New Delhi: Happy cries of “I win,” “Who has the dragon?” and “Who is the East Wind?” punctuate the click, clack, and clatter of tiles in a small room in Delhi’s Dhaula Kuan. At the Defence Services Officers’ Institute, a group of Army wives — all in their 50s – snap up and set down plastic tiles in quick succession until someone shouts “Mahjong!” And the game begins again.

This 19th-century Chinese offering is edging out traditional games like chess, carrom, gin rummy, and poker among social circles in Delhi and Mumbai. Once the mainstay of Army wives, Mahjong has now entered India’s wider elite circles.

“In the last year, the game has exploded. Everybody is playing it,” said Vineeta Sahni (66), a Delhi-based Mahjong teacher.

Having started the Mahjong India Facebook group eight years ago, Sahni is often approached by Army wives eager to master the game — a unique intersection of chance and skill. From parlours in Paris to lofts in New York, Mahjong remains one of the more popular games, even though it was banned for 40 years after the 1949 Communist Revolution in China because it represented “capitalist corruption.” And now, it has gained a foothold in India.

Country clubs are hosting interclub tournaments, restaurants are throwing social events, and experienced players are turning into teachers, advertising classes on Instagram and Facebook.

“Older people are aware that they need to improve their memory, which is why the game appeals to them,” said Sahni. For some, it’s a way to exercise mental acuity and motor skills, while others lean on hours of game time to catch up with friends.

Women, in particular, have taken up the game that was once predominantly played by men. In their houses in Gulmohar Park, New Delhi, and in the high-rises of Cuffe Parade, Mumbai, they are increasingly turning to the fast-paced tile game.

Even younger women in their 30s, tired of meeting only over drinks or food, are forming Mahjong groups.

“I didn’t expect to get so addicted to it,” said 30-year-old Mallika Punwani, a Mumbai-based brand consultant who is learning the game with five friends. “Lots of our friends play poker, but cards can be boring. Mahjong has different rounds, so you get variety.”

Mahjong spreads: Army wives abroad to circles at home

In Delhi’s upscale neighbourhoods, Mahjong is making its way into resident welfare association (RWA) groups and spreading rapidly through word of mouth.

“I hadn’t even heard the name ‘Mahjong’. But when I heard it had tiles, I was curious,” said Divya Rastogi, a retired professor who learned about the game on a morning walk with a friend in Gulmohar Park.

“It looked so difficult, so I wanted to try it.”

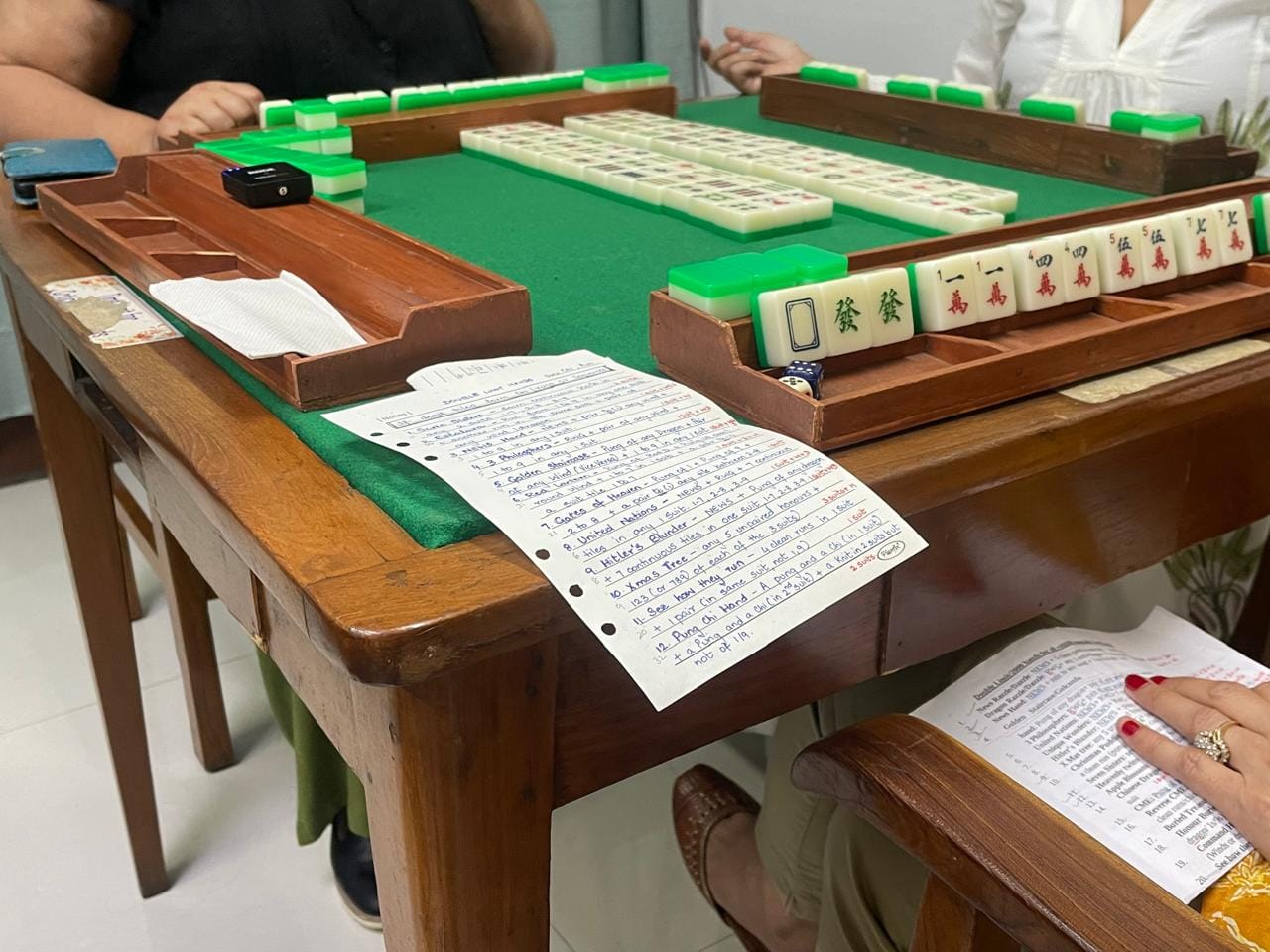

A traditional Mahjong set has 144 tiles, divided into suits, winds, dragons, and bonus tiles. Four players sit around a table, drawing and discarding tiles to complete a winning hand of 14. But it’s the combination of these 14 tiles that adds complexity to the game, with layers of scoring, bonuses, and variations that differ across styles of play.

Unlike board or card games, Mahjong’s steep learning curve requires an experienced player to hand-hold beginners — much like in chess.

Shalini Bhargava has been playing Mahjong for over 30 years and is now enjoying the wave of popularity the game is witnessing. At her house in Gulmohar Park, she patiently teaches three beginners, including Rastogi.

Over green tea and makhanas (fox nuts), Bhargava plays a two-hour-long game with her ‘students’. She gently reminds them of different hands, when to pick up a specific tile, or underscores a forgotten rule.

“Initially, when I started playing, it was an overwhelming amount of information to digest,” said Neena Maini, adding that there are 64 winning hand combinations to remember. “But at the end of the day, it’s a great social experience.”

Amid the clattering of tiles, loud cackles, and sips of green tea, Bhargava recounted how she first learned the game at a tea party in Kanpur. An Army wife had taught her, but she only recently picked it up again during the Covid-19 pandemic. She traces the game’s roots in India to Army personnel traveling abroad.

“There is historical evidence that it came from Army wives who went to England, Burma, and Southeast Asia along with their husbands and picked up the game,” said Bhargava.

The game also gained popularity in this close-knit community during stints in border towns like Dhulabari (West Bengal), Dimapur (Nagaland), and Shillong (Meghalaya). Here, Mahjong found its way across the border into local markets.

But whichever way Mahjong travelled to India, one thing is clear: the spouses of Army personnel were central to its spread. As for the game’s modern resurgence outside Army circles, Sahni points to advertisements on social media platforms encouraging people to “improve their memory.”

“People of that age are not as mindful, and they realise this, which is why the game appeals to them,” she said. At the DSOI club, her protégés gather in a room specially reserved for Mahjong, reminiscing about watching their family members play.

“Our mothers-in-law would play together, but we are picking it up now and using their sets,” said 54-year-old Chandni Singhal, gesturing to her two friends seated alongside her at the beginners’ table. “Post-retirement, we wanted something to look forward to besides a cup of tea and gossiping.”

All seven women in the room have husbands who are either serving in the Army or retired. And just like in Gulmohar Park, the one experienced teacher in the group is 57-year-old Anupma Nagpal. She heads the table with three other experienced players, who have been playing together since 2016.

The other table has three beginners. “The fourth player had to cancel, which has made us very upset,” said one of the women. All are clutching handwritten sheets of instructions. The notes act as cheat sheets, explaining the sets of tiles required for winning hands titled ‘Hitler’s Blunder’, ‘Mixed Noodles’, and ‘Chinese Dragon’.

“Maybe because we are nuclear families and when you are posted in different places there’s no support system,” said Nagpal, attempting to explain how the game picked up among Army wives. “Mahjong kind of became that support system for us.”

Nagpal and her group picked up the game across various cantonment towns — Pathankot, Jaipur, Jodhpur — wherever their husbands were posted. Although all of them now live in Delhi-NCR, they regularly travel across the country to meet friends posted in other cities, including Kasauli (Himachal Pradesh), Jaipur (Rajasthan), and Dimapur (Nagaland), just to play Mahjong.

“We were all limited to social media, watching TV channels, and scrolling on our phones,” said 54-year-old Ritu Mann, the newest member of the group, who started learning three weeks ago. “This way, we are interacting with each other and not using social media at all.”

Antique sets and private members’ clubs

At her house, Bhargava carefully opens the antique sets in her possession: wooden boxes with tiles made from bovine bone and bamboo. Each tile is crafted, carved, and painted by hand. She takes a magnifying glass to highlight the intricate patterns of Chinese characters, flowers, and symbols.

“There is a lot of symbolism associated with the game,” said Bhargava, clarifying that she doesn’t actively use any of the antique sets. “Some sets have beautiful tile designs where, if you place the tiles together, they form a garden or the Great Wall of China.”

Mahjong sets are also difficult to buy in India, where high-quality ones sell for upwards of Rs 20,000, compared to Rs 5,000-6,000 in Singapore. Older women still have sets passed down through the generations, or the means to purchase them. Nagpal owns five sets, most of which she bought abroad.

“It’s like jewellery; I enjoy collecting them,” she said.

Punwani managed to order one set from abroad, but she still depends on friends or teachers to play. Yet with the game’s growing popularity, Nagpal said it’s only a matter of time before good-quality sets become widely available in India at affordable prices.

Bhargava considers herself a purist of the game — she only teaches traditional Chinese Mahjong and vehemently dislikes modified versions that include “jokers” and other variations now popular in India.

Like its cuisine, the Chinese game has developed many iterations and interpretations as it spreads deeper into India.

“There’s a version called Mahjong Gita that is being played here,” said Punwani, laughing at the contrast between Indian variations and the original Chinese version.

Demand to learn the game has skyrocketed. Teachers are charging upwards of Rs 12,000 for ten sessions — a reflection of the game’s accessibility being largely limited to the urban elite. Sahni herself has recently started monetising her knowledge, teaching three batches of four women each, though she still primarily teaches for free.

The women learning the game at DSOI and Gulmohar Park aren’t paying for sessions either. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t taking them seriously.

“Women are so astute at playing this game — it involves memory, speed, skill, and strategy,” said Sahni, who compared Mahjong to learning a new language or sport. “It’s like golf. You just have to get into it and do it whole hog. Don’t follow it like it’s the latest fad.”

But there’s no escaping the Mahjong bandwagon, even in Mumbai. The Quorum Club, a private members’ club, hosted a Mahjong social two weeks ago. Greenr Café holds Mahjong events every evening at its outlets in Bandra and Breach Candy, offering tickets at Rs 500 per person, which includes one beverage from their “Mahjong menu”

Country clubs like Willingdon Sports Club, the Cricket Club of India, and Wodehouse Gymkhana are all offering Mahjong classes and tournaments. Even in the nation’s capital, the Delhi Gymkhana Club has seen a surge in members playing the game.

“We still have fights in the Gymkhana Club because the tiles make a lot of noise, which disturbs the bridge players,” said Sahni.

(Edited by Prashant)

Well the rich aunties are having fun in their kitty parties