikkim has 11 operational hydropower projects. The main Teesta channel has two primary ones—the 1,200 MW Teesta Stage-III and the 510 MW Teesta Stage-V. At least five other projects are currently in the planning or commissioning stage.

Approved in 2005 with an initial budget of about Rs 5,700 crore — which eventually ballooned to Rs 14,000 crore — the Teesta-III project was undertaken by the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) and made operational by 2017.

Tribal communities in Sikkim opposed the dam from the start, citing ecological concerns and the agency’s disregard for local land rights.

Their fears came true in October 2023. As flood waters from the mountains came gushing down, they were held back by the Teesta-III dam in Chungthang. When the dam breached, the water flooded downstream with even more force—carrying debris and destruction in its wake.

“When the water flooded down with debris from the dam, it created more damage. The boulders hit houses and buildings. If it were just water, the damage might not have been this much,” said Rakesh Ranjan, head of the geology department at Sikkim University.

Residents are now fighting to prevent a repeat of the 2023 disaster. They are up in arms against authorities insisting on rebuilding the damaged dams and constructing new ones.

Many protests led by the Sikkim-based people’s movement, Affected Citizens of Teesta (ACT), stress the need for detailed ecological studies before such projects, especially those planned in vulnerable zones.

“This region is extremely fragile. Every monsoon season, we are observing more and more landslides. Any wrong move can be catastrophic for us,” said Sangdup Lepcha, president of ACT.

Currently, he said, only a 10-km stretch between Namprikdang and Dikchu remains free of dams along the Teesta in Sikkim.

But environmentalists also stress the role of ordinary people. Houses, shops and hotels built right on the edge of the Teesta only worsen the aftermath of disasters.

The districts worst impacted by the Teesta’s fury have all been victims of large-scale encroachment. They paid the price — losing families, homes, livelihoods.

“Elders here always said that rivers have memories. It will tolerate things for years, but she remembers who wronged her. In due time, she will always hit back—claim what is hers and destroy everything that makes her shrink,” said Sangdup Lepcha.

Back in West Bengal’s Teesta Bazar, residents say their only escape from these annual floods is to leave town, or at least move their children elsewhere. Many are fed up with the annual ritual of packing up and abandoning their homes during the monsoon, when the Teesta flows to kill.

“It is easy to call our homes ‘encroachments’. We have lived on the banks of the Teesta for decades now. We cannot pack up our entire life and leave overnight. But after everything that we have experienced over the last few years, I think it would be best to leave,” Lama said.

This is the third story in the three-part series Angry Rivers. Read the first on Beas River here and the second on Chenab here.

(Edited by Prashant)