Jaipur: At 6:30 on a cold November morning, Gajanan Jangid found himself standing on the railway tracks near his home in Rajasthan, staring at a body in a white checked shirt and blue trousers. Minutes earlier, the police had called asking him to identify a corpse. It was his older brother, Mukesh Jangid, a booth-level officer (BLO), who had spent nearly a decade doing what was considered routine electoral work. Before the shock could settle, a constable nudged him: “Check his pockets.” From the blood-stained clothes came a key, a Rs 500 note and a handwritten letter with just five lines that carried the weight of weeks of crushing SIR workload – digital deadlines, repeated rejections and mounting threats of suspension.

“I am BLO Mukesh Jangid. I am very frustrated with SIR work. I couldn’t sleep all night. My supervisor has been giving threats of suspension. This is why I am committing suicide,” Mukesh, 47, wrote in the note, three days before stepping in front of a train at Bindayaka railway station, 15 km from Jaipur.

Mukesh, the BLO of booth 175 in Jaipur’s Jhotwara, was a teacher at Naari ka Baas government school. He had barely slept in the last three days, according to his family. On November 16, he left his home at around 4 am on his motorcycle, parked it near the railway station, and never returned.

India’s voter roll revision is meant to be a bureaucratic exercise – clerical and procedural. But the second phase of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) has turned into a grinding machine pulling thousands of teachers, BLOs, and ground-level staff into a vortex of impossible deadlines, glitching apps, and a 2002 voter list they must now resurrect form by form, without much training. Across at least five states, it has set off a trail of suicides, hospitalisations, resignations, complaints, and breakdowns.

For many, the work has begun to feel less like a civic duty and more like a detonator – one that, in a few cases like Mukesh’s, has gone off.

And Mukesh is not alone. Another BLO from Rajasthan recently died of a heart attack on duty, his family alleging the same pressure that shadowed Mukesh. In Uttar Pradesh, a 47-year-old BLO Sarvesh Kumar Gangwar collapsed and died while on duty, his family blaming the “immense pressure” of SIR work. Two other BLOs, from Kerala and Bengal, also ended their lives a week ago; their families, too, point to the immense workload.

These incidents, spread across states, trace the outline of a system pushing its lowest rungs past endurance.

The work that didn’t stop

The Jangid home sits at the centre of a wide, sandy courtyard; its unfinished, two-storey cement frame stark against the sky. On the eleventh day after Mukesh’s death, more than twenty people sit scattered across the courtyard on plastic chairs outside his house; mattresses laid out under a makeshift canopy for mourners who may drop by.

The men outside discuss how the work that pushed Mukesh over the edge continues without pause even after his death.

Inside, women in bright red, yellow and orange sarees huddle in a single room, murmuring about the future of Mukesh’s two young daughters. His wife lies curled on the floor, behind his mother, exhausted.

For 15 days before his death, Mukesh had shifted from waking at his usual 7 am to getting up at 4. He spent the early hours mapping his day, calling electors, and re-uploading offline entries on the BLO app, often repeatedly because of glitches and his limited digital skills.

His 11-year-old son recalls falling asleep while watching his father work and waking up to find him still bent over forms. His daily target was 200.

“He did everything but still the supervisor said he was constantly making errors online. He had to do things twice, even thrice,” Revanshu said, his head covered with a handkerchief shaved for mourning, customary in Hindu traditions. He had tried to help his father with online work but it was not enough.

An assistant was tasked to help Mukesh with the workload, but that too backfired. “My father had to correct his work, too, late at night,” the boy added quietly.

Mukesh’s father, Nanakram, last spoke to him two days before he died. On the call, Mukesh had spoken about his supervisor and the intense work pressure.

“I told him not to worry and to do what he could. I didn’t know he was in so much trouble,” the 70-year-old said, wiping tears.

Mukesh’s daughters, who took over all the household chores in his absence, are struggling to understand his decision. They are angry with their father for not sharing his burden.

“But men never share their failures with their families – they have to be strong. That pretending has left us without a father,” Kunjal, 23, said.

No officer visited the family after his death to offer condolences, his relatives claim. But the forms had to be collected, and someone had to replace him. Even Mukesh’s successor at work was reluctant to take the job – “like being handed a bomb,” his colleagues said.

A workload built on impossible questions

At the heart of SIR is a near-impossible task: BLOs must trace where each elector voted in 2002. For migrant families, daily-wage workers, or women who married into new villages long after, this is information they simply cannot produce.

Often, BLOs leave the 2002 column blank, fill whatever secondary details they can gather, or call colleagues in other villages for help. But many trails run cold, leaving forms incomplete and BLOs like Mukesh stuck in loops they cannot resolve.

“He had to call BLOs in the (married) women’s villages to get their old details and photos,” Revanshu said. “But he wasn’t successful in every case.”

A new 18 November deadline – set by Mukesh’s supervisor – for a subset of forms pushed him over the edge. The official deadline is 4 December.

“The work he did before was dismissed by the supervisor. He called his friend for help and did it again, but the supervisor didn’t approve of that either,” the boy added.

Another BLO, same problems

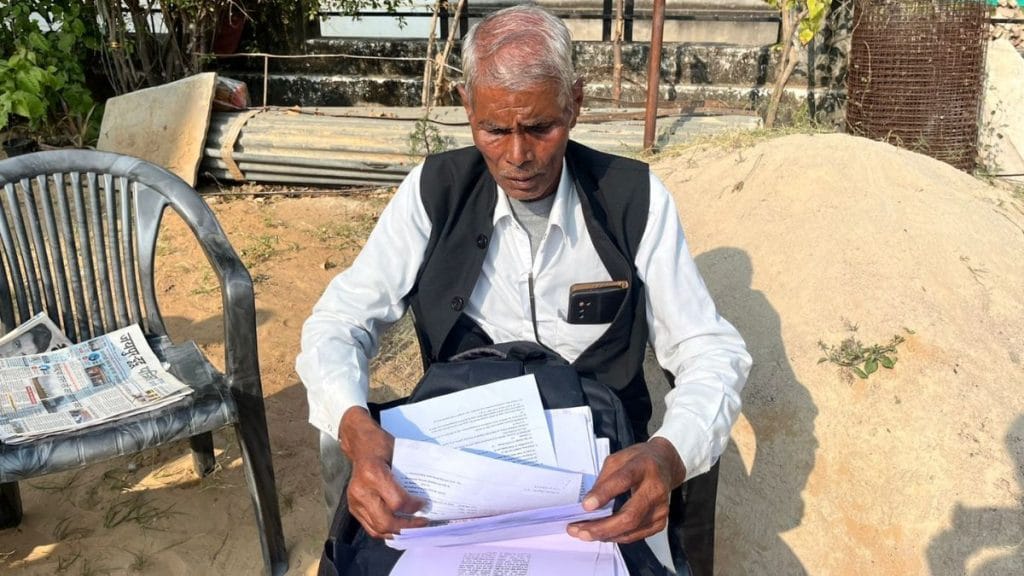

In Sanganer, 32 km from Mukesh’s home, another BLO is chasing people, forms and memories of 2002 across a fast-growing settlement of migrants and new homeowners. The neighbourhood is a maze of narrow, neatly swept lanes, bright blue and red iron gates, pastel homes and motorcycles weaving through.

Dressed in a blue shirt, black half-jacket and thick glasses against the early winter chill, Awasthi, who wanted to be identified only by his surname, moves from one home to the next – with forms in one bag, food in another – with a fellow teacher assigned to help him. Many residents of the locality are daily-wage labourers or factory workers who leave for work by 8 am. If Awasthi doesn’t catch them before that, he must try again later.

His constituency is falling behind; he has received a notice.

His target: 200 forms a day – just like Mukesh – all uploaded at night when the app works better. He wakes up at 5 am daily, uploads forms till 7 am and rushes out by 7:30. He walks, takes his motorcycle and even waits for hours at people’s homes.

“I’ve been working constantly for a month but still I’m behind. People have come here from other states. They don’t have 2002 details,” a tense Awasthi said, arranging forms at 6 pm, his day’s target still unmet. People don’t cooperate in the evening; everything has to be completed before dusk.

“There are many practical problems on the ground which seniors don’t understand,” he added.

He receives more than 100 calls a day from electors, supervisors, and people confused by the forms.

“They don’t remember in which constituency their father voted in 2002. And we can’t cut their vote because they are Indian citizens,” Awasthi said.

Then there are the “bulk voters” – Banjaras and Ghumantus with no fixed address. Awasthi claims there are “hundreds” of such cases.

“I can’t even cancel the IDs. I have to paste a notice on their houses but the address column says zero,” he said, holding his head.

By 5 pm, Awasthi had covered 50 houses. At one home, 23-year-old Mohit Singh opens the door, frustrated. This is his fifth visit and Mohit still hasn’t found his father’s 2002 voting details.

“Someone has to go to the old landlord in Delhi to get the details and I don’t have time. I will go this weekend,” he said. Awasthi flushed red. Mohit continued without waiting for a response.

“The deadline is 4 December so we have time. You can’t cut my name from the voter list, it’s my right,” he added before shutting the door.

Awasthi smiled and moved on to the next house.

“Sometimes I feel like banging my head on the wall,” he said.

He still had hours of uploading left.

Also Read: Pause ‘wasteful’ SIR until an audit with public hearing—ex-IAS writes to poll panel amid BLO deaths

‘We were hired to teach’

In Uttar Pradesh’s Hathras, primary school teacher Rami Kumar walks through village lanes handing out forms while worrying about her empty classroom. She teaches Class 4 students in the local government school.

“Exams are here and half my syllabus is pending,” she said. “I was hired to teach. But I’m in field work now.”

In Rajasthan, exams have already begun last week amid approaching SIR deadlines. Teachers say they are drowning in work.

There are around 61,000 BLOs in the state and over 50,000 of them are teachers.

“The selection is random,” Vipin Pandey of the Jaipur Teachers’ Association said. “Five teachers from one school may be picked. Three go to the DM office to remove their names, but they ask them to suggest a substitute, so another teacher gets added.”

Payment is meagre: Rs 500 a month for regular BLO work, about Rs 6,000 annually for SIR, and Rs 6,000 for routine duties.

Pandey himself cannot locate his own old voter ID from 2002; he has since moved cities.

“Imagine the difficulty for uneducated people; they won’t make any efforts,” he said. “No one knew in 2002 that they would need their old voter IDs in 2025. Every teacher working on this is frustrated.”

Across states, the strain has reached official complaints. In UP’s Gautam Buddha Nagar, the Primary Teachers’ Association submitted a memorandum to the District Magistrate this week accusing officials of “mental harassment” of teachers deployed as BLOs. It also accuses officials of responding with FIRs and adverse entries instead of support when the teachers reached out to them.

“We have requested the administration to withdraw the FIRs, cancel the adverse entries, and stop the mental harassment of the teachers, and ensure that senior officers cooperate with the BLOs and ensure the work is completed in a dignified manner,” Praveen Sharma, District President, Uttar Pradesh Primary Teachers’ Association said.

Even RSS-affiliated Akhil Bharatiya Shaikshik Mahasangh has written to the Election Commission criticising the scale and pace of SIR. The body called the workload “unethical” and said teachers deployed as BLOs were facing “pressure and intimidation”, demanding both an extension of the deadline and Rs 1 crore compensation for families of BLOs who died during the exercise.

Childhood dream lost

Back in Mukesh’s home, his daughter Jyoti, 25, has locked away his school books. She had been preparing to become a teacher, just like her father but not anymore.

“I didn’t just lose my father. I lost my childhood dream of becoming a teacher. I wanted to teach, not do fieldwork with stress and deadlines,” Jyoti lamented, covering her face with a dupatta (veil) drenched in tears.

Now, she is looking for another career path. “I don’t want what happened to my father to happen to me.

(Edited by Stela Dey)