New Delhi: Like many young, educated Indian men, the student of natural science in Cambridge wrestled with his future. Should he choose law, politics, or the “heaven-born” Indian Civil Service? He dropped this idea for practical reasons. It would have meant distant postings, and his parents wanted him close.

That student was Jawaharlal Nehru. Later, in his autobiography Toward Freedom, he recalled deciding against giving the ICS exam.

“There was a glamour about it still in those days,” he wrote. “It is curious that, in spite of my growing extremism in politics, I did not then view with any strong disfavour the idea of joining the Indian Civil Service and thus becoming a cog in the British Government’s administrative machine in India. Such an idea in later years would have been repellent to me.”

But others of his generation, and the one before, who gave the ICS exam, did not necessarily divorce themselves from the nationalist cause. One of them was Subhas Chandra Bose. He ranked fourth in the exam, completed training, and then within a year, in 1921, walked away— rejecting prestige and pay for revolution.

Before Independence, the Indian Civil Service was the empire’s “steel frame,” designed to serve the Crown. Yet many of its Indian entrants turned it into a site of resistance in their own ways.

Satyendranath Tagore was the first Indian to join the ICS in 1863. Even as an officer in Bombay Presidency, he encouraged reformist thought and wrote patriotic songs. Surendranath Banerjea, who entered the service in 1871, was dismissed during a posting in Sylhet and turned to politics, founding the Indian National Association and later presiding over the Congress. His friend Romesh Chunder Dutt retired early and wielded his pen, exposing colonial exploitation in The Economic History of India.

It is not as if everybody who joined the civil service became a British trotty. Especially in the 1930s and ’40s, many civil servants shifted their allegiance to the nationalist cause

-Aditya Mukherjee, historian

They showed that even the Raj’s toughest exam could not keep nationalism out. It’s part of a legacy the UPSC now carries into its centenary as an institution of democratic India.

“In times of national crisis, Indian civil servants have not remained immune to the demands of society. They have listened to their conscience and made personal sacrifices — whether it was during the freedom struggle, when many gave up promising careers to join the national cause, or in our own times, when civil servants have gone beyond the call of duty to respond to emergencies, as we witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said UPSC chairperson Ajay Kumar.

Also Read: A century of UPSC. A ‘colonial tool’ rewired by protests, committees, even scandal

Dissent within the steel frame

When the Indian Civil Service formally opened to Indians in 1855, it was made as difficult as possible to crack. Aspirants had to go all the way to England to write the exam, and the syllabus was loaded with Latin and Greek. For eight years, not even one Indian made it through.

Then came Satyendranath Tagore in 1863, followed several years later by Romesh Chunder Dutt. Both showed it was possible to stay in the ICS and still question its superstructure.

“Satyendranath Tagore’s entry into the ICS was more than a personal triumph; it symbolised the first Indian breach in the steel frame of the empire,” Aditya Mukherjee, author and history professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, told ThePrint.

The elder brother of Rabindranath Tagore and a student of Presidency College, Satyendranath cleared the exam in London and, after probation, was posted to the Bombay Presidency as magistrate and collector. That did not stop him from writing essays and patriotic songs such as the anthemic Mile Sabe Bharat Santan (All Sons of India Unite). It was said to have been sung at the Hindu Mela, a Calcutta cultural festival that tried to awaken nationalist sentiment among Bengalis. He also supported women’s emancipation, famously taking his sisters out in carriages and sending his wife to England so she could enjoy greater freedoms. His last post was that of a judge in Satara.

In 1886, Rabindranath dedicated his poetry collection Kari O Komal to Satyendranath, acknowledging the inspiration he drew from his brother’s life of duty and reform.

For many, Satyendranath’s career showed it was possible to work inside the colonial system and still advocate for social progress and keep sympathies with the people of India.

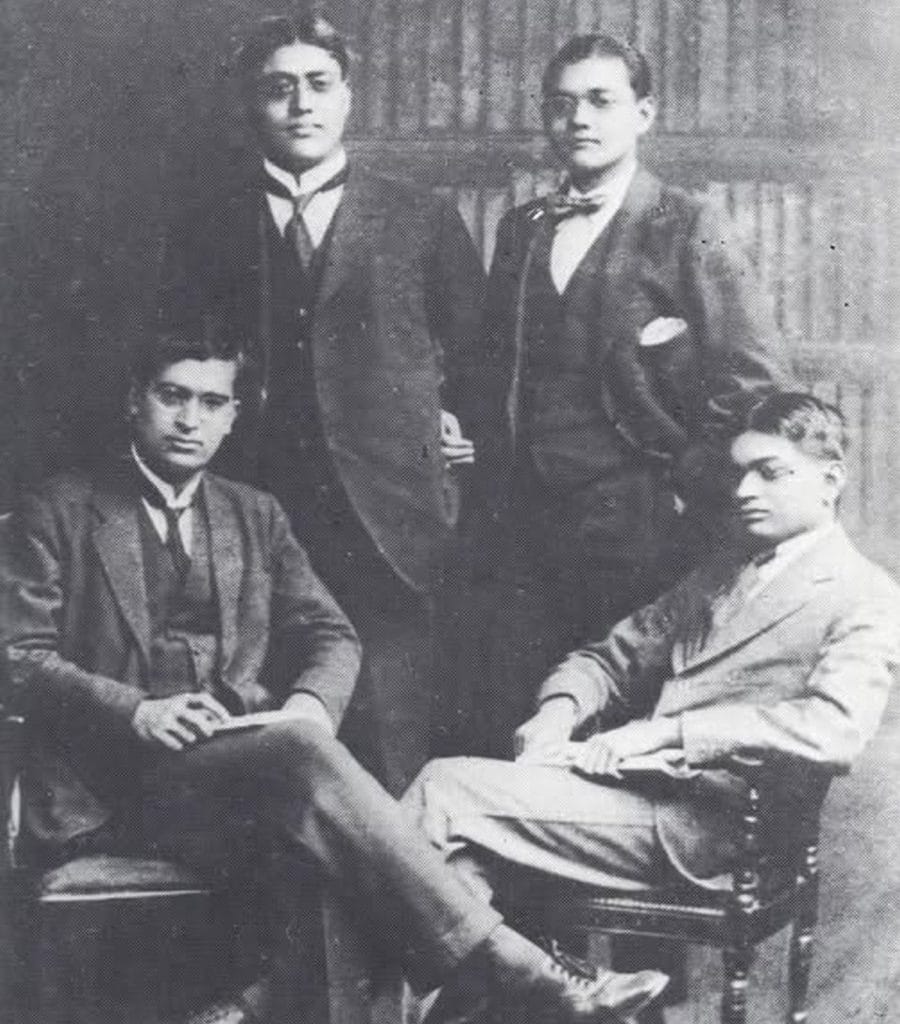

Several years later, another Presidency College alum, Romesh Chunder Dutt, passed the exam in 1869. So determined was he that he clandestinely went to England with two friends, without his parents’ approval. He joined University College and the Middle Temple, studying law, literature, and political economy, and after two years of preparation, ranked third. But he later critiqued the same system that had held so much allure for him.

As early as 1870, he wrote to his brother of two hopes: that India would adopt some “noble institutions” from Europe, and that his children would live to see the day when his country would “take her place among the nations of the earth in manufacturing industry and commercial enterprise, in representative institutions and real social advancement.”

For 26 years in Bengal Presidency, Dutt served as assistant magistrate, collector, settlement officer. In Burdwan, he became the “first native Commissioner in India” with Europeans under him, as the Anglo-Indian Journal put it. His work during the 1874 famine, and then the Great Backerganj Cyclone two years later, along with his advocacy for farmers, earned him a reputation for fairness and for balancing service to the government with service to the people.

I live to do my duty, and that inspires me with an exaltation to which rich men’s pleasures are nothing

-RC Dutt, in a letter to his brother

“I live to do my duty, and that inspires me with an exaltation to which rich men’s pleasures are nothing,” he once wrote to his brother.

Throughout, he wrote scholarly works such as Lays of Ancient India and The Peasantry of Bengal. His writings on British policies sometimes walked a thin line.

“Within the limits of the service, Dutt managed to write as a nationalist intellectual. When their work went beyond those limits, many officers had to resign. But his scholarship itself was a form of resistance,” said Mukherjee.

Dutt voluntarily retired early in 1897, after which he first worked as a lecturer at University College, London, and then returned home to serve as the president of the Indian National Congress in 1899. A few years later, in 1902, he wrote his seminal The Economic History of India, laying bare the British Raj’s economic exploitation.

“RC Dutt’s Economic History of India remains relevant even after a century. Like Dadabhai Naoroji, he exposed how British policies deepened poverty — preferring railways over irrigation, undermining Indian agriculture and industry, and draining India’s wealth,” said Mukherjee.

In The Indian Civil Service and the Nationalist Movement, historian BB Misra also wrote about how Dutt “carried into the service a keen sympathy for his countrymen” and then carried out of it “a lasting critique of the economic consequences” of colonial rule.

In the preface of his book, Dutt warned that unless there was a course correction, future historians might write of how the Empire gave India “peace but not prosperity” and about how manufacturers lost industries and farmers were ground down by heavy taxes.

He also quoted John Stuart Mill: “The Government of a people by itself… has a meaning and a reality, but such a thing as government of one people by another does not and cannot exist.”

A dream dismissed

A spirit of subversiveness was not uncommon among Indian ICS officers. By the 1930s and ’40s, some serving civil servants even tipped off nationalists about impending crackdowns.

“It is not as if everybody who joined the civil service became a British trotty. Especially in the 1930s and ’40s, many civil servants shifted their allegiance to the nationalist cause. Some even warned leaders during 1942 (Quit India Movement) that they were about to be arrested,” said Mukherjee.

But some who started out as ICS officers became towering nationalist leaders in their own right.

One of the two friends who travelled to England with RC Dutt to give the exam was Surendranath Banerjea, the only one with permission from his family. He too cleared the exam in 1869 but his entry to the service was delayed due to a dispute over his age.

I felt that my dismissal was a relief. It was indeed a crushing, staggering blow, but it meant absolution from a strain upon body and mind which had wellnigh become intolerable

-Surendranath Banerjea in his autobiography

He finally made it in 1871 but was dismissed three years later, officially for delaying a judicial order. In his 1925 autobiography, A Nation in Making, he blamed racial discrimination and jealousy, ruing that “my success was the cause of my official ruin.”

But at the same time, he claimed to have felt freed of a burden: “I felt that my dismissal was a relief. It was indeed a crushing, staggering blow, but it meant absolution from a strain upon body and mind which had wellnigh become intolerable.”

A career as an English professor ensued but he also threw himself into nationalism, founding the Indian National Association and taking over a newspaper called the Bengalee, where he published opinions that even got him arrested. Long before India had a Vishwa Guru, he was known as Rashtra Guru, The Indian National Association merged with the Congress and he was its president twice. His efforts are widely credited with playing a major role in the decision of the British to reverse the 1905 bifurcation of Bengal in 1912.

But if Banerjea was pushed out of the ICS, Subhas Chandra Bose chose to exit. He’d never wanted to join it in the first place.

Also Read: Ashok Khemka, whistleblower IAS officer transferred 57 times in 33 yrs, retires from service

‘Not an easy example to follow’

It was pressure from his Westernised family that compelled Subhas Chandra Bose to sit for the ICS exam in 1920. He wanted to study further in the University of Cambridge, but his father set a condition: he could go only if he prepared seriously for the exam. Bose agreed, and with just eight months of study cleared it in his first attempt.

“He had barely eight months to prepare for the ICS while also studying for his course exams. In the Sanskrit paper, he even lost marks because he couldn’t copy his translation into the answer sheet. Yet, such was his natural ability that he cleared the exam in his first attempt, securing the fourth rank. He might have ranked even higher otherwise,” said Chandrachur Ghose, historian and author of Bose: The Untold Story of an Inconvenient Nationalist.

[Bose] confided in his elder brother but didn’t have the courage to tell his parents, who wanted him to join what was then called the ‘heaven-born service

-Chandrachur Ghose, historian

This success left him cold. Even before the results were declared, he had made up his mind not to serve a foreign government, according to Ghose.

“He confided in his elder brother but didn’t have the courage to tell his parents, who wanted him to join what was then called the ‘heaven-born service’,” he added.

For a while, Bose was swept along by the tide of expectations. He served his probation but could wait no longer. He wrote to his elder brother and informed him about his decision to quit the ICS in 1921.

“Bose only served his probation before resigning, but even that act became an extraordinary example of sacrifice and courage. He may not have had Gandhi’s or Nehru’s winning strategy, but he created a legacy of heroism,” said Mukherjee.

Bose did not resign from the ICS on an impulse; it was a deliberate choice to enter public life on his own terms. He’d already been in touch with nationalist leaders.

“He wrote to Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das, sharing his ideas about reorganising the Congress and asking how an educated man like him could contribute to the movement,” added Ghose. The young probationer who walked away would go on to be known as Netaji, the leader who raised the Indian National Army against the Raj.

For an Indian to give up the ICS voluntarily was unheard of at the time. His resignation became a talking point among students at Oxford and Cambridge. The debate, according to Ghose, centred on whether the ICS was a worthy goal at all, and if officers were anything more than “high-powered clerks” carrying out the orders of their British masters. Yet, few others followed that example.

“Only Hari Vishnu Kamath, much later in 1937, resigned from the ICS to join the national movement,” Ghose said. “Subhas set an example, but it was not easy to follow.”

This is the third article in ThePrint series UPSC@100.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

To add to the headline, India made it ‘Indian socialist service’.