Netarhat (Jharkhand): Deep in the forested hills of Latehar district, retired IAS and IRS officers often make a quiet detour—not to a government office, but to a school. The Netarhat Residential School is revered by its alumni and its badge of pride—the “Doon School of Bihar and Jharkhand”—is mentioned at weddings and village fairs. Established in 1954 as a free residential school for boys, it has produced over 500 civil servants, including more than 75 IAS and IPS officers.

Today, the school is just a shade of its former glory, remembered largely through the visits of its distinguished former students.

“Those who studied here see it as more than a school—it’s a heritage,” said principal Santosh Kumar, as he listed recent visitors: former Jharkhand chief secretary Sushil Kumar, former tax commissioner Shiv Sundar Bhagat, and DY Patil University vice-chancellor Prabhat Ranjan. “We make the most of these visits. It’s when people start talking about Netarhat again,” he added.

Once a premier gateway to the civil services, Netarhat shaped young minds not only through textbooks but through a culture of discipline, debate, and diligence. Alumni such as Amit Khare, an adviser to the Prime Minister’s Office, and Ajay Kumar Singh, former Jharkhand DGP, credit the school for building the foundation of their career with a rigorous routine and competitive atmosphere. They also praise the distance from urban distractions that helped them prepare for national-level exams.

There was a time when Netarhat Residential School, perched on top of the Chota Nagpur plateau, symbolised aspiration. Families across Bihar and Jharkhand dreamt of sending their children here. But over time, its reputation declined. The bifurcation of Bihar, the rise of private schools, and an absence of political vision slowly chipped away at its standing.

“Netarhat was once the pride of Bihar. After Jharkhand was carved out, it got lost in political reshuffling. The boom of private schools and a lack of will to modernise [meant] it slowly lost the attention it deserved,” said Santosh Oraon, an alumnus and retired bureaucrat who has tracked the school’s journey closely.

Everyone here feels the change—from students who wash their own dishes before class, to teachers using outdated tools, to alumni returning with a mix of pride and concern. The school is caught in a delicate moment—its prestige bruised, but its promise still intact.

Today, there is a renewed push to restore Netarhat to its former stature. Committees have been set up, problem areas identified, and inputs sought from students, teachers, and alumni. From bureaucrats in Ranchi to old boys in Delhi, the alumni network is being mobilised in full force.

But this isn’t the first revival effort. Around 15 years ago, an autonomous body was created to give the school greater administrative control. A seven-member committee, led by an alumnus, was empowered to make decisions on infrastructure, staffing, and governance. Yet the expected transformation never came.

“The school and its students never got the growth they deserved. There was no long-term political vision. It would help if the Centre steps in and develops Netarhat into a modern school,” said former Rajya Sabha MP Rakesh Sinha, also an alumnus.

The rot

For 33-year-old Chander Shekhar, the legacy of Netarhat Residential School casts a long shadow. A 2007 graduate, now Deputy Superintendent of Police in Jamtara, Shekhar recalls how his alma mater followed him through every chapter of his life—from Delhi University’s law faculty to the Delhi High Court and later, the police service.

“I come across senior alumni quite often. Every time we meet, it takes us back to childhood and the best years of our lives,” he said.

He can rattle off names of seniors who rose to become IPS officers, top lawyers, and forest service officials. But when it comes to juniors, Shekhar is left wondering.

“I know a few who went to FTII and are working in cinema. the school’s results have definitely been affected.”

The numbers tell the story. In the 1980s and 1990s, Netarhat received over 40,000 applications annually. Today, that number has fallen to just 2,500. Once a three-stage admission process modelled on the UPSC—with a preliminary test, main exam, and interview—the entrance is now reduced to a written test and interview for just 100 seats in Class 6. The pool has shrunk. So have expectations.

Many students still hear about Netarhat’s former stature, but that pride has worn thin. Today, private schools like DPS Ranchi, Jawahar Vidya Mandir, and Bishop Westcott have become the academic centre of attraction. These schools have smart classrooms, robotics labs, and English-medium instruction.

“My cousin goes to a private school in Ranchi. It’s very expensive, but he is exposed to robotic labs, smart boards, all of that,” said a Class 12 student, walking to his chemistry class. “We have a computer lab too, but our digital infrastructure can’t really compare with private schools.”

The difference is stark—and not just in facilities. Private school students routinely top the CBSE board exams. Netarhat, which once followed the Jharkhand state board and would have at least three-four students feature in the top 10, hasn’t made it to the merit lists since its shift to CBSE four years ago.

Teachers say they are still adjusting to the new board.

“It’s true we haven’t made it to the top ranks in CBSE results,” said Ravi Prakash, a faculty member. “Most of our students come from rural areas and need time to adapt to the new syllabus. Our teachers also have CBSE duties in other schools, which limits their time here.”

Even Shekhar, who holds the school close to his heart, admits it hasn’t kept pace.

“Nowadays, every city has multiple schools with good faculty, so parents don’t want to leave their children in a boarding school,” he said. “Still, a visit to Netarhat is always special.”

Work of revival

With its immaculate lawns that could give Delhi’s Lodhi Gardens a run for its money, sloping red-tiled hostel roofs called asharams, and bright, airy classrooms, Netarhat Residential School could be mistaken for an expensive boarding school in the hills of Shimla. But the whirr and whine of drills and clanking of machines break the campus calm.

Renovation work is in full swing. New science labs are under construction, classrooms are getting spruced up, and infrastructure upgrades are underway—all part of an urgent state-led effort to make Netarhat Residential School great again.

Over the past six months, the Jharkhand government has held multiple rounds of meetings with teachers, alumni, and education officials to map out a recovery plan. Among the issues flagged include infighting among staff, a corruption scandal in the school kitchen, lack of data transparency, and the absence of a clear political vision.

“I accept that the glory the school once had is no longer there. But we’ve made serious efforts. A high-level committee has been formed, and it’s looking into every issue. The report will be submitted within three months. The file is with the Chief Minister [Hemant Soren],” said Uma Shankar Singh, Jharkhand’s education secretary.

One incident that shook public trust involved a teacher caught accepting a Rs 50,000 bribe linked to kitchen operations, a sign that a culture of complacency had set in.

The committee is now pushing for a multi-pronged solution: transparent hiring of qualified teachers, academic reforms, infrastructure modernisation, and more government oversight.

“Groupism among teachers and internal conflicts diluted the school’s legacy,” he said. “There’s no shortage of budget. But there’s a lack of vision, and we’re going to work on that.”

Teachers at the school have requested tools that go beyond just books and blackboards—robotics labs, smart classrooms, and basic infrastructure for AI education. The goal is to expose students to modern tools like ChatGPT and other software that are available in elite private schools.

“There’s no problem in providing labs and tools, but the required skills [among staff] aren’t there. We are addressing these issues,” Singh said.

To boost admissions and revive interest in the school, district education officers have been instructed to conduct outreach in rural blocks. They are organising orientation sessions, distributing entrance forms, and guiding students through the application process. Newspaper ads have also been placed across Jharkhand to spread awareness and encourage more applicants.

“It’s true the results aren’t what they once were. But we’re working with the government to increase applications. Only then can we attract the best students again,” said the principal, who took charge last year.

Netarhat Residential School was set up under the supervision of British educationist Frederick Gordon Pearce. Regarded as the founder of the Indian public school movement, Pearce had earlier led educational reforms in Gwalior and served as principal of Rishi Valley School, believing Indian education needed a new kind of boarding school. In 1951, he laid out what became known as “Pearce’s Scheme”—a model that combined the rigour and discipline of British public schools with the simplicity, self-reliance, and moral education of India’s Gurukul tradition. Netarhat was the first state school built on that blueprint.

While that Gurukul-inspired ethos remains—the shared chores, the moral instruction, the spartan lifestyle—some parts of the original model have disappeared. Chief among them: English instruction.

“We do have English textbooks, but most teachers end up teaching in bilingual mode,” said teacher Ravi Prakash. “The students come from rural areas, and they’re not fluent.”

Until recently, an autonomous body managed key decisions at the school—from recruitment to overseeing infrastructure development to managing the administration. But it could not deliver the turnaround many had hoped for. While autonomy gave the school some breathing room, the efforts fizzled out in the abscess of a strategic direction and consistent government backing. That’s changing now.

“There has been no review system until now,” Singh said. “We are going to create space for that. This is a great school, and we have to preserve the glory that has faded in recent years.”

The present

Eleven-year-old Ankit Kumar from Hazaribagh wanted to become an IPS officer, but he didn’t know how to chase that dream. His parents couldn’t afford private school tuition or coaching classes. So he turned to YouTube and typed in a simple query: “To become IPS, which school in Jharkhand?” That’s how he discovered Netarhat Residential School.

It’s been barely a month since he enrolled, and every day still feels unfamiliar.

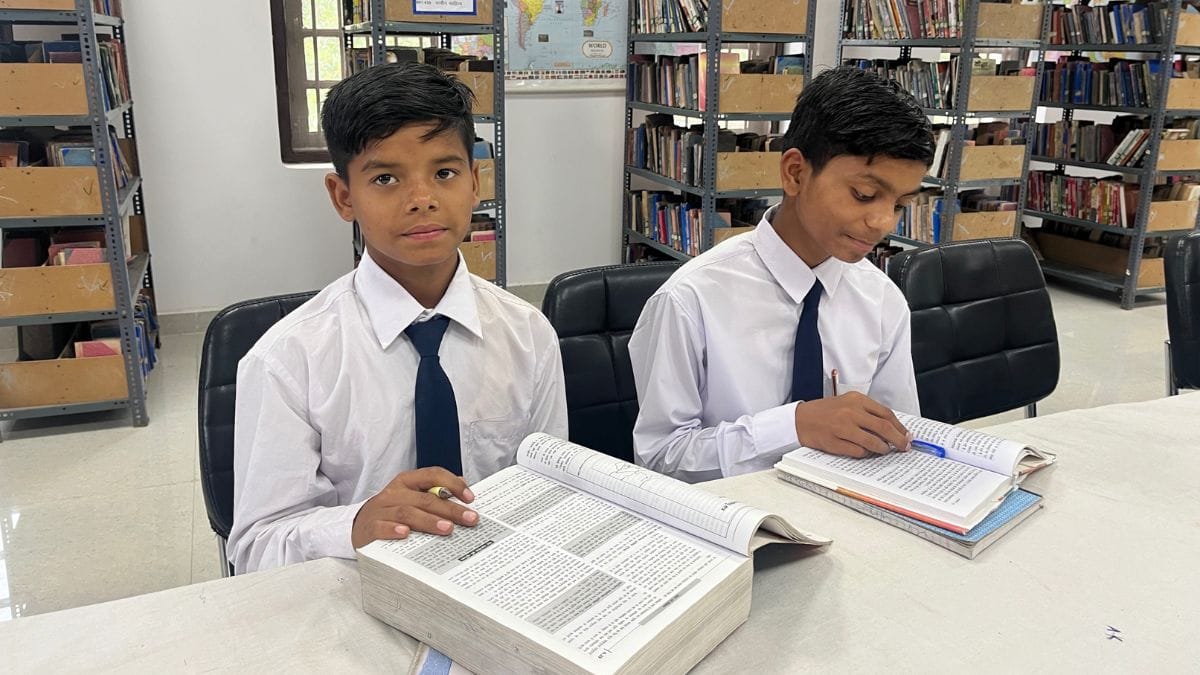

“The discipline here is very strict. We have to wake up at a certain time, wash dishes according to the roster. I’m adapting, but I think it’s good for my growth,” he said, scanning the shelves of the school library for something new to read. Nearby, his senior Vishal was buried in a Hindi fiction novel.

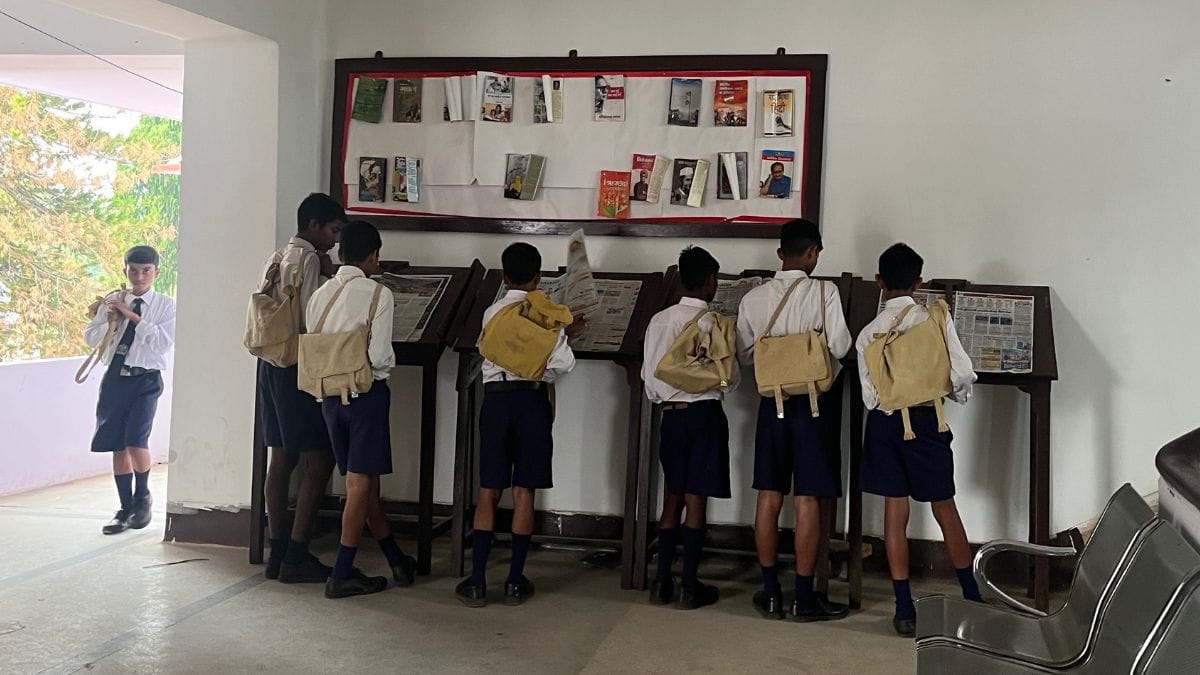

The library, with its wood-panelled glass shelves and soaring ceiling, exudes a quiet, old-world charm. Outside, newspapers are neatly arranged on a long table; students gather around them each morning to keep up with current affairs.

Between classes and daily chores, students often cluster in the gardens or sit under tall trees, poring over books. Every few hundred metres, clay pots have been placed around campus to provide cool drinking water.

Students address teachers in a manner that reflects the school’s Gurukul-style roots: “Namaste Shriman ji, Namaste Mata ji.” Unlike most schools, where teachers move between classes, here, each teacher is assigned a fixed classroom. It’s the students who rotate between rooms according to their timetable.

“We get only 10–15 minutes to switch, so we have to be quick,” said one student as he rushed off to political science class, where their teacher Mukesh Kumar was waiting.

That sense of structure and discipline is central to life at Netarhat. PT begins at 5:40 am, and every boy is expected to be on the ground in shorts—even in the biting cold of winter. Seniors mentor younger students and help them adjust to the rigours of residential life. Phones are not allowed. Students speak to their families only through the school’s landline, and family visits are rare. The school also runs its own health centre, and students are treated on campus unless seriously ill.

Most students here come from rural blocks of Jharkhand—the sons of farmers, government clerks, teachers, and small shopkeepers—united by the hope that Netarhat will transform their futures.

“This school is free. Intelligent students who clear the entrance test join. Most are from modest backgrounds, and a lot of time and effort goes into training them,” said the principal.

Students build bonds while performing their daily duties—washing utensils, sweeping corridors, tending to gardens. It’s part of the school’s ethos of shared responsibility.

“Initially, I was embarrassed to wash dishes used by others. But slowly it got better, as everyone has to do it when their turn comes,” said Mohit Kumar, a Class 8 student. He, like many of his classmates, is excited about the facelift the campus is getting.

New classrooms have been built, the walls freshly painted, and the gardens restored to their former glory. These changes have accelerated since the school’s governing structure became autonomous. Earlier, such decisions had to go through state government channels and were often delayed. Now, the school’s internal committee—chaired by alumnus Santosh Oraon—handles many of these approvals.

“Teachers used to wait for their salaries. Managing infrastructure over a 460-acre campus was difficult with government coordination. After the autonomy, things have improved—recruitment, infrastructure, everything,” said Oraon. He welcomed the government’s renewed interest in Netarhat’s future.

Back in the library, Ankit Kumar was quietly flipping through a book of poems by former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

“I know the last few years haven’t been good for the school,” he said, “but for kids like me, it’s still the gateway to our dream of becoming a civil servant. And if everyone is working to bring it back, we’ll do our part too.”

(Edited by Prashant)