New Delhi: As Vidushi Shovana Narayan dances, her feet massage the floor with rhythmic grace. Her hands teach the intricate mudras of Kathak to MBA students sitting in an intimate circle at Gaziabad’s Jaipuria School of Business. Between class deadlines and stressful exams, they are getting an important mental health break—with a SPIC MACAY live performance of Kathak.

Narayan pauses and invites them to be a part of her bliss. She gestures toward the sky, enacting rain, then shifts her expressions fluidly, transforming into different animals, playfully asking the students to guess which one she just embodied.

When the performance ends, the students flock to her, eager to know the secret behind her boundless energy. The dancer smiles despite the sweat smudging her makeup, radiating quiet joy.

After more than 3 lakh live concerts, India’s 47-year-old premier performing arts institution SPIC MACAY (Society for the Promotion of Indian Classical Music And Culture Amongst Youth) is changing. It began at a time when classical music and dance were relegated to big concerts, Doordarshan, and National Award functions. And teenagers were defining cool as anything Western. Grammy Awards line-up was being shown on Indian television—making Michael Jackson and Madonna familiar names in urban middle class homes. Through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, SPIC MACAY tried to arrest the tide and the slide by dedicating itself to popularising and making accessible classical performances for school and college students.

Today, in a harried, doomscrolling world, SPIC MACAY has updated its core mission for a new age—classical arts to fix anxiety, paranoia, and stress.

As she moves, Narayan recalls a time when in Bihar, baithaks—intimate gatherings of music and dance—stretched from morning till night, filling street corners with spellbinding performances. The paanwalas and rickshawalas would join in to critique the ragas, debating which tune was off and which song should have been sung over another.

Narayan’s audience now ranges from business, engineering, and medical students to young children in rural regions of India. They may not understand the intricacies of Kathak, but her work is much harder today—to get them to just stop looking at their phones. As she enacts Draupadi Haran, the hall falls into stunned silence—proof that classical arts, even in fleeting moments, still hold the power to captivate.

“It is no longer about preaching to the converted; it is about igniting curiosity in young minds, about bringing the intangible depth of our traditions to those who may have never encountered them before,” said Narayan, who was awarded the Padma Shri in 1992 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Dance in 2001.

She recalls a time in Bihar when cultural news ruled the headlines, not politics. It was an era where every classical performance was documented with the same fervour as the film industry is today. The audiences weren’t just passive spectators either, they lived and breathed classical music. But that world has faded.

Founded in 1977 by professor Kiran Seth, this non-political, nationwide, volunteer-driven movement now seeks to demonstrate how it cultivates essential life skills like concentration, patience, and creativity. It is offering solace to an anxious generation, grappling with the fast pace of modern life.

“Everything has been reduced to getting a degree and landing a job, and that’s it. The pressure has stripped learning of its true purpose,” said Seth, recalling a conversation with the Dean of Students’ Welfare at IIT Roorkee. “In a class of 200, barely 10 to 15 attend lectures, while many stay isolated in their rooms for a week. From this isolation, we see suicides and depression—it’s all connected.”

In the 1970s, a Dhrupad recital in New York inspired Seth to organise concerts at Columbia University. Upon returning to India, he was dismayed by his students’ unfamiliarity with classical music and started a small initiative at IIT Delhi. In the early days, funding was scarce and volunteers were few—just two in the first year, a number that later expanded to six dedicated supporters.

Classical arts teach concentration, patience, and creativity. They can take you to an alpha zone which cannot be easily described. It can ease your ‘monkey mind’.

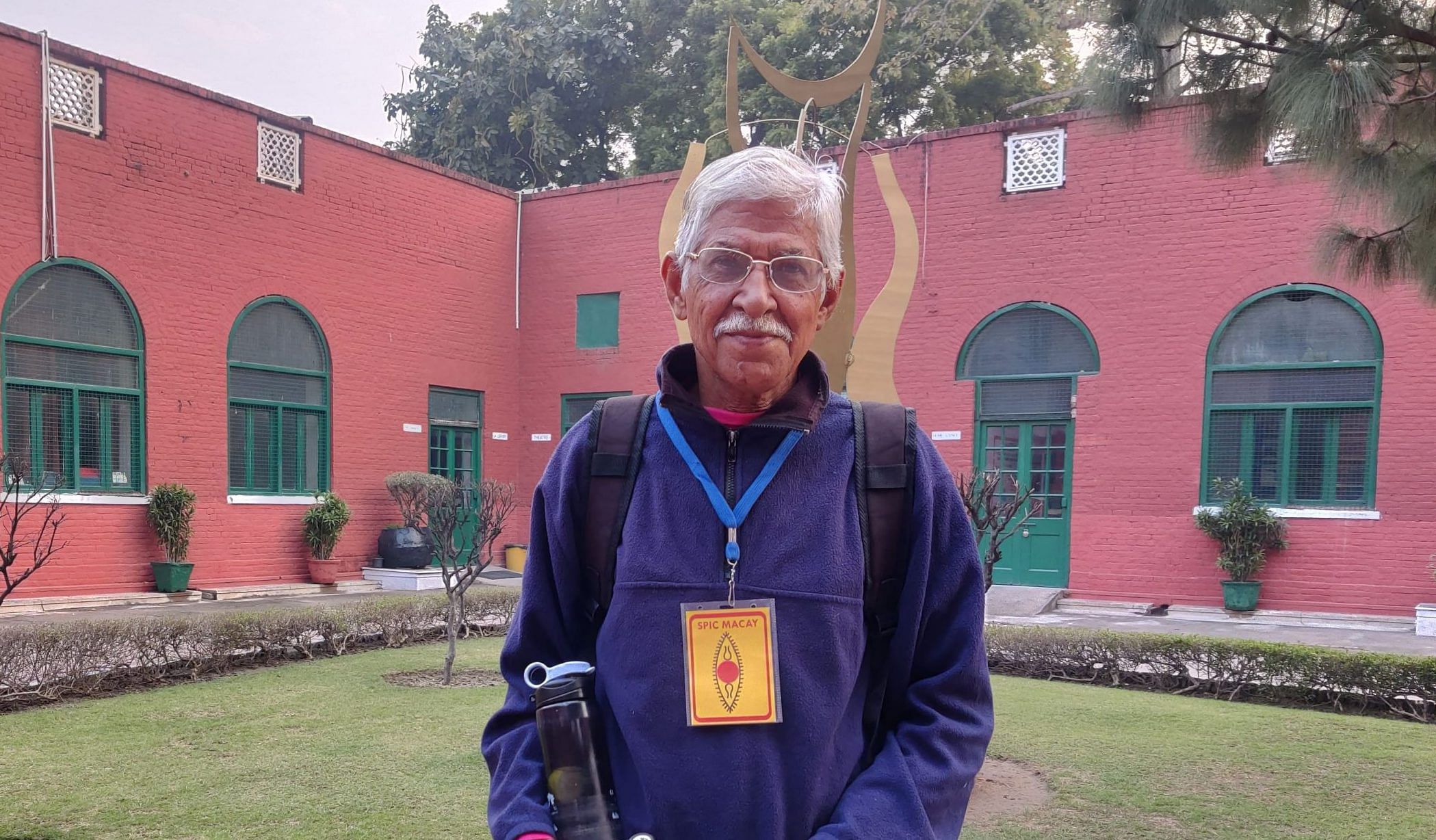

Kiran Seth, founder, SPIC MACAY

Seth had to borrow money to keep SPIC MACAY alive. Over time, however, it blossomed into a nationwide cultural movement. Now, at 75, with an army of over 2,000 dedicated volunteers, Seth knows that time is running out to pass on this rich cultural legacy to the next generation.

Battling anxiety with Raag Bhairav

SPIC MACAY holds its Saturday meetings at Modern School, Delhi, where everyone is welcome. The conference room, though often spilling over with young people, always finds space for those drawn to classical arts. Conversations hum, ideas float around, and then—just as the energy begins to settle—a frail, magnetic figure walks in.

In one hand, he carries a white-and-black Cannondale helmet; in the other, a few files and a black water bottle filled with sliced lemons. Kiran Seth. But the moment he speaks, frailty is forgotten. His voice, full of warmth, zeal and wit, cuts through the room.

He leads the meeting, acknowledging success and dissecting failures. He makes sure every voice is heard, listening with closed eyes. Criticism doesn’t rattle him. Seth continues to pedal forward, never letting the movement come to a halt.

Hariprasad Chaurasia told ThePrint that Seth never married because he was too consumed by his love for classical music and his mission to pass it on to the youth.

Seth’s unwavering belief in classical arts continues to drive him: “Classical arts teach concentration, patience, and creativity. They can take you to an alpha zone which cannot be easily described. It can ease your ‘monkey mind’.”

The philosophy rings true for many SPIC MACAY volunteers, especially Delhi University graduate Tannu Saini. Always restless, she struggled with self-doubt and the fear of failure, trapped in a cycle of anxiety. In her second year at Daulat Ram College, she found herself drifting into the world of came across SPIC MACAY. At first, she attended a few events just to keep herself occupied, having no idea how deeply it would eventually change her.

Saini wanted to be an actor and stand on the biggest stage in the world, holding an Oscar in her hands. “I was terrified that I wasn’t doing enough, that I wasn’t good enough. And that fear? It locked me inside my own room,” she said.

One day in January, during the regular Saturday meeting at Modern School, Seth suggested listening to different ragas according to the time of day and Saini decided to give it a try. She started with Raag Bhairav in the mornings. “At first, it was unbearable. The temptation to switch to a Bollywood song was so strong,” she said.

And then, something unexpected happened. The heavy fog of anxiety began to lift, replaced by a quiet clarity she hadn’t felt in a long time. The fear didn’t disappear overnight, but for the first time, she saw a way through it. Now, as she prepares for the FTII (Film and Television Institute of India) entrance exam, she carries the teachings of classical arts with her: discipline, patience, and faith.

“If you find svar (note) and laya (rhythm), consider it finding god. The whole world is yours then,” said flute maestro Hariprasad Chaurasia, a Padma Vibhushan awardee.

SPIC MACAY is no longer offering experiences and learnings. It has repositioned the role of music to that of a life coach.

Seth compares life’s inner journey to climbing Mount Everest. “If you could climb to the top, imagine the view, the feeling! Classical music has that power. It might even lower the chances of depression.”

Seth believes that we should be able to control our minds, but in the modern world, it’s the other way around. His solution is simple: “Let’s consider classical music as a technique, just a way to regain control over our restless minds.”

Also read: Indian shaadi checklist gets longer. Lehenga, mehendi & now pre-marriage counselling

SPIC MACAY’s journey

The 1980s was a heady decade. As Indians celebrated a young Rajiv Gandhi as prime minister and embraced the ‘mile sur mera tumhara’ brand of patriotism, Michael Jackson was blaring Bad on boom boxes. But that’s also the time when the good old Indian stuff was bubbling up.

College campuses in the big cities were witnessing a renaissance of sorts. Students packed into halls to enjoy SPIC MACAY events featuring Kishori Amonkar, Gangubai Hangal, Mallikarjun Mansur, Maharajapuram Santhanam, and TN Krishnan. Among some students, the events were cool to be seen at.

But it wasn’t easy.

In SPIC MACAY’s early days, Seth and his small team faced immense challenges. Cultural programs were dismissed as mere gana bajana and support was thin. Seth recalled sitting with a friend on Lady Irwin College’s lawns, planning artist schedules and logistics.

“It was like Waiting for Godot,” he laughed. With minimal backing, they often travelled with artists to ensure events happened as planned.

One unforgettable incident involved the legendary Hariprasad Chaurasia. “We thought everything was in place, Banaras Hindu University [BHU] was booked, and we had coordinated with everyone. But when Pandit Hari arrived, no one was there to greet him. Undeterred, he took a taxi to BHU, only to find no one knew about the programme,” Seth said.

The artist just drove back to Allahabad (now Prayagraj) and stayed there. “That was the reality then, people didn’t even recognise names like Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia,” Seth added.

Now, Chaurasia admires Seth not just for the man he is but for his relentless efforts in promoting classical art forms. “If I were the prime minister of India, I would have already honoured Kiran Seth with the Bharat Ratna,” he said.

Also read: NCPCR has been on an anti-madrasa campaign—to rescue Hindu children

First steps

The first decade of SPIC MACAY was a series of such struggles. “It was the commitment of a few who had been touched by this culture, who believed it was worth preserving. We just kept pulling the cart,” said Seth.

In ’80s, the first major cultural event SPIC MACAY had planned, Kiran Seth found himself in a tight spot. The programme was set to span nine days across Delhi’s top institutions, featuring legendary artists like Bhimsen Joshi and Ustad Bismillah Khan. Everything was in place, but there was one crucial thing missing: the funding. With just two weeks to go, Seth realised they might have to cancel the entire event.

One Sunday afternoon, riding down Tughlaq Road, Kiran spotted a nameplate—P Sabanayagam, Secretary of Education. On impulse, he rang the doorbell. A woman answered, and he insisted, “I need to meet him. It’s urgent.”

After some back-and-forth, Sabanayagam agreed to meet him in his office. Kiran laid it out: The event was at risk without Rs 25,000. Sabanayagam simply said, “We’ll try and support you.”

To Kiran’s surprise, the grant was approved on the spot. It was a turning point for SPIC MACAY—the first cheque received from the Government of India.

In 1979, SPIC MACAY embarked on its first Lec-dem Series. Teaching and learning was part of the performance from word go—artists routinely paused to explain raag, taal, laya, and mudra to the audience. The lineup was legendary—Birju Maharaj, Sonal Mansingh, Amjad Ali Khan, Munawar Ali Khan, Asad Ali Khan, and many more of India’s finest artists.

“Six of the most renowned artists were coming, and we had coordinated with the institutions. But when I went to Lady Shri Ram College, the principal asked, ‘How can we do this during lunch break?’ These were her exact words. They had no idea who these artists were. The ignorance was overwhelming. The top artists in the country were barely known, and it was a struggle to even get the institutions on board,” Seth said.

Seth and his team searched the city for venues, finally securing three: Lady Irwin College, Miranda House, and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). Convincing the hosts wasn’t easy, but JNU’s Godavari Hostel Mess proved to be an ideal choice. “We did the programme in a mess, and it was fantastic. It had that raw, intimate vibe. The beauty of classical music lies in its intimate setting,” Seth said.

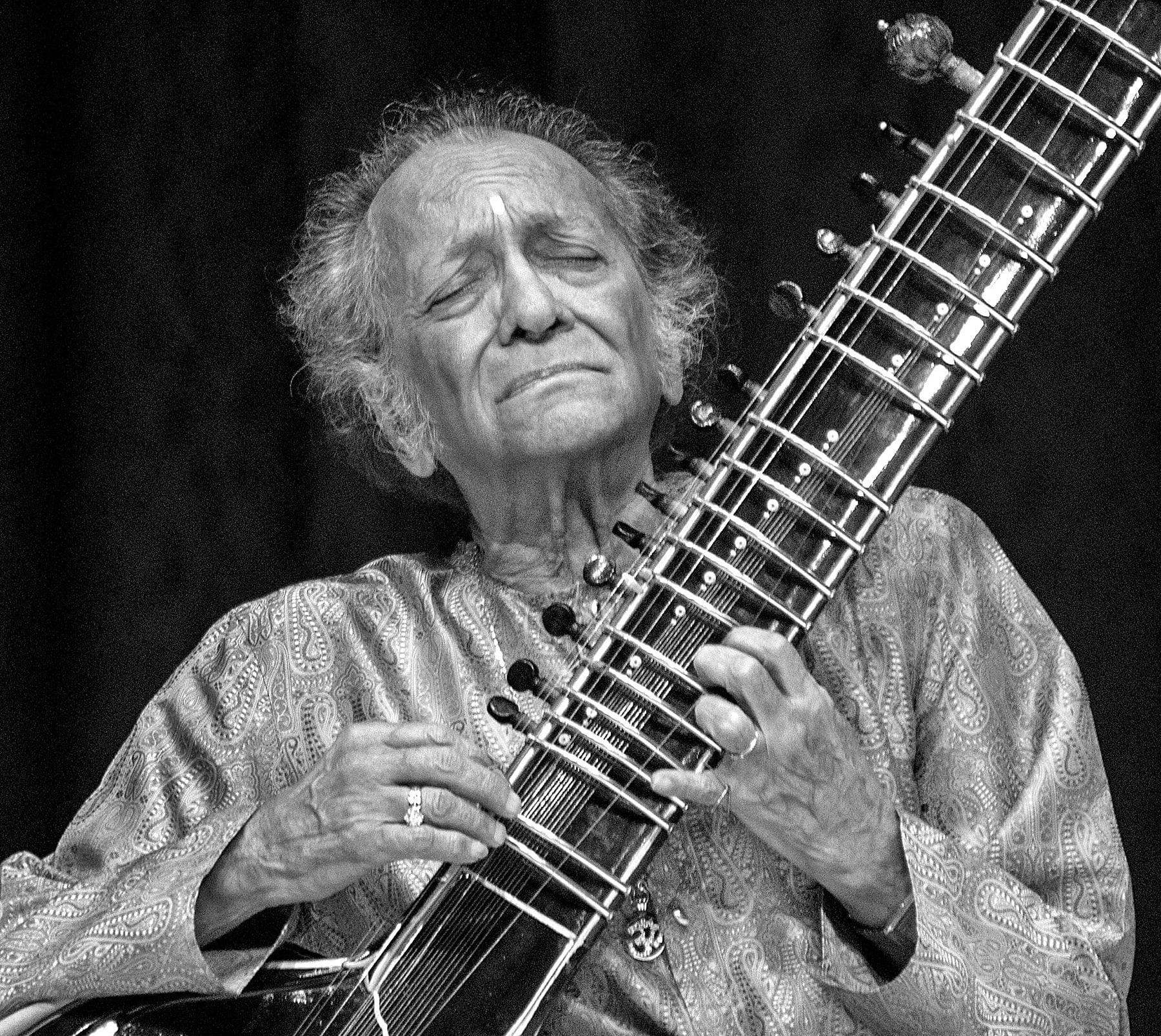

Bharat Ratna awardee sitarist Ravi Shankar once said that classical music survived because of baithak circles—small groups of people gathering to enjoy music, not in grand auditoriums but in humble domestic spaces.

“In large auditoriums, with the artist distanced and sound amplified, something shifts. Art isn’t one-way traffic; the audience’s energy shapes the artist just as much. A single harkat (musical expression) can change a performance. That connection is what makes smaller settings so special,” said historian Vikram Sampath.

Also read: I was a pregnant penguin, see my before-after pics. 66-yr-old’s Ozempic to Mounjaro journey

A transformative power

SPIC MACAY wasn’t just about performances; it became a bridge between legends and learners. Through the Gurukul Anubhav Scholarship, students could grow under the mentorship of great artists, experiencing the essence of India’s artistic heritage firsthand.

Some moments stay with you, and only much later do you find the words for them. It changed my life, taught me that knowledge isn’t about facts, it’s about sadhana (devotion). SPIC MACAY is imprinted on my soul.

Oroon Das, theatre artist and performer

In 1989, a young 10th grader Oroon Das, now a designer and multidisciplinary artist, found himself attending SPIC MACAY’s Gurukul Anubhav Scholarship Scheme. Back then, students trained under renowned classical artists, immersing themselves in their world.

“There’s a stream of consciousness that flows through classical art forms. You only realise its depth when you’re in the presence of those who have dedicated their lives to it,” Das told ThePrint.

SPIC MACAY uses Vedic Gurukuls across India as venues for its programmes. At the Dhrupad Gurukul in Panvel, Das’ mornings began with riyaaz (practice) at dawn. “We didn’t always know what we were doing, but we kept at it,” he said.

Khandala’s waterfalls were visible from the Gurukul’s terrace. Das spent a month learning from Guru Zia Mohiuddin Dagar, absorbing not just music but the very essence of the guru-shishya tradition. When he returned home, something had shifted within him. Two years later, his guru passed away.

“For two years, I couldn’t sing. It felt like a vital link had broken. I kept searching for another guru, another home. But losing him left me incomplete,” he said.

SPIC MACAY, Das said, offered more than training. It was an immersion, a surrender. That one month shaped him in ways he only understood years later.

“Some moments stay with you, and only much later do you find the words for them. It changed my life, taught me that knowledge isn’t about facts, it’s about sadhana (devotion). SPIC MACAY is imprinted on my soul.”

Das is not alone in feeling this profound impact. Across cities and generations, the movement has transformed lives in ways its participants could hardly have imagined.

Vikram Sampath’s story is no different. Growing up in Bangalore, he was immersed in Carnatic training from age five, but his path to deeper artistic discovery took its own shape under SPIC MACAY’s influence.

Also read: ‘Educated Dalits’—how these two words swung Bombay HC landmark verdict for 2 JNU scholars

Finding gurus at SPIC MACAY

At BITS Pilani, organising SPIC MACAY concerts, meeting artists, and attending workshops expanded Sampath’s world beyond Carnatic. He describes it as “moving from narrow lanes to the highway of art”.

SPIC MACAY brought Sampath his greatest gift—his gurus. After a concert, Bombay Jayashri heard him sing and was stunned. “What are you doing in an engineering college? Be my student,” she said.

He accepted instantly, training under her in Chennai during vacations. Later, on Jayashri’s advice, he continued his journey with veena maestro Jayanthi Kumaresh, staying connected to his Bangalore roots.

“I owe so much to SPIC MACAY, personally, for getting my two gurus, to whom I owe so much, and for the sheer exposure to other art forms,” he said.

Even after leaving BITS Pilani in 2003, Sampath started a SPIC MACAY chapter at SP Jain Institute of Management & Research in Mumbai.

“Once you’re in it, you can’t get out easily,” he said. “If a young person is ready to receive, SPIC MACAY offers a Niagara Falls of art that pours over them.”

SPIC MACAY’s influence extends beyond students; for Carnatic vocalist Sudha Raghuraman, SPIC MACAY has been more than a stage. It has shaped her as a musician, an educator, and even as a mother.

“When I started SPIC MACAY concerts, my son was very young. Interacting with students taught me to understand young people better, which strengthened my bond with him. More concerts, more children, more experiences—you bring it all back home. Music is there, and here too,” she said.

“It has taught me patience, humility, and the power of giving without expecting anything in return. When you walk into a school and see hundreds of children waiting with open hearts and minds, you realise that you are merely a vessel for something much greater.”

Raghuraman has performed on grand stages, but some of her most unforgettable moments have come from the humblest settings.

She laughs, recalling the questions students would ask her: “How long will it take for me to sing like you?” “Why did you choose this?” “Do you sing Bollywood songs?” But with the amusing questions came some more sincere ones too: “How many years does it take to master this art?” “What’s the difference between Hindustani music and Carnatic music?”

In a remote school by the Bhagirathi River in Uttarkashi, she once sang as teachers wept—moved by something they couldn’t quite put into words. Then there was a small school in the heart of Ujjain’s villages, where she performed without a stage in front of students who wore no uniforms or shoes.

“I stood there, watching them, tears in my eyes. That we could bring music here, to this moment—it is only because of SPIC MACAY,” she said.

Also read: Real story of Naga sadhus. Kumbh’s rockstars watch T20, OTT, reels, don’t live in caves

The present challenge

Kiran Seth has spent decades championing India’s artistic heritage, but as he looks around today, he says he feels both pride and unease. The SPIC MACAY he built was rooted in passion—more heart than money, as he puts it. Now, funding isn’t that big of an issue. Commitment is.

He believes cultural events have shifted from deep experiences to flashy spectacles. “It became about size, not substance. Artists like Birju Maharaj and Bismillah Khan could move audiences with a single note. Today, that emotional resonance is missing. People no longer distinguish between diamonds and glass,” he said.

For Seth, the real challenge isn’t just access; it’s inspiration. He said that the role of a teacher or an artist goes beyond communicating information—it’s about igniting a spark.

“When I was a student, our teachers were inspired. Today, it’s a profession, not a calling. And the passion of a true teacher or artist is what’s missing. The internet can’t give you that,” he said.

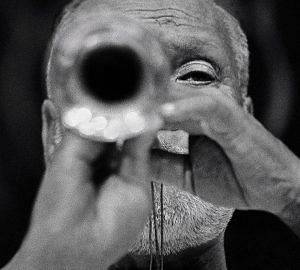

Photojournalist Raghu Rai agrees with Seth. Though he never formally learned to sing, SPIC MACAY was a way for him to connect with classical music. He would often ask the maestros to sing or play entire ragas and capture their meeting with divinity on his camera.

“Back then, music wasn’t just a show; it was an offering,” said Rai. “Artists closed their eyes and themselves in the melody, and when they reached that divine connection—that’s when I clicked. But for music to touch the soul, there must be penance—tapasya. Without it, the surrender, the divinity—it fades. Today, concerts are shorter, fewer, and it’s not the same.”

Also read: A Tamil Nadu mill is also a college. Workers graduate & get jobs in Tata, Mahindra

An enduring legacy

Every movement has its moment, a time when it fills a crucial gap, addresses a need, and carves out its purpose. And according to Sachchidanand Joshi, Member Secretary of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), SPIC MACAY was born in such a moment.

In the 1970s and 80s, classical music wasn’t easily accessible. For students at IITs and IIMs, the world of maestros like Hariprasad Chaurasia, Shiv Kumar Sharma, and Amjad Ali Khan was distant—almost unreachable. SPIC MACAY changed that.

“For many, it was their first encounter with maestros, artists they couldn’t have seen even if they had paid a thousand rupees for a ticket,” Joshi said, highlighting that its legacy cannot be erased.

Legends performed not for money, but for the sheer belief that art must be passed down, instead of being locked away in exclusive circles.

This democratisation of culture had a lasting impact. Joshi sees it in the way thousands of people, decades later, still recall their first SPIC MACAY experience as something life-changing.

But time has moved forward. The need has changed, and so has SPIC MACAY. Music is everywhere, streaming at the tap of a screen. The problem today, Joshi argues, is discernment. The digital age has flooded the world with content, making it harder for students to distinguish between the profound and the fleeting.

Yet, the legacy of SPIC MACAY endures. It continues to introduce young minds to a world that, once entered, changes them forever. The question now is not just how to preserve that legacy, but how to make it thrive in a world that is shifting faster than ever.

Faiyaz Wasifuddin Dagar has high hopes for SPIC MACAY and envisions a future where young people engage with classical music in a way that feels natural and accessible. “Why can’t we have a dedicated radio channel for Indian classical music? A space where anyone seeking peace can tune in anytime?” he said.

Seth maintains that his mission is far from complete. Travel to small schools and colleges, he says, and you’ll see how much is still left to do. Many students today wouldn’t recognise names like Bhimsen Joshi, Bismillah Khan, or Ravi Shankar.

“We’ve barely scratched the surface. Our cultural treasures are fading from memory,” he said.

Seth continues to urge volunteers to find ways to weave classical music into everyday life on their campuses. He envisions schools, colleges, and even hospitals incorporating ragas at specific times of the day to cultivate mindfulness and well-being—an idea already adopted by IIT Kanpur, with efforts underway to introduce it at Delhi Technological University (DTU) and beyond.

He shared a powerful thought that stuck with him throughout his journey—a quote from Ustad Rahim Fahimuddin Dagar: “Nadi ke kinare khade ho karke, nadi ki gehrai ka andaaz nahi hota hai (standing at the edge of a river doesn’t tell you how deep it is). It’s only when you immerse yourself in it, do you realise how little you know.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)