New Delhi: Babar Afzal was many things before he became an artisan — a professional hacker, an IIT Delhi guest innovation professor, a McKinsey globetrotter. But the tragedy of starving Pashmina goats in Kashmir changed the 49-year-old’s life. He went to travel with nomadic shepherds in the Valley and discovered art along the way. It all came together in his woolcraft startup, the Pashmina Goat Project. And its new home, befittingly, is the Kunj, a mall that’s trying to give Indian handicrafts a brand-new identity.

“A shawl that takes seven years to complete deserves recognition comparable to a 20-minute handmade luxury bag selling for $25,000. Indian craft has the power to redefine global luxury,” said Afzal, whose shop at the Vasant Kunj mall includes portraits of designers such as Yves Saint Laurent, Dolce & Gabbana, and Karl Lagerfeld crafted entirely from Pashmina goat hair.

The Kunj is the Modi government’s riposte of sorts to the Nehru-era Central Cottage Industries Emporium. As India’s first mall dedicated entirely to handicrafts and handlooms, it has more in common with the swanky DLF Emporio nearby than its beleaguered Janpath sibling, where figurines and carpets gather dust and employees go months without pay. The new mall frames India’s artistry not as struggling and socialist but luxurious and aspirational.

With its glass-front shops, escalators, tasteful lighting, artfully draped handlooms, and events such as ‘heritage weeks’ and curatorial walkthroughs, it doesn’t come across as a typical brainchild of the Office of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) under the Union Ministry of Textiles. Inaugurated in August, prominent visitors such as filmmaker Mira Nair and British High Commissioner Lindy Cameron have walked through its doors. Even Lakme Fashion Week kicked off here in October.

The mall is owned by the government, but the shops are leased to private brands and startups that work with artisans and pay them directly. A private-public partnership model is also in play.

“In our expansion, we’ve tendered for the selection of a PPP operator. Once selected, the handover will begin. This model doesn’t exist anywhere else—it will be unique to Kunj,” said Pradeep Yadav, assistant director of The Kunj.

It’s a very different setup from the Cottage Emporium, where a government corporation still controls virtually every aspect. It is redefining art and, through it, positioning India as a force in the world of high-end brands.

Prada’s ‘Kolhapuri-inspired’ sandals were much-talked-about, but assertiveness among handloom and crafts brands has been a growing trend for long. So far, the Kunj has 20 brands, including Khol Khel for handcrafted games such as chaturanga, P-TAL for brassware, Vimor for saris, and Boriya Basta for bags, and even two outlets of the Cottage Emporium, apart from exhibitions and festivals.

“The artist in India is always positioned as poor, struggling, secondary. But artisans deserve to be millionaires. Our products are often sold by others at massive markups, while the creators themselves earn a few thousand rupees. Closing that gap is my goal,” said Afzal.

Also Read: Crisis in Cottage Emporium—Rs 202 crore in dues, unpaid staff on silent protest, no AC

Craft in motion

If traditional malls have PVRs and arcade games, The Kunj has artisans conjuring up traditional Indian arts out of clay, brass, paper, and paint.

One section of The Kunj, known as the Craft Demonstration Program, is dedicated entirely to artisans who do their nimble-fingered work right in front of visitors.

On a busy weekend in November, Hadibandhu Behera took a lump of clay and let his fingers delicately dance with it. Little by little, the shape of an animal appeared. A child stared at him as if Behera were doing a magic trick. Once the form dried, he wrapped thin strands of brass around it, heated the structure with a blowtorch, and removed the clay from inside. A brass elephant stood on the table.

“The more detailed the design, the better the piece,” he said, lifting a finished figure.

This is the famous Dhokra art, the metal-casting technique Behera inherited from his ancestors. He has spent 15 years mastering the craft, practised in West Bengal, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Madhya Pradesh. His skill has earned him both state and national awards, and his parents and sister are accomplished artisans as well.

To reach a higher-end audience, the presentation must match their expectations

-Pradeep Yadav, assistant director of The Kunj

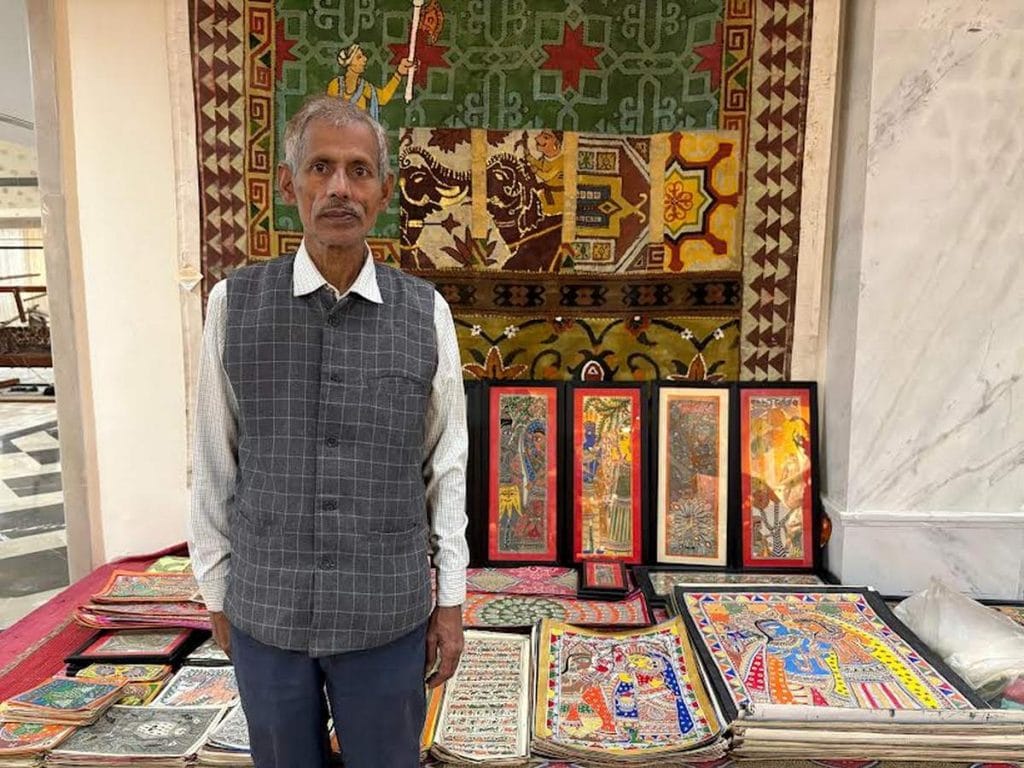

A few steps away sat Ganesh Paswan from Madhubani, Bihar.

He has been making Madhubani art since he was 14. Paswan learnt the art from his mother, just as his elder brother did. He supplied his paintings to the Cottage Emporium until 2013, and some of his work is also on display at Delhi Haat in INA.

“In the old days, we painted on walls coated with cow dung before festivals. Later, those same motifs moved onto handmade paper, opening the way to markets far beyond Madhubani,” said Paswan, whose family has earned state and national recognition.

The artisans are invited by the Ministry of Textiles, with the government covering their travel and accommodation. They don’t get a salary, but any income from sales goes directly to them.

New life for old crafts

Three chessboards — one carved from bone, one wooden, and one inlaid with tiny pearls — take pride of place on a table at Khol Khel, a shop at The Kunj devoted to India’s old strategy games. Standing beside them, owner Neetu Sureka talked visitors through each set, describing the materials used and the artisans who brought them to life.

She runs the shop with her husband, Aman Gopal Sureka, and their daughter Vidula. The family has spent nearly 15 years trying to revive shatranj, the older form of chess that was popular in the time of the Nawab of Bengal. In the pre-independence era, artisans carved remarkable sets from camel bone, sandalwood, stone, and silver, often collaborating with jewellers and miniature painters.

The brand’s collection includes more than 100 chess sets, crafted in 50 traditional Indian materials and styles. The family has also resurrected Buddhi-Yog and Buddhi-Bal, games that existed long before chess or Ludo.

“Many of the games you see here belong to ancient families of strategy—predator-prey formats, sacrifice-and-kill games, and regional versions of three-in-a-row. We also revive Chokobara, believed to be the ancestor of Ludo. Its movement style and gameplay show just how sophisticated our indigenous play systems once were,” said Neetu.

Both Neetu and Aman were computer professionals who started exploring game-based learning when their children were young. Aman researched how games could develop cognitive skills, strategic thinking, teamwork, and self-realisation. Khol Khel was incorporated as a private limited company in 2021 after the success of their ‘qboid’ playing platform, which won Toycathon 2021 in the ‘Social Values’ category, though formal operations began only in 2024.

The artist in India is always positioned as poor, struggling, secondary. But artisans deserve to be millionaires. Our products are often sold by others at massive markups, while the creators themselves earn a few thousand rupees

-Babar Afzal, founder of Pashmina Goat Project

The brand does not mass-produce its pieces, focusing instead on the artistry behind each set, with hand-carved wooden sets from Jodhpur, silver and Meenakari sets from Jaipur, jali-work in sandalwood and ebony from Jaipur, camel-bone pieces from Udaipur, and Dhokra metalwork pieces. The project is supported by the Ministry of Education, the Indian Knowledge System and the Ministry of Culture.

Handcrafted chess sets are priced in two ranges: Rs 5,000 to Rs 50,000 for contemporary designs, and a premium range from Rs 1 lakh to Rs 10 lakh, created by master artisans. The Kunj houses Khol Khel’s first physical store.

Nearby is another revival project: P-TAL, short for the Punjab Thathera Art Legacy. The Amritsar-born brand is revitalising the hand-hammered brass and copper craft of the Thathera community of Jandiala Guru, India’s only UNESCO-listed metalcraft.

What began as a college project at SRCC in 2016-17 under founders Aditya Agrawal, Kirti Goel, and Gaurav Garg rests on a nostalgic premise — bring back pure brass, copper, and kansa just as they were traditionally used, and let thoughtful design make them relevant for the modern kitchen. A recent appearance on Shark Tank India Season 3 gave the brand a wider audience.

Their range follows the traditional system of Indian households: brass vessels for cooking, copper for storing and drinking water, and kansa for eating. Prices range from around Rs 1,800 for a ghee pot to over Rs 3,500 for a brass thali set.

Also Read: Massage is the new career frontier for India’s blind

Where two worlds meet

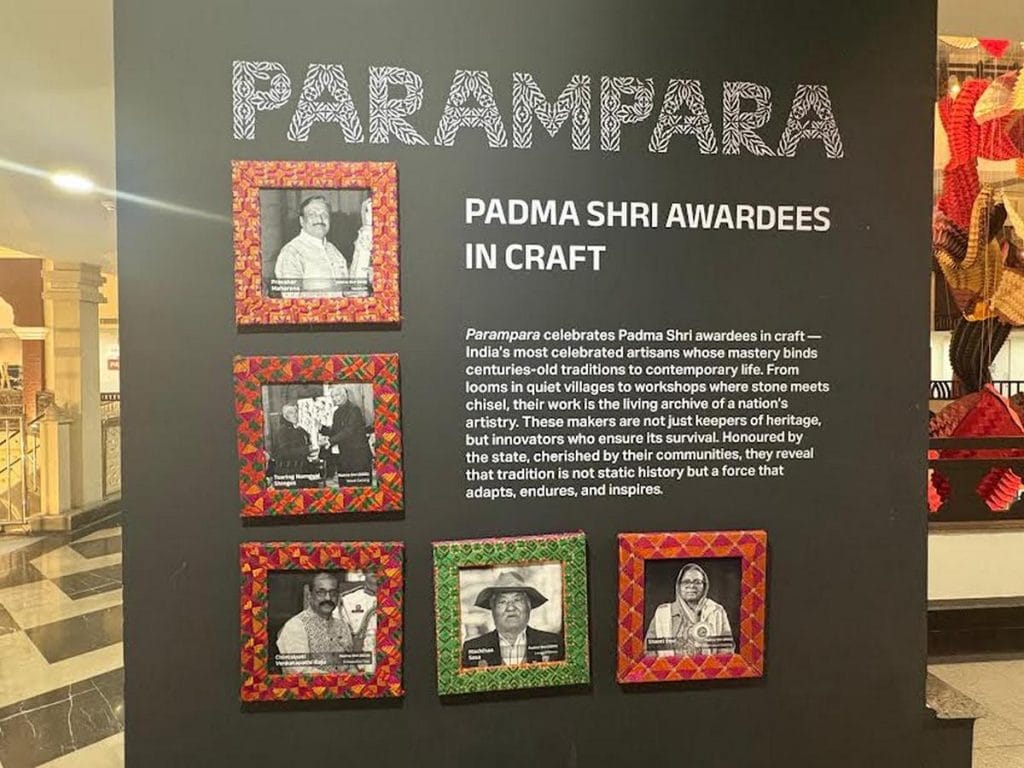

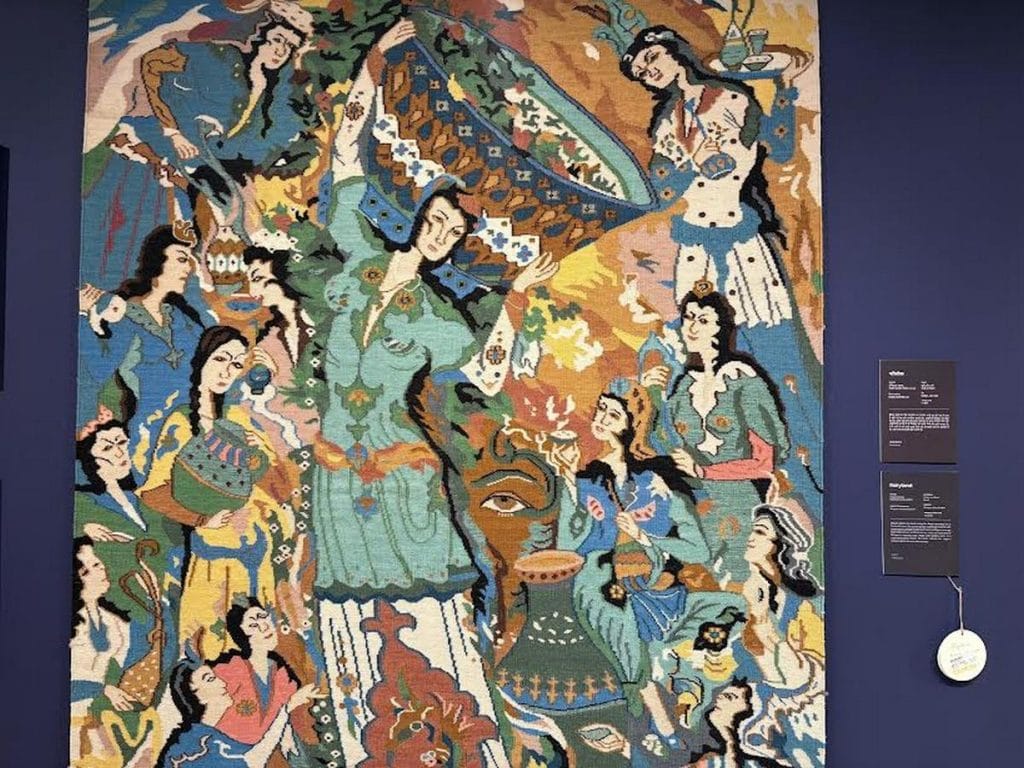

One corner of The Kunj looks less like a mall and more like a gallery. Each piece is displayed as if it were in a curated exhibition. Photographers wander through this section, capturing the finer details of the craftsmanship.

A tarkashi jewellery box from Mainpuri, Uttar Pradesh, is priced at Rs 1,05,000. A ‘Nature vs Human’ painting on Bengal handloom silk costs Rs 1,15,500. At the top end, a Lord Balaji sandalwood statue goes for Rs 18,00,000.

This presentation is geared toward enticing high-end clients, according to mall assistant director Yadav.

“To reach a higher-end audience, the presentation must match their expectations,” he said, adding that artisans receive direct compensation for the pieces here.

“This space is created exclusively for the artisans. We’ve set up this large exhibition ground to showcase their world-class pieces, and the payment goes directly to them. There’s no retail brand in between. The work belongs to the creators, not to us. We only curated the space,” said Yadav, who is the brain behind this section. He added that The Kunj gives artisans freedom to experiment in design, diversification, even market research, without having to bear the risks alone.

Today, Cottage Emporium has lost its charm—fewer products are on display, and many artisans are reluctant to provide their work. I’m not sure how long The Kunj will endure, but it can never be what Cottage is, or was

-an artisan, requesting anonymity

The past, however, still occupies a sliver of this shiny new world. The mall is home to two outlets of the Central Cottage Industries Emporium, one selling intricate handmade furniture, the other cutlery.

Back in Janpath, workers acknowledge that The Kunj is now absorbing many of the footfalls they’d normally get. Even as the mall displays well-known artists and high-end art, the Cottage Emporium artisans and staff are still awaiting unpaid dues. Yet, some still have a sense of pride and attachment.

“Today, Cottage Emporium has lost its charm—fewer products are on display, and many artisans are reluctant to provide their work. I’m not sure how long The Kunj will endure, but it can never be what Cottage is, or was,” said an artisan, asking to remain anonymous.

Another staffer said he hadn’t received his salary in months and is continuing with a ‘silent’ protest. But even for him, The Kunj cannot equal the inclusive Indian ethos behind the emporium.

“At the Cottage, each state has a separate space for its art, but here, there are brands,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Indian products are largely unaffordable to the masses. The problem continues right from M K Gandhi’s era. Our products must be accessible and affordable to the common man in the street.