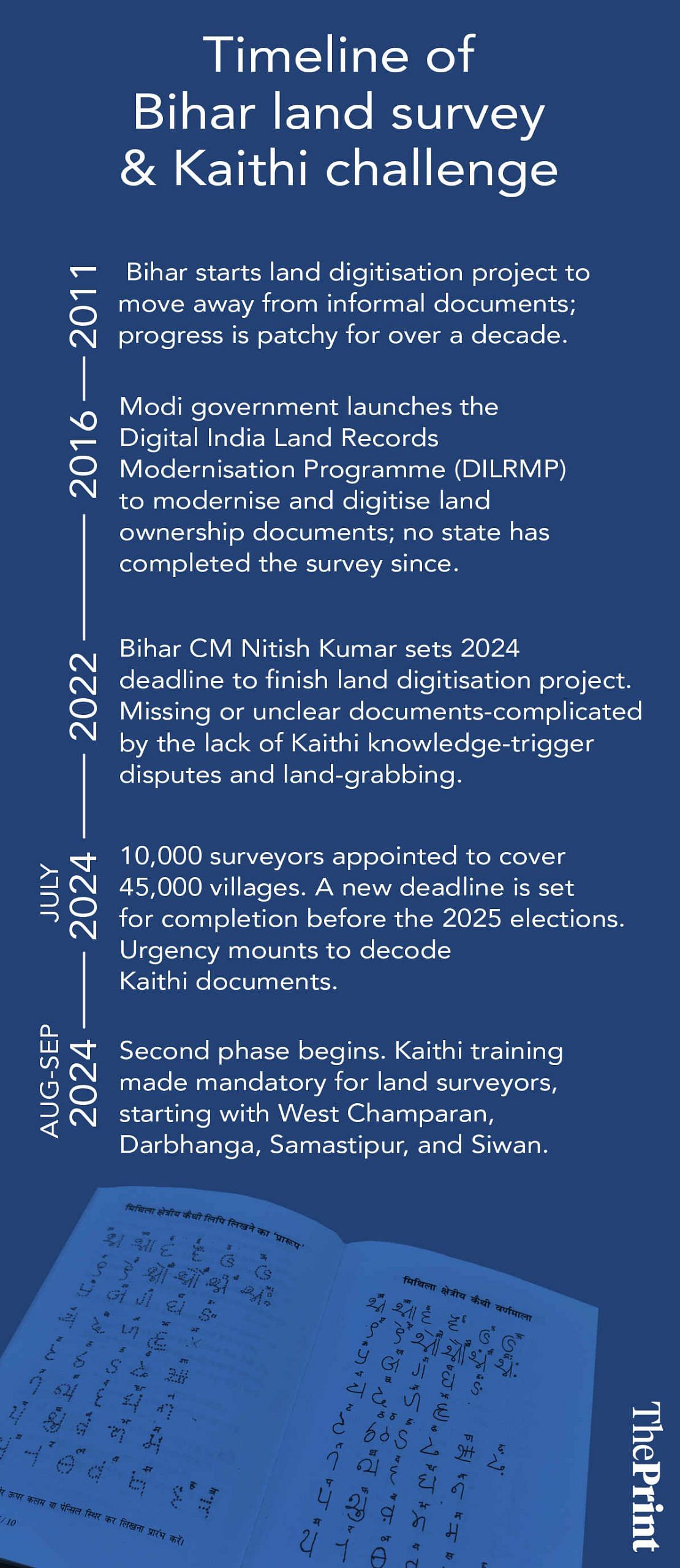

Samastipur (Bihar): As rain lashed down, 26-year-old land surveyor Deeplal Kumar biked 20 km from Bibhutipur to Samastipur, not to measure plots but for a tough new job requirement— a crash course in the nearly extinct, 1,000-year-old Kaithi script. Instead of using machines and compasses, civil engineers and surveyors are now back in classrooms, learning to read old documents written in Kaithi to meet the 2025 deadline for the Bihar land survey.

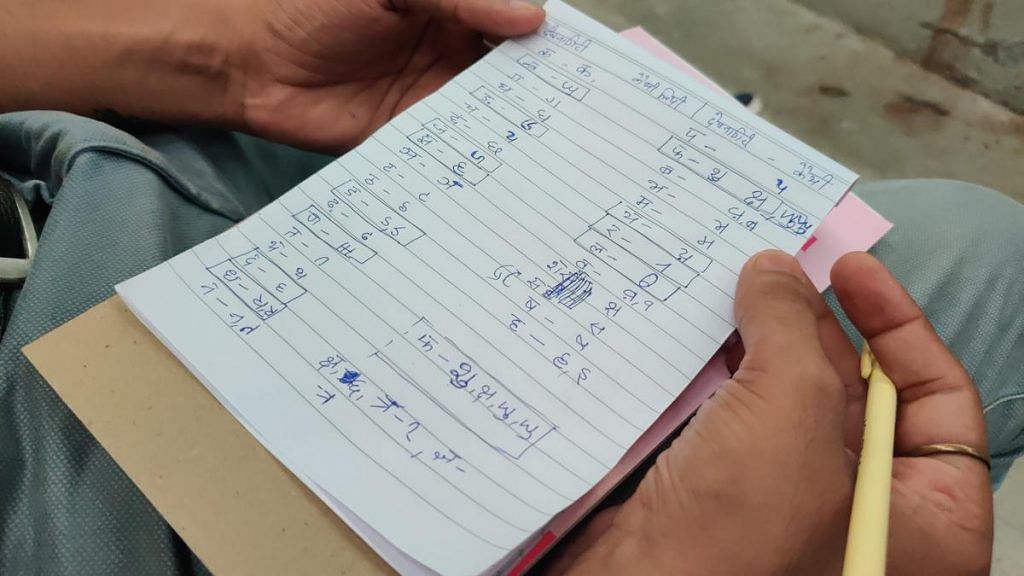

“Most of the old land records are in Kaithi. Without learning this, land survey work can’t be done on the ground—and hardly anyone understands it,” said a drenched Kumar, arriving at Samastipur’s District Registration and Counselling Centre for a three-day Kaithi training session organised by the Directorate of Land Records and Survey from 26 to 28 September.

Kumar is one of 10,000 surveyors appointed this year by the Nitish Kumar government to map 45,000 villages and finally bring order to Bihar’s tangled land records. The goal is to digitise decades of chaotic paperwork and slash property disputes, which reportedly drive up to 60 per cent of the state’s crime. With assembly elections due next year, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has fixed a July 2025 deadline to get the job done. But just as the second phase of the land survey picked up speed in August, Kaithi became the genie let out of the bottle.

The ancient, nearly forgotten script is now haunting everyone from landowners to officials, and the government is rushing to get a handle on it.

The lack of Kaithi knowledge has led to mounting frustration at district offices, where stacks of crumbling documents gather dust on desks and queues snake out the door. Surveyors, clerks, and landowners wait impatiently for the few translators available to squeeze them in. The opposition has been quick to pounce too, accusing officials of corruption and blaming the government for deepening the struggles of the masses. In all this, Kaithi has become both a thorn in the side and the catalyst for reviving a cultural legacy.

People are ready to live or die for every inch of land. Once the records are made online, many issues related to land will end

-Jai Singh, secretary of the Land Records and Survey Department

To tackle the bottleneck, the Bihar government rolled out Kaithi training sessions for surveyors in September, the first time such efforts have been made statewide. So far, classes have been held in West Champaran, Darbhanga, Samastipur, and Siwan districts, with the next round planned for Saran, Munger, and Jamui. But experts warn that a few days of training barely scratches the surface.

“In three days, this script can only be read and written in a basic manner. It’s not a guarantee of fully learning this old script, which once ruled the masses and courts,” said Pritam Kumar, a Kaithi trainer in his 20s. Hired by the government to hold sessions for surveyors over three months, he’s also pursuing his PhD in the script at Banaras Hindu University (BHU).

Helping Pritam in the Samastipur session was 20-year-old Waquar Ahmad, the only other Kaithi trainer appointed to teach surveyors. While Pritam teaches the basics—letters and simple sentences—Ahmad focuses on reading the land documents.

But Kaithi alone isn’t enough to decipher the land records, pointed out Ahmad, a zoology student from Chhapra who learned Kaithi from his grandfather. Many documents are also laced with Urdu and Persian terms.

“It’s important to know these (Urdu and Persian) words, along with Kaithi—only then will the survey work speed up,” said Ahmad.

“Kaithi translators used to charge Rs 200-300 per page. Now it’s Rs 1,000-1,500,” said Arvind Kumar, who runs a photocopy shop in the Samastipur district court premises.

Also Read: Bihar district courts are swamped with new disputes as land digitisation begins

Kaithi 101

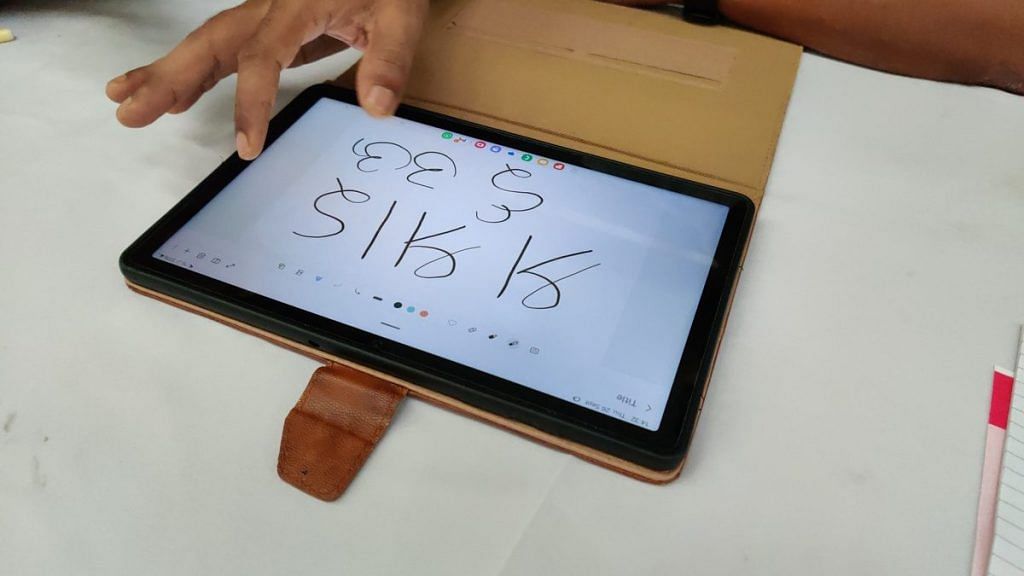

Around 270 land surveyors and district revenue officials sat shoulder to shoulder on stainless steel chairs in the whitewashed hall of Samastipur’s DRCC, sipping tea and staring at a 44-inch LED screen. This was their government-mandated boot camp in Kaithi, comprising three eight-hour sessions .

Every time trainer Pritam Kumar drew a letter of the ancient script on his digital pad, it flashed on the screen.

“Kaithi is not considered the script of a prosperous society. It has been the script of the common people—hence it was called jan lipi (people’s script),” Kumar told the group over the hum of stand fans and the crackle of a malfunctioning microphone.

He then pulled up old land documents written in Kaithi, noting that until independence, many people were proficient in reading and writing it. In fact, the last major land survey in Bihar—conducted about 100 years ago—was recorded entirely in Kaithi, and the script was still used in the years that followed.

The surveyors jotted down notes, some looking bewildered as Kumar guided them through simple words like kalam (pen) and khatiya (cot), written in the script.

“In Kaithi, grammar isn’t given much importance, and it doesn’t use conjunct letters like Devanagari does,” he added.

Much like a school classroom, this one had ‘backbenchers’ too. Laughter broke out when one trainee joked about writing letters to his seniors in Kaithi. Some chatted and took calls as the lesson went on.

Others, especially the women, were more attentive, practising writing their names and proudly showing each other their results.

But with eight hours to get through, impatience started creeping in.

“After studying for years, I got a job and now it feels like I am back in primary class,” complained one trainee, speaking on condition of anonymity. “I never thought that I would have to learn a script that is hundreds of years old. It’s an extra burden on us.”

Those who could read Kaithi have now grown old. So, it is necessary to nurture new people so that the disputes related to the script can be resolved

-Professor Ram Sevak Singh, Tilka Manjhi Bhagalpur University

Still, there’s no escaping Kaithi. In Bihar, almost every household has old documents written in it. And as the trainees settled into the rhythm of the lessons, some became more engaged.

“Learning Kaithi is an interesting and unique experience. It helps in reading documents that have never been read before,” said Anand Kumar, a land surveyor.

For the Bihar government, this training is the key for solving the fresh wave of property disputes that arose after the land survey started.

In his Patna office, surrounded by stacks of land files, senior IAS officer Jai Singh, secretary of the Land Records and Survey Department, told ThePrint that while awareness of land issues has grown post the survey, Kaithi is the stumbling block.

“So, there is a lot of fuss,” said Singh. Having spent years working on CM Nitish Kumar’s digitisation project, he argued that Kaithi training will pay off in the long run.

“The department will have its own Kaithi resources,” he said. “At present, problems are being faced because land is a sensitive issue. People are ready to live or die for every inch of land. Once the records are made online, many issues related to land will end.”

Believed to have been developed between the 6th and 10th centuries, Kaithi had its golden age during the reign of Sher Shah Suri in the 16th century, when it was used in his royal court and even appeared on official seals.

Glory to decline

Kaithi was once far more than just a script for land records—it appeared in folk songs, temple inscriptions, and even the personal letters of Bihar’s freedom fighters. But it started declining in the mid-19th century, as Devanagari became the dominant script for Hindi dialects.

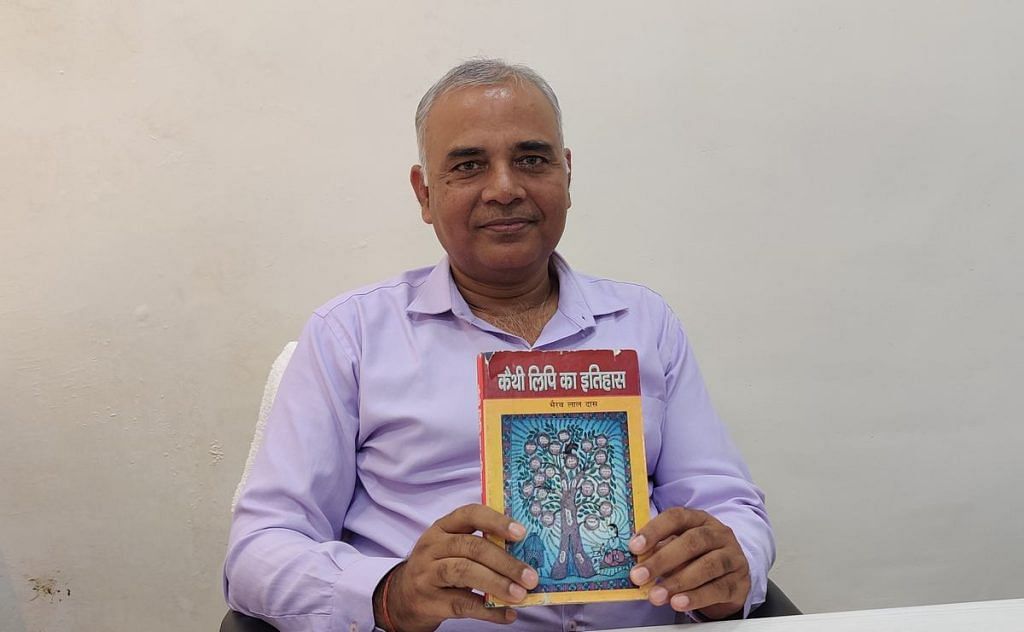

“Kaithi was the soul of Bihar’s culture. A lot has been written about it in history,” said Bhairab Lal Das, a project officer at the Bihar Legislative Council and author of the 2007 book Kaithi Lipi Ka Itihas, which traces the history of the script.

The exact origins of Kaithi are debated, but Das, who is also a historian, said that it developed during the disintegration of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century. As new regional powers, or satraps, emerged, a need for local scripts arose, and Kaithi was fully developed between the 6th and 10th centuries.

“Evidence is found in temple inscriptions, folk songs, and land records,” Das said, adding that regions like Magadha, Bhojpur, Tirhut, and Mithila each developed slight variations of the script. Inscriptions have also been found in Rajasthan, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh.

Much of this material, however, remains understudied.

“No archaeologist has written about it and serious research is yet to be done,” said Shiv Kumar Mishra, curator of the Begusarai Museum and editor of the research magazine Mithila Bharti.

If people learn Kaithi only to read land documents, then it will be injustice to this script. Take any step into history, and you will find Kaithi there.

-Bhairab Lal Das, author and Kaithi expert

The experts agree that Kaithi had its golden age during the reign of Sher Shah Suri in the 16th century, when it was used in his royal court and even appeared on official seals. The script’s use continued under the Mughals, but its use started dwindling during British colonial rule. By independence, Kaithi was fading from daily life.

“Just a century ago, this script was more known and popular than Nagari,” Professor Alok Rai wrote in his 2001 book Hindi Nationalism, adding that even among Hindi experts today, it’s rare to find anyone who can read or write a single line of Kaithi.

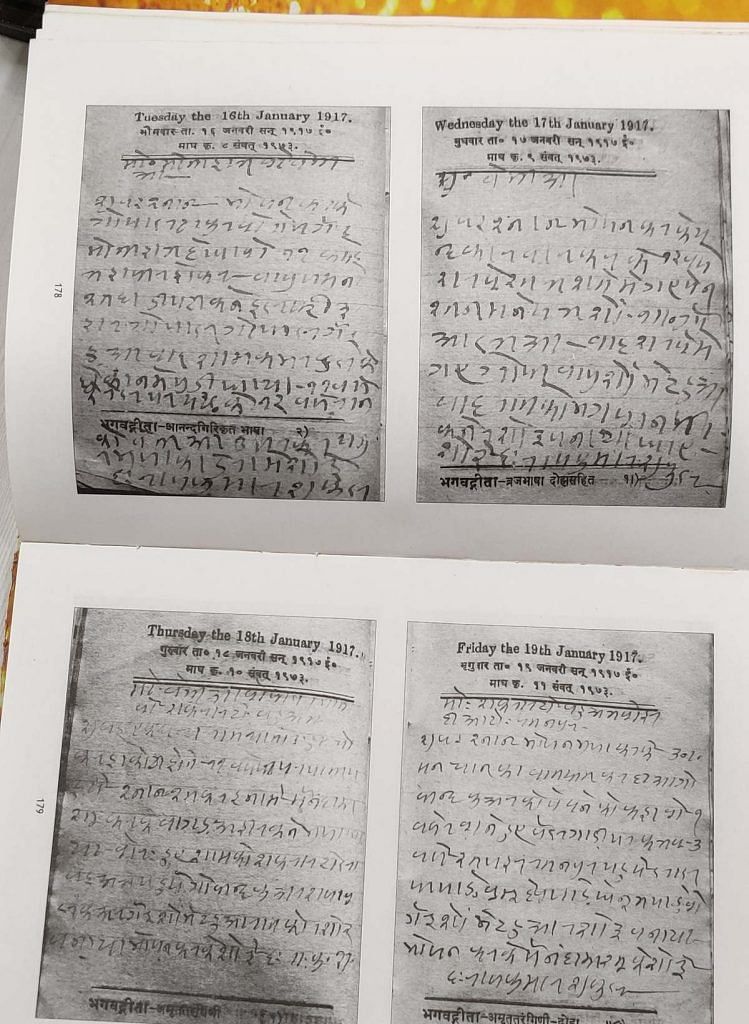

This is a loss to historical and literary research, according to Das. For instance, while researching the script, he stumbled across the diary of Rajkumar Shukla—the man who famously brought Mahatma Gandhi to Champaran in 1917, leading to the Champaran satyagraha of indigo farmers.

“Shukla was described as illiterate by Gandhi’s biographer Louis Fischer, but he knew how to read and write Kaithi and used to write his diary in this,” said Das, who transcribed it into Hindi.

Gandhi himself mentioned Kaithi in his diary on 14 April 1917: “I have difficulty in speaking Hindi and neither do I know Bhojpuri, nor the Kaithi script, in which all the documents are.”

The letters of many indentured labourers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, sent to places like Mauritius, Trinidad, Suriname, and Fiji, were also written in Kaithi, Das said.

But Kaithi wasn’t just for the masses. India’s first President, Rajendra Prasad, wrote letters to his wife in the script, and famed Bhojpuri playwright Bhikhari Thakur used it for his works.

A second act for Kaithi

While the land survey has brought Kaithi back into the limelight, passionate advocates like Das have been quietly working to revive the script for years.

Since 2011, Das has organised over a dozen Kaithi workshops across Bihar, training over 1,500 people.

“I have been working on Kaithi for 15 years, but the land survey has really given it a boost. Finally, the government is paying attention to something we’ve been trying (to promote) for a long time,” he said.

For about a decade, Das has teamed up with museum curator Shiv Kumar Mishra to run workshops.

In 2022, they held a week-long workshop in Bhagalpur, which inspired the vice chancellor of Tilka Manjhi Bhagalpur University to introduce a six-month certificate course in Kaithi under the Maithili department last year.

The first batch comprised 22 students, while 40 people enrolled for the 2024 course in Tilka Manjhi, including PhD candidates from Jamia Millia Islamia and local newspaper editors. Pritam Kumar, who trains Bihar’s land surveyors in Kaithi, also teaches at the university, while his colleague Waquar Ahmad, is a student there.

Initially, the Land Department reached out to Mishra and Das to take the training classes, but they declined due to their own jobs and recommended Pritam Kumar and Ahmad instead.

Though Tilka Manjhi Bhagalpur University is currently the only institution in Bihar teaching Kaithi, plans to introduce similar courses at Munger and Patna universities have been in the works since 2020. Munger University has already prepared a syllabus, but the course has yet to begin.

Professor Ram Sevak Singh, head of the Maithili department at Tilka Manjhi, noted that the practical benefits of Kaithi are finally becoming apparent.

“Those who could read Kaithi have now grown old. So, it is necessary to nurture new people so that the disputes related to the script can be resolved,” he said.

Also Read: Urdu is the ticket to a govt job in this Rajasthan village. Even more than English

Bottleneck and backlash

The land survey has stirred up a hornet’s nest in Bihar, with collectorates, courts, and record rooms across the state clogged by people scrambling to prove land ownership. Kaithi translators are suddenly in high demand—and commanding hefty rates.

In the waterlogged and muddy premises of Samastipur district court, 54-year-old daily-wage labourer Premchand Chaudhary was searching high and low for a Kaithi translator to decipher the records for his 5 bighas of land. The papers had been lying forgotten in an old box, but when the survey started, he pulled them out—only to find he couldn’t read a word. But there are only two translators on the court premises, and neither had a minute to spare.

One translator was working from home when Chaudhary arrived, while the other, 58-year-old Indradev Prasad, told him to come back next month. Prasad has been translating Kaithi for the past 20 years and has never been this swamped.

“Earlier, Kaithi translations were needed only for court cases. But due to the survey, translations have increased a lot. I’m unable to meet the demand,” said a harried Prasad, clacking away at his typewriter.

With the spike in demand, the cost of translation has shot up.

“Kaithi translators used to charge Rs 200-300 per page. Now it’s Rs 1,000-1,500,” said Arvind Kumar, who runs a photocopy shop in the court premises.

In desperation, some people have turned to learning Kaithi online. YouTube tutorials are gaining traction, and interviews with translators are circulating on social media. But this hasn’t solved the backlog.

District archives are equally overwhelmed. Before the survey, an average of 400-500 applications for documents were received each week in districts. Now, that number has jumped to 2,500-3,000, according to a senior Land Department official.

The discontent has now become a political hot-button issue too. Opposition leaders accuse the government of bungling the survey and allowing corruption to fester in land offices. Pollster-turned-politician Prashant Kishor has coined the slogan “Triple S”—Sharab bandi (prohibition), survey, and smart metres— arguing that the land survey is the last nail in Nitish Kumar’s political career.

Meanwhile, Revenue and Land Reforms Minister Dilip Jaiswal has repeatedly reassured the public that there’s no need to panic. Late last month, the government also granted people a three-month window to arrange their documents. District magistrates have also been instructed to crack down on fraud, said the department’s secretary Jai Singh.

The government’s Kaithi training programme is now being seen as something of a silver bullet.

“Due to lack of knowledge about it, there is no clarity about the khatian (land records). Kaithi training will solve this problem to a great extent,” said Dinesh Kumar, settlement officer for Samastipur.

But experts like Bhairab Lal Das caution that Kaithi should not be seen merely as a tool for resolving land disputes.

“If people learn Kaithi only to read land documents, then it will be injustice to this script,” Das said. “If its cultural dimension is paid attention to, then many aspects of history will be revealed. Take any step into history, and you will find Kaithi there. When a script dies, a culture perishes.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)