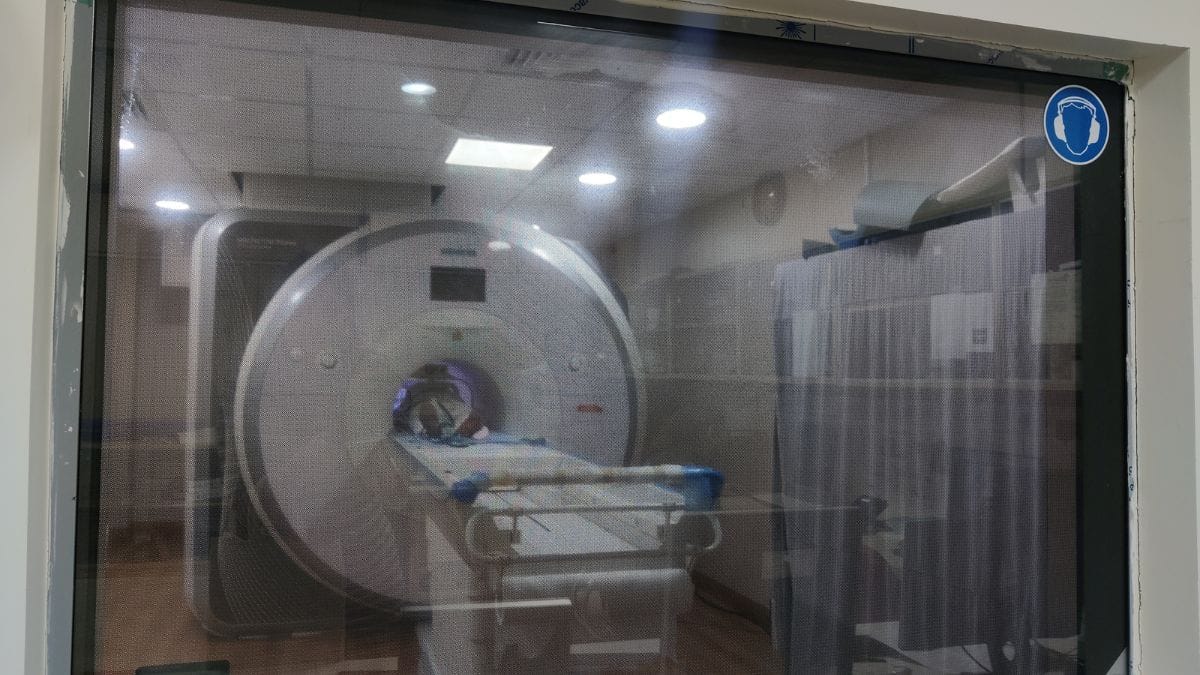

Manesar: When the bed slides into the MRI machine, Patient 321—a 65-year-old woman from a Haryana village—hears the tunes of a Krishna bhajan. At the National Brain Research Centre in Manesar, this music is supposed to help calm her for the 45-minute-long examination. This isn’t a routine medical checkup, after all—she’s one of the thousands of participants in India’s largest-ever project to understand how dementia works and spreads.

Over the last year, every week, people aged between 60 and 90 from Palwal district in Haryana come to the National Brain Research Centre (NBRC) to get their brains scanned. They’re provided with patient IDs to protect their anonymity. A few of them have been diagnosed with either dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and are accompanied by their caregivers and family members. The NBRC, India’s only institute dedicated solely to neurosciences, is coordinating with three institutes based in three different cities—Bengaluru, Kolkata, and Delhi-NCR—for a national-level dementia study.

Located in a secluded campus off NH-8 in Manesar, the 28-year-old NBRC is unique both in its structure and function. It offers both research and education, and has one of the country’s few MSc programmes in neurosciences. It has a faculty of 15 professors, who each lead their own research group. Founded by the Union Ministry of Science and Technology, the institute has always had a national interest bent.

“We are looking at how North India’s rural population is ageing, and how dementia sets in,” said Dr Arpan Banerjee, the Principal Investigator at NBRC who leads the National Dementia Science Programme. “We’re trying to understand how dementia affects the brain’s structures and functions.”

While the latest estimates suggest that over 88 lakh Indians suffer from dementia, there has never been a nationwide study to determine how the neurodegenerative disease affects them. By 2050, one study predicts, over 1.1 crore Indians will be dementia patients. Global research has established the role of culture and context in dementia, but scientists are still unaware of how it works in the Indian context.

Yes, we are creating a database of dementia MRI scans in India, but we’re also doing fundamental research that we hope will translate into clinical practices. Whatever work we do here, we want it to be geared toward a majority of Indians, who are majorly non-English speakers from a rural background, just like our cohort.

Dr Arpan Banerjee, Principal Investigator, NBRC

The NBRC study stands to change not just Indian but global dementia research, contributing data from a hitherto unknown cohort—rural, monolingual, non-English speaking, and largely illiterate people from North India.

“The significance of this research is very simple—as we live longer, we’re going to be burdened with typical old-age disorders, of which dementia is the most common,” said Banerjee. “It will bring a cost to society in terms of providing healthcare and other needs to dementia patients, and it’s better to establish our own research rather than rely on the West.”

NBRC’s dementia brain scanning project

Among other things, the sprawling NBRC campus is host to a state-of-the-art MRI machine and a circular building for the senior faculty with arches on the outside that students think is modelled after the brain.

On Mondays and Wednesdays, Dr Banerjee’s PhD students await the arrival of the cars from Palwal that bring the participants for the dementia scans. Manesar’s NBRC seems like a different world to the Palwal residents. As it goes, some of the most characteristic symptoms of dementia include confusion, memory loss, and even loss of speech, so the PhD students have to be extra careful in handling the patients for the study.

“With many people, it’s the first time they are seeing an MRI machine, so it is naturally quite daunting,” said Vinsea Singh, a fifth-year PhD student who assists with the project. “But we do everything possible to put them at ease before the procedure.”

The INCLEN Trust, an NGO that works at the grassroots, selects a group for the study every week. Since INCLEN has a presence in many parts of India, the NBRC decided to partner with the foundation to access participants for the study.

We take as holistic a picture of the brain as we can get. And we take the same scans for healthy patients, patients with mild cognitive decline, and patients with dementia, so we can compare and contrast.

Vinsea Singh, PhD student

INCLEN’s own methodology includes administering a neuropsychological test to ascertain whether the participants have dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or no cognitive impairment at all. Their associates also travel with the participants weekly to NBRC and assist the patients suffering from dementia.

On the chilly ground floor of the MRI Building inside the NBRC campus is the room with the Siemens Prisma MRI machine that greets the participants. A small room to the side leads into a seating area, complete with a TV, where the students play an informational video for all participants when they come in. There are even blankets in case some people get cold, since the machine demands a certain AC temperature to function.

“We tell them exactly how the process will take place—the video says what the machine looks like, how long they’ll be inside for, what they’ll see and hear, and what they have to do while they are being scanned,” said Singh. “It allays most fears, and we assure their caretakers that we will be present in case they need anything in the middle.”

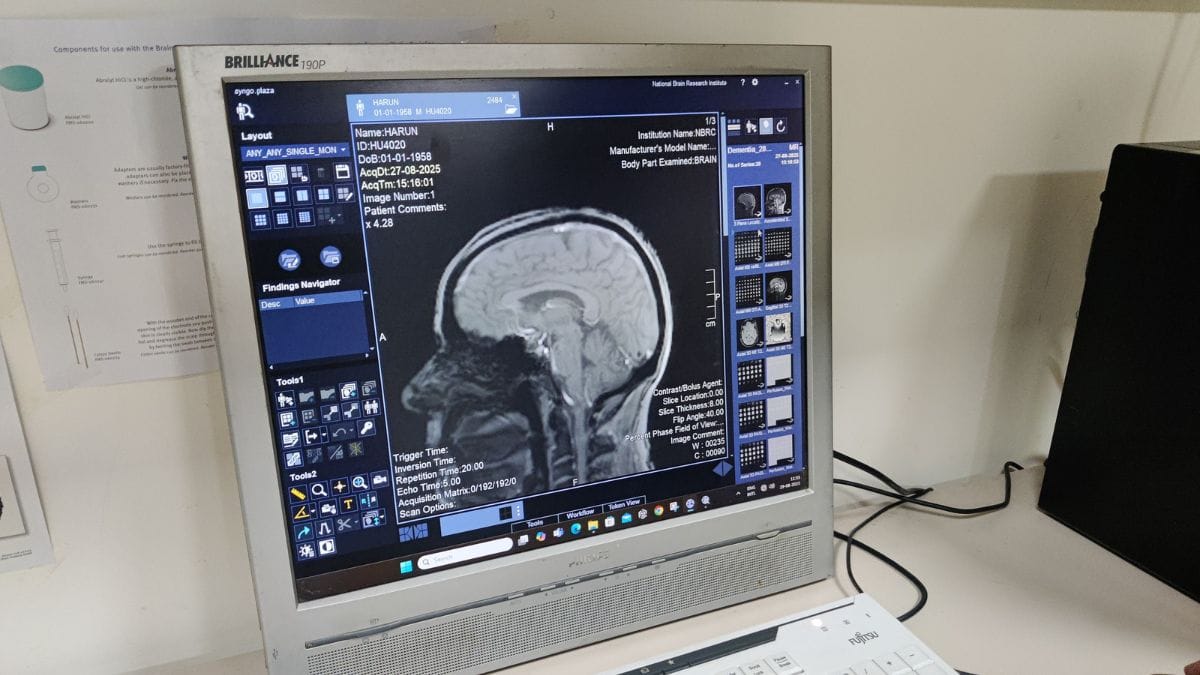

After being briefed, willing participants sign a consent form and are led into the MRI room. Alongside the standard structural MRI, which merely looks at the structure of the brain and takes high-resolution images, the dementia patients also go through a functional MRI, which measures their brain’s activity in different segments.

“We take as holistic a picture of the brain as we can get. And we take the same scans for healthy patients, patients with mild cognitive decline, and patients with dementia, so we can compare and contrast,” said Singh.

“The most common form of dementia globally is Alzheimer’s dementia, but it’s not the only one. There are others, like dementia caused by strokes, or by Parkinson’s, or Lewy bodies disease,” explained Prateek, a second-year PhD student under Banerjee.

The structural MRI gives detailed images of every part of the brain on a section-by-section basis. The cerebral cortex, the white matter, the cerebellum, and even the ventricles, which sometimes enlarge during dementia, are clearly visible through this MRI. A functional MRI, on the other hand, requires the patient to focus on one task—in this case, just a small black dot on a screen—so that the machine can monitor how oxygen flows within the brain when it is active.

“We’ll start analysing the scans soon, but since there’s no precedent of a study like this for dementia patients in India before, we’re basically going into this blind,” Singh said.

Also read: Belagavi to Boeing. Karnataka aerospace hub is a shining postcard for Make in India

A unique cohort

While they are part of the larger brain scanning project for dementia across India, the participants of the NBRC study stand to make a unique contribution to dementia research worldwide. It has to do with a seminal paper from 2013 by Indian scientists, which claimed that being bilingual can delay the onset of dementia by at least four years.

The paper was the first time in India that a connection was made between language learning, neural networks in the brain, and dementia. It also went on to cement how cultural and social differences could impact the onset of the disease.

Most of the participants from Palwal are rural, speak only one language, and quite a few of them are also illiterate, having never received a formal education. These factors make them stand out in comparison to those from Kolkata and Bengaluru, but also from other global subjects of dementia studies.

“We have the unique opportunity to see whether [the participants] being monolingual and Indian reverses the 2013 paper’s hypothesis,” said Banerjee. “Will it, for instance, lead to earlier onset of dementia? We don’t know; no one does.”

But Banerjee and his team of neuroscientists are trying to find the answer. The implications are clear, and neurologists across the country are watching in anticipation.

The data is all being stored together, to be analysed by Banerjee and his team once a substantial number of the 6,000 scans are collected. While the current phase of the project ends in December 2025, Banerjee hopes that DBT will continue their funding for at least the next three to four years so that they’re able to collect more scans.

“It is great that NBRC is doing this research, because it is much needed for India. All we have to rely on are scans from Western populations for dementia,” said Sinjan Ghosh, a cognitive and behavioural neurologist at Narayana Health. “Having an Indian dataset will help physicians so much.”

Banerjee, too, recognises the significance of the work for future clinical practices for dementia in the country.

“Yes, we are creating a database of dementia MRI scans in India, but we’re also doing fundamental research that we hope will translate into clinical practices. Whatever work we do here, we want it to be geared toward a majority of Indians, who are majorly non-English speakers from a rural background, just like our cohort,” Banerjee added.

According to the World Health Organisation, over 57 million people were suffering from dementia worldwide in 2021. Most of these live in low-income countries, and women seem to be affected more than men. A paper published by CSIR-NIScPR in 2023 called for a “national plan” to tackle rising dementia cases in India and highlighted the need to combat the stigma associated with the disorder.

“It is a fact that even in 2025, dementia cases are very underreported in India. Most people think that this forgetfulness is just a normal part of ageing, but that’s not true. The project in NBRC could be so helpful for primary healthcare physicians to recognise signs of dementia early on,” Ghosh said.

Banerjee’s students, who interact with the patients on a daily basis, sometimes see the behavioural effects.

“We often notice that the dementia patients who come for the project have to be handled by their caretakers, almost like children,” said Tanmay Singhal, another PhD student under Banerjee. “They need to be explained things gently and repeatedly, and they ask quite a few questions too.”

While dementia is the final stage where cognitive functions are completely hindered, the earlier stages are called mild cognitive impairment or MCI. These are fundamental to understanding how dementia spreads, and where.

“Dementia doesn’t happen just like you wake up and suddenly are diagnosed. It’s a process that could impact anyone, and it has signs that are visible if you know where to look,” said Banerjee. “That is why, in Palwal, we’re also scanning the brains of people with MCI, so that we have evidence of how dementia progresses.”

Also read: Policemen suspended after Paneer goes bad in greater Noida. A tale of a protest & BJP leader

How the NBRC project could help

At the end of the 45-minute-long MRI scan, Patient 321 is helped back up by her caregiver and one of Banerjee’s PhD students. She had been instructed about a buzzer to press in case of difficulty during the procedure, but she didn’t need to use it. After she was escorted out to the seating room, Prateek and Singh began collating the information from her brain scans.

The data is all being stored together, to be analysed by Banerjee and his team once a substantial number of the 6,000 scans are collected. While the current phase of the project ends in December 2025, Banerjee hopes that DBT will continue their funding for at least the next three to four years so that they’re able to collect more scans.

“Places like the UK Biobank have 10,000 brain scans of dementia patients. If we’re to look proportionately, India has 1.3 billion [130 crore] people, so we would need at least 6,000 scans from each of the three cohorts to get a good sample size,” said Banerjee.

Although she works on multi-sensory perception for her PhD thesis, Singh has spent quite a lot of her time on the dementia study, which has taught her a lot. And she is excited to find out what the results would be.

“Just recently, I was reading a study that said that the tau protein, which causes Alzheimer’s—that most people believe begins in the brain—actually begins in the gut… There aren’t any clear answers yet, but so much research is showing us the complex interplay between genetics, diet, and culture in the onset of disorders,” she said.

Data from the US-based Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) shows that dementia onset in Latin American groups differs from that in the US, Banerjee said. This is primarily because the educational levels in Latin American cohorts were at a significantly lower level compared to their counterparts in the US. Multiple global institutes like the National Institute on Ageing in the US, UK Biobank, and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden are working on understanding the patterns of dementia in different cultures.

At this moment, NBRC’s research is adding to a global repository at the right time.

“We are striking the iron right when it’s hot—instead of catching up, we’re at par with global dementia research,” said Singh.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)