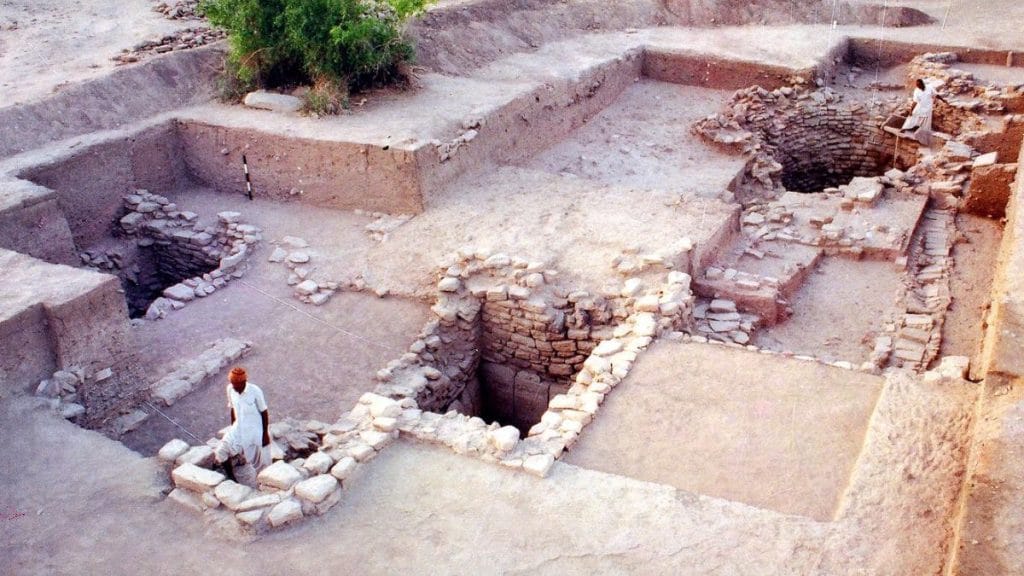

Rakhigarhi: The team of archaeologists teamed up with village labourers and pulled out several fistfuls of silt from a 10×10 trench a few weeks ago. Their eyes widened and they let out a collective gasp. With trembling mud-streaked hands, they brushed away centuries of mud.

They had long suspected that there was a Harappan-era water storage system at the dig site in Haryana’s Rakhigarhi. But their discovery that day exceeded all expectations—a mammoth reservoir, second only to the one at Dholavira in Gujarat.

It was nothing short of a marvel of engineering. Rakhigarhi, one of the largest urban centres of the Harappan civilisation, which flourished between 2600 and 1900 BCE, spans 500 hectares—nearly twice the size of Mohenjodaro. Yet nothing of this scale has been uncovered here. The December 2024 excavation laid bare an intricate and sophisticated water management system. Until now, wells had been found in Mohenjadaro and Harappa.

“Rakhigarhi was excavated many times, but no information about a reservoir was found until now,” said Sanjay Manjul, joint director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and excavation director at Rakhigarhi. “For the first time, a water storage area with a depth of about 3.5 to 4 feet has been revealed at Mound 3. The findings will help in understanding water management during the mature and late Harappan periods when rivers began drying, and people started storing water.”

These findings will give us an idea of the pattern of water management and how a society used to think

– Sanjay Manjul, ASI joint director general and excavation director at Rakhigarhi

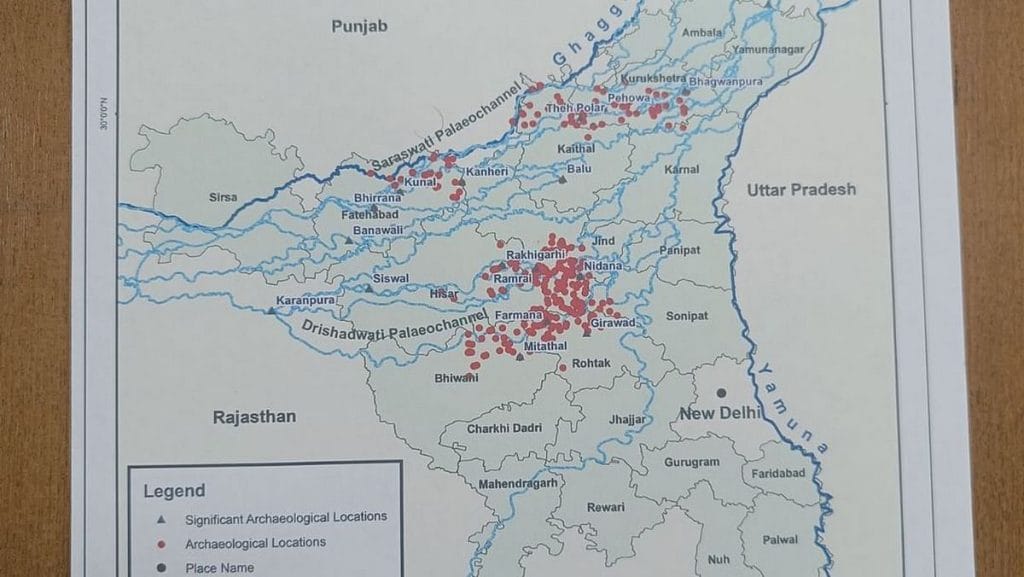

The reservoir also advances evolving research on the River Saraswati among geologists and archaeologists. During the mature and late Harappan periods, the Drishadvati River (also known as the Chautang River), the main channel of the Saraswati, started to dry around 3000 BCE. The reservoir was likely a response to the thinning river. Remote sensing data confirms the presence of paleochannels from the dried Drishadvati just 400 metres from the Rakhigarhi dig.

Over the past two decades, archaeological discoveries have been consistently confirming the idea of a mighty Saraswati River, mentioned in the Rig Veda. Said to flow from the Himalayas to the Arabian Sea, the Saraswati eventually disappeared, leaving only traces. The Drishadvati is also mentioned in the Rig Veda as an important tributary of the Saraswati.

“Drishadvati is a Vedic river and was the only water source near Rakhigarhi,” said AR Chaudhri, professor at the Centre of Excellence for Research on Saraswati River at Kurukshetra University. “It is from the time of the Mahabharata.”

Manjul, who started excavating Rakhigarhi in 2022, said that the Drishadvati was once a lifeline for the region. The findings, he added, point to advanced techniques employed by the Harappans for water storage. Previously, the site had been excavated multiple times by archaeologists Suraj Bhan, Amarendra Nath, and Vasant Shinde. The discovery comes almost exactly 100 years after archaeologist Sir John Marshall identified the Indus Valley Civilisation in 1924.

“About 5,000 years ago, when the river started drying up, people needed to store water for their personal needs, including agriculture,” said Manjul. “These findings will give us an idea of the pattern of water management and how a society used to think.”

Rakhigarhi has become a crown jewel in India’s archaeological landscape. Discoveries from nearby sites such as Bhirrana and Farmana have pushed back the origins of the Indus Valley Civilisation by at least 2,000 years.

Also Read: Ratnagiri to Ramanathapuram—engineers, teachers, fishermen are ASI’s unsung warriors

A guess and a groundbreaking discovery

An informed hunch led to the discovery of a Harappan story of ingenuity and survival.

Since 2022, Sanjay Manjul’s team had been busy excavating ancient mud-brick structures at Rakhigarhi’s Mound 3, located between Mounds 1 and 2. Then in 2023, the idea to excavate the open area at the periphery of the same mound came to his mind. If there was an ancient reservoir, he reasoned, it would likely be located away from the mounds, in an open area separate from human settlements.

Manjul’s presumption turned out to be correct. His team found a siltation layer in 2023. But he needed more confirmation.

In December 2024, his team opened two more trenches to explore the size and scope of the reservoir system. And they found silt in these trenches too, strikingly different from the alluvial soil found elsewhere on the site.

Previous assumptions about the Harappan reservoir suddenly appeared small. This was bigger than anything found in the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilisation sites. It was one of the biggest breakthroughs since excavations began at Rakhigarhi in 1969 under archaeologist Suraj Bhan.

“Three layers of siltation have been traced. The accumulation of silt is proof that there has been stagnation of water there. But this is not the silt of the Chautang river, which means it was a storage area,” said Pankaj Bhardwaj, assistant archaeologist at the ASI’s Chandigarh circle, which oversaw the dig.

While Rakhigarhi’s drainage system was discovered earlier, no one had uncovered how Harappans stored water in later phases.

While the reservoir came later, during mature and late Harappan period, the drainage system on the Saraswati-Drishadvati was evident in all the three phases of the civilisation, wrote veteran archaeologist KN Dikshit in a 2013 paper titled ‘Origin of Early Harappan Cultures in the Sarasvati Valley: Recent Archaeological Evidence and Radiometric Dates’.

Three layers of siltation have been traced. [It’s] proof that there has been stagnation of water there. But this is not the silt of the Chautang river, which means it was a storage area

-Pankaj Bhardwaj, assistant archaeologist at the ASI’s Chandigarh circle

Unlike the Mesopotamian and Egyptian sites where canal systems were mostly designed for rulers, the large Harappan reservoirs in Rakhigarhi and Dholavira were meant for common people. Experts say that this was to reduce conflicts over water access.

“The concept of cleanliness and wells and drains is not so much about hygiene but conflict avoidance. So this is a strategy to keep people from fighting each other,” professor Jonathan Mark Kenoyer said in 2016 during an India visit.

Bhardwaj added that copper fishhooks and marine shells found in the Rakhigarhi trenches gave further glimpses into the Harappans’ daily lives and trade.

Thousands of years ago, the Drishadvati River coursed through the heart of Rakhigarhi and served as a lifeline for the ancient Harappan civilisation.

A site that’s rewriting history

Over the last two decades, Rakhigarhi has become a crown jewel in India’s archaeological landscape. Discoveries from nearby sites such as Bhirrana and Farmana have pushed back the origins of the Indus Valley Civilisation by at least 2,000 years—from the previously estimated 4000 BCE to 6000 BCE.

The site has also stirred debate over the years. Genetic testing on a 4,600-year-old skeleton of a woman reignited discussions about the Aryan invasion theory in 2019. The results showed no “detectable ancestry from Steppe pastoralists or from Anatolian and Iranian farmers” in her remains.

“The region of Haryana has so far provided the earliest radiometric dates in comparison to other parts of Harappan civilisation,” wrote KN Dikshit in the same 2013 paper.

As the ASI continues to unravel Rakhigarhi’s secrets, the site has become a hive of activity, with curious visitors coming to witness the slow, painstaking process of piecing together the past.

But for a site of such national importance, Rakhigarhi suffers from neglect. Although the 2020-21 Union Budget proposed developing it as an “Iconic Site”, heaps of cow dung fester throughout the area. Stray dogs, pigs, and cows roam freely around the trenches.

But the dig has captured the imagination of local schools and history enthusiasts.

On a chilly January afternoon, students from nearby villages watched intently as trained villagers dug the trenches.

“Isse kya pata chalega, itna gehra khoda hai (What will we know from digging so deep),” asked Shristi Sirohi, a 10th class student.

The answer was terse. “We are digging,” said one of the villagers.

Also Read: Villagers use Saraswati riverbed for cow dung, cremation, crop. ‘Where do we keep cattle?’

The vanished Drishadvati River

Thousands of years ago, the Drishadvati River coursed through the heart of Rakhigarhi and served as a lifeline for the ancient Harappan civilisation. Its waters shaped the landscape and nurtured the sophisticated urban centres that thrived along its banks.

“It was a crucial component of the region’s water management systems, supporting agriculture and daily life,” said professor Vasant Shinde, the noted archaeologist who led excavations at Rakhigarhi from 2011 to 2016.

However, over centuries, the Drishadvati faded into nothingness. Climatic changes and geological shifts caused it to dry up and disappear beneath the earth, leaving only traces of its once-mighty presence.

The river once flowed through the modern districts like Karnal, Jind, and Hisar before joining the Saraswati near Suratgarh in Rajasthan. Apart from Rakhigarhi, the key Harappan sites located along its plains include Sothi, Siswal, Mitathal, Balu, and Daulatpur.

Shinde said that two-thirds of all Harappan settlements are in the Saraswati basin—something that led to renaming the Indus Valley Civilisation as the Indus-Saraswati Civilisation, including in textbooks.

Also Read: 5,000-yr-old industrial hub—Binjor excavation shatters myths about ancient Indian manufacturing

An ‘unparalleled’ reservoir

One site that shows just how advanced the Harappans were at harnessing water is Dholavira, located in a semi-arid island in the Rann of Kutch.

At this UNESCO World Heritage Site, excavated by archaeologist RS Bisht between 1989 and 2005, discoveries included a network of stone channels that directed water from reservoirs to different parts of the city. Dholavira is also unique as the only Harappan site built entirely of stone. The people relied on two seasonal rivers, Mansar and Manhar, to sustain their water system.

Experts cite Dholavira as the finest example of Harappan water management. Reservoirs came in a variety of shapes and sizes— some were built in rectangle or circular designs and there were open reservoirs as well.

Vasant Shinde said that water was stored by diverting flash floods and building tanks inside the settlement. Dirty water was released outside the city through a channel.

“Such a system is not found in Mesopotamia or Egypt,” he added. “It is unparalleled.”

Meanwhile, in rain-drenched Rakhigarhi, a mini-tragedy unfolded in December. The trench had got filled with water and a section caved in.

“We have been working so hard for so many months here doing the arduous work of excavation,” recalled Bhardwaj. “We were almost in tears.”

Every day here is a race against time and elements. Bhardwaj will now apply for an extension for the dig.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)