New Delhi: Breakfast is forgotten. Sleep is negotiable. What Anil Gandas never ignores is his phone, because on the other end, there’s almost always panic: a cobra in the kitchen, a leopard in the fields, a python strangling livestock. Within minutes, the 49-year-old animal rescuer is in his Scorpio, a jeep that doubles as a rolling jungle. When he returns, the trunk is alive—cages rattling, ropes and hooks tossed around, a snake hissing, a lizard or civet cat thumping against its crate.

Gandas doesn’t just live in Gurugram, he patrols the city like a one-man wildlife unit.

“The vehicle is on standby 24/7, fully equipped. Sometimes there are so many rescues lined up that the entire day just slips away. There hasn’t been a single day without at least one call,” Gandas said.

Beneath Gurugram’s glass towers, luxury condos, and gated colonies lies ancient land once populated by leopards, snakes, and countless native birds. Long before highways cut through the Aravallis, the wild ruled it. But with every flood, construction site, and shrinking patch of forest, wildlife is pushed further—prowling the fields, slithering into kitchens, turning up in basements.

And at the edge of India’s rapidly growing cities, where the urban sprawl meets this wilderness, two rescue heroes in Gurugram and Ghaziabad—Anil Gandas and Vineet Arora—answer urgent calls to rescue wildlife caught in human chaos. Neither government employees nor formally trained at first, they fill a critical gap in wildlife rescue and conservation. They are NCR’s wildlife superheroes, who exist in the spaces between modern urbanity and the stubborn rural that refuses to go away in 21st-century India.

Gandas, a self-taught rescuer, and Arora, who is working with Jeev Upkar Trust, and aspiring vet from Ghaziabad, represent a new wave of conservationists. Facing limited resources in India’s cities, they turn rising human-wildlife conflicts into acts of care. Gandas runs Environment and Wildlife Society, a Gurugram-based non-governmental organisation (NGO), where Arora works.

Hero of Haryana wilderness

One afternoon in Mohammadpur village near Gurugram, Gandas received a call. The voice on the other end was tense. A snake had entered their house in the morning and hadn’t moved since.

Gandas asked just two questions: “What colour is it? And how long?” He immediately knew it wasn’t venomous. “It’s harmless. You can guide it out yourself,” he told the person. But the family wasn’t willing to take the risk—they needed him.

Without stopping for lunch, Gandas grabbed two bottles of water and hit the road. Forty minutes later, he arrived with a cloth bag and his tools. The snake was hidden inside a stack of old bricks, and he calmly reached in to grab hold of it.

“It won’t harm you. It’s not dangerous,” he repeated, holding the snake as it coiled gently around his arm.

“Some people kill these snakes just because they think every snake is venomous. Many times, they kill them before I even get there,” he told ThePrint.

Finally relieved, the family offered him tea. When a guest arrived, they introduced Gandas as someone from the forest department. He corrected them: “I’m not from the forest department.”

It’s in moments such as these that the truth hits him—most people can’t even imagine someone doing this kind of work without being on a government payroll. They assume he must be getting paid by someone. That’s why they rarely ask him if he charges. They don’t think they need to.

It’s a tricky choice for him. “If I start asking for money, people will stop calling. If I say 100 rupees, then half the snakes will be killed before I get there. So I don’t charge. I go anyway. If someone offers something on their own, I accept. If not, I move on,” he said.

For Gandas, wildlife rescue is not a weekend hobby. It’s a way of life—into the wild.

“I have rescued 22-23 leopards until now, and for that, I work with the forest department team. They have a tranquilliser gun, a doctor, and a wildlife surgeon. And I have the experience,” he said.

He’s been in the thick of it—handling pythons, blue bulls, peacocks, and snakes. He trains forest guards and is even pushing for wildlife education in schools.

Snake charmers and forest guards

The journey began much earlier, in a small village called Gadoli Khurd, where he was born into a farming family.

His first rescue was almost accidental. He was just 15 years old when a snake fell into a well in his family’s fields. With nothing but buckets, sticks, and borrowed ladders, he managed to pull it out alive.

“I didn’t even know about the snake at that time, whether it was venomous or not. But I took it out and left it outside,” he said, looking back and admitting that it was reckless. But the moment lit a fire in him.

He continued to do rescue work, got certificates in the wildlife rescue training programme, went to the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) for academic programmes and the Wildlife SOS and Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) for on-field workshops.

Fifteen years later, he had registered an NGO in Gurugram under the name ‘Environment and Wildlife Society’. He began conducting reptile training sessions, taking school children on wildlife awareness trips, and rescuing everything from snakes to leopards.

He has caught 28 types of snakes in the NCR alone, rescued hundreds of deer and nilgais, thousands of peacocks, and recently handled an 11-foot python. India has around 360 snake species and he has seen most of them.

Back then, even the wildlife department depended on snake charmers to capture reptiles.

“When I started this work, there were no rescuers in the whole of Haryana. Even in the wildlife department, snakes were caught by snake charmers. They used to pay them. Then I started rescuing them,” said Gandas.

Eventually, the rescuer began training the forest guards himself.

But his passion doesn’t end at rescue. He’s vocal about awareness and education.

“People don’t know about snakes. And they haven’t been taught in our books. Even today, I have written letters to the Haryana government and the CM to make a subject for children on wildlife,” he said.

Gundas’ frustration is evident when he talks about the lack of infrastructure: “There is no rescue centre in Gurgaon. There is no wildlife centre, especially in NCR.”

For him, conservation is inseparable from politics. Years ago, he proposed a 500-acre leopard safari to the Haryana government, modeled on similar projects in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh. The same party ruled all three states, but Haryana showed no interest.

Now, at that exact spot in the Aravallis, a 1,000-acre leopard safari is finally being built.

‘All god’s will’

Leopard sightings on Gurugram roads and in residential areas have become more frequent, and snakes often turn up in homes after heavy rains. For residents, these encounters bring fear, and often end in violence against the animal. With no formal rescue centre, no trained staff, and no emergency response system from the state, the responsibility falls on Gandas. Unpaid and unrecognised, he has become the city’s unofficial wildlife first responder.

In 2025, the Haryana Forest Department confirmed that animal rescues rely on ad-hoc efforts. There is no 24/7 veterinary care, no equipped centres, and no permanent trained staff. The only structured response comes from the Wildlife SOS Transit Facility, run in partnership with the Forest Department. It offers a Rapid Response Unit for Gurugram, but the rescue effort in the region remains an NGO-led endeavour.

The state recently introduced new Wildlife Protection Rules to streamline permits and improve veterinary support. But activists and rescuers say that without proper infrastructure, trained teams, or emergency protocols, the rules remain mostly on paper. The animals keep coming, and so do the emergencies.

So Gandas took matters into his own hands. He started the Environment and Wildlife Society to bring structure to his work, but the experience has been far from ideal. While it gave him credibility, he’s frustrated by the lack of commitment in his team.

“They just want to show off. If you’re serious, you have to be in the field. You have to work 24 hours,” he said.

And often, he does.

He’s seen volunteers and students show up full of passion, only to leave days later. The work, he said, is demanding and unglamorous. During one rescue, he was bitten while saving a civet cat from being mauled by dogs. The surgery cost over Rs 30,000 and left his finger permanently damaged.

He shrugged it off. Part of the job.

His livelihood comes from real estate. He rents out properties—factories and small spaces—in Gurugram. It’s what funds his rescue work.

During the Gurugram floods this year, he once responded to 18 rescue calls in a single day. “No time to bathe, eat, or even drink,” he recalled.

Over the years, he’s worked on sharpening his skills. He trained at the Wildlife Institute of India, joined Animal Welfare Board programmes, and learned from experience. “I used to watch the Discovery Channel, read books. And now I know which part of Gurgaon has kraits, cobras, or rat snakes.”

Covering Gurugram, Patodi, Sohna, Delhi, Alwar, and even Faridabad, Gandas stretches himself thin. Rescue work consumes his summers, often carrying into late nights, while winters give him his only respite. Among fellow rescuers, he sees many dabbling part-time, but very few who live it day and night the way he does.

And in his eyes, that’s the real crisis. “There is a shortage.”

Also read: World Baniya Forum wants to mentor the next Adani, Ambani. Post-1991 India is about hustle

Rescue and reform

Across state lines, in Ghaziabad, another rescuer walks a path equally committed.

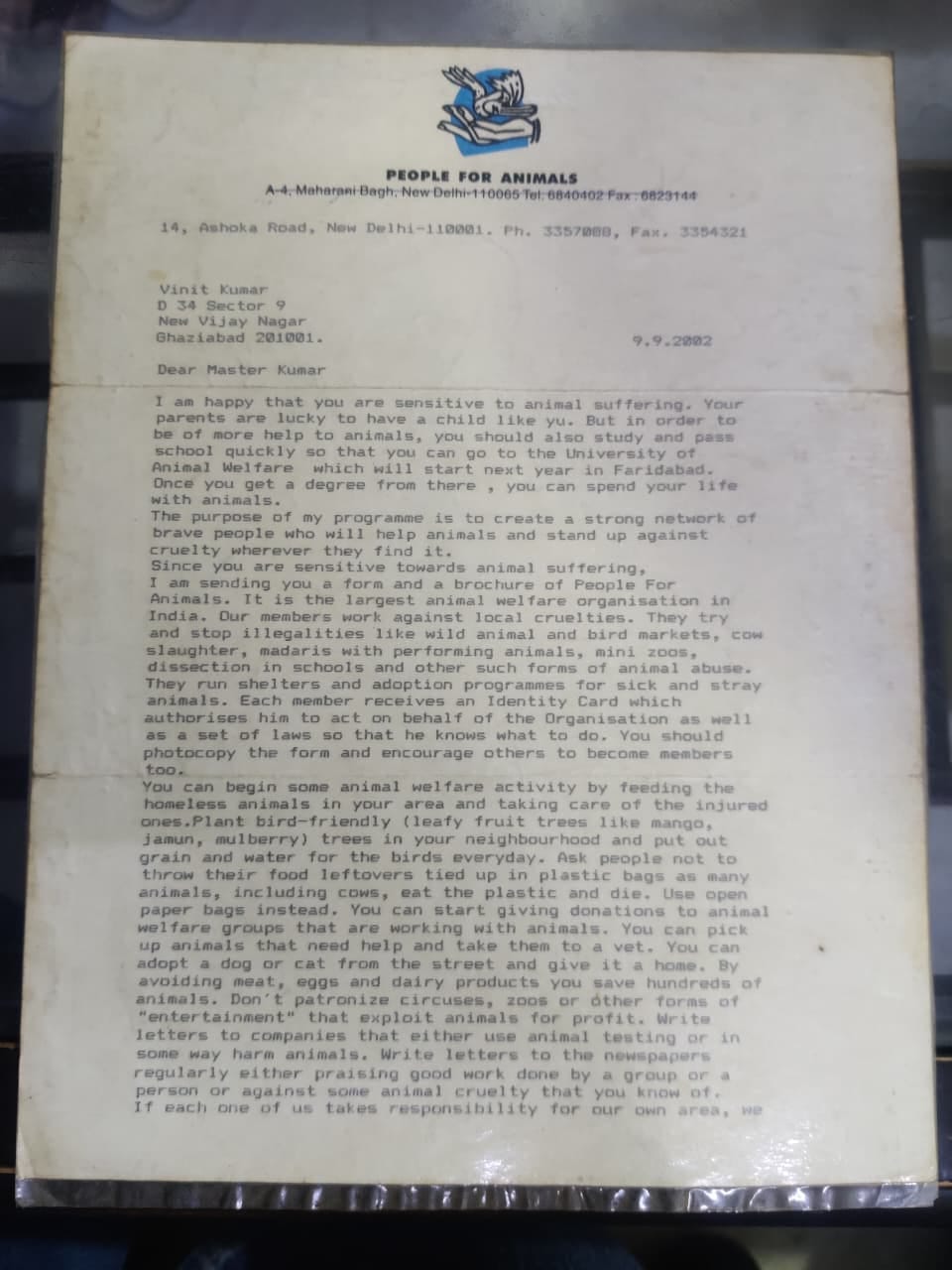

Vineet Arora, now 42, was 18 years old in 2002 when he wrote to Maneka Gandhi, unsure how to help animals, but desperate to do more. He got a response in the form of a letter.

“You can start giving donations to animal welfare groups. Pick up animals that need help and take them to a vet. Adopt a dog or a cat from the street and give it a home. By avoiding meat, eggs, and dairy products, you save hundreds of animals. Don’t support circuses, zoos, or other forms of ‘entertainment’ that exploit animals. Write to companies that harm animals or use them in testing,” she wrote.

Maneka Gandhi had recently been removed from the post of Minister for Animal Welfare, a position she held since 1998 when the animal welfare ministry was created for her by then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee as a condition for her joining the ruling coalition.

He hadn’t studied veterinary science then, but he started where he could—on the ground. He volunteered with NGOs, attended training camps, and worked with doctors, handling animals himself. Now, he’s preparing to pursue a formal veterinary degree.

“The first snake I rescued was a black-headed royal. Still the most beautiful I’ve seen,” he said.

Arora began with snakes, which he thought were misunderstood creatures. But he wanted to do more. It led him to join an NGO, which works on the welfare of animals.

Photography became another medium for Arora to connect with animals. After Covid-19, he bought his first camera, and now he spends early mornings in fields and sanctuaries across Surajpur, Sultanpur, Gurugram, and Rajasthan.

His mother, Asha, remembers a time when a bird had died and Arora gave it a full burial, making a cross from paper to use as a ‘headstone’.

Nearly 30 years later, he witnessed a convoy of trucks packed with buffaloes—stacked and crushed. He called the police on the spot and saved the animals.

While Arora committed himself to NGOs, Gandas carved his path through politics. But both have the same goal—to make sure animals don’t get the short end of the stick in human-animal conflicts.

Gandas joined the BJP in 2000. He is now the vice president of the Environment Department in Haryana. Politics, he says, has helped amplify his conservation efforts.

(Edited by Prasanna)