Jamtara: The police descended on the tiny village of Siyatand in Jamtara. But residents of the district did not hide, huddle, or hunker for cover. There was no lathi charge, no chase across the fields. It was a different kind of visit.

“That day, police did not come to arrest anyone or to conduct raids. They came to talk to us, to teach us about what else we can do to earn money. They showed us an opportunity and I took it,” said 23-year-old Sonu Mandal.

A day after the police session, he joined the new library in the area.

The programme Sonu attended is part of a collective effort by the authorities to exorcise the Jharkhand district’s notoriety as India’s cybercrime capital. Mythologised on Netflix and in popular memory as ground zero for digital scams, Jamtara is undergoing a makeover today. Once home to 19th-century social reformer Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, who established schools in this region, the district’s reputation has since taken a hit. Now, the state machinery is working to reclaim its status—one that had nothing to do with phishing or fraud.

Everyone from senior police officials to the district administration, politicians, and village elders are part of this drive. Over the last one year, the police and administration have held at least 10 awareness camps, public outreach events, and internet literacy programmes. They’re roping in local influencers. They’re converting disused buildings into libraries and study centres. They’re holding community programmes, conducting counselling sessions, and holding coaching classes for students appearing for competitive exams. So far, the district administration has opened 118 libraries, with one in every panchayat.

More study circles and informal career guidance centres with books and Wi-Fi are on the cards. Former Jharkhand chief minister Champai Soren has publicly supported the initiative, calling cybercrime “a social problem, not just a legal one”. Local MP Vijay Hansdak has also pushed for better digital infrastructure and skilling initiatives under the district’s action plan.

At the same time, police have intensified crackdowns and raids to break cybercrime cells. Over 300 arrests have been made in the last six months.

“We are using a two-pronged approach—making sure that no cyber criminal is spared, while also educating and empowering youth to choose lawful career paths,” said Raghvendra Sharma, a probationer IPS officer. Their efforts are paying off.

For a long time, no one told us we could do something with our lives and become something. I never thought a police station could become a place of learning

Sonu Mandal, Jamtara resident

“Jamtara used to be at the top of the cybercrime chart in the country. But after many raids, arrests, and awareness drives, it is now number 14 on the National Cybercrime Reporting Portal’s list. We aim to remove it from the top 50,” said Dr Ehtesham Waquarib, superintendent of police, Jamtara.

As many as 80 villagers, most of them young men in their early 20s, attended the outreach session at Siyatand’s panchayat ghat. Some sat upright on plastic chairs, others leaned against the walls, a few stood at the back, nodding as the police spoke.

It was a stark contrast to Jamtara’s recent past.

“Can you guess how many cyber criminals were arrested from Jamtara in the last six months?” asked Sharma. “More than 300.” Everyone fell silent. “So it’s my sincere advice to you—convince the youngsters of your village to stay away from cybercrime. Jamtara police will help with career guidance and opportunities.”

For now, even basic things like access to books, someone to talk to, or even study plans are helping young men say no to crime.

Also Read: Make women pregnant, get rich—Bihar’s cyber scam goes to a whole new level

Jamtara goes legit

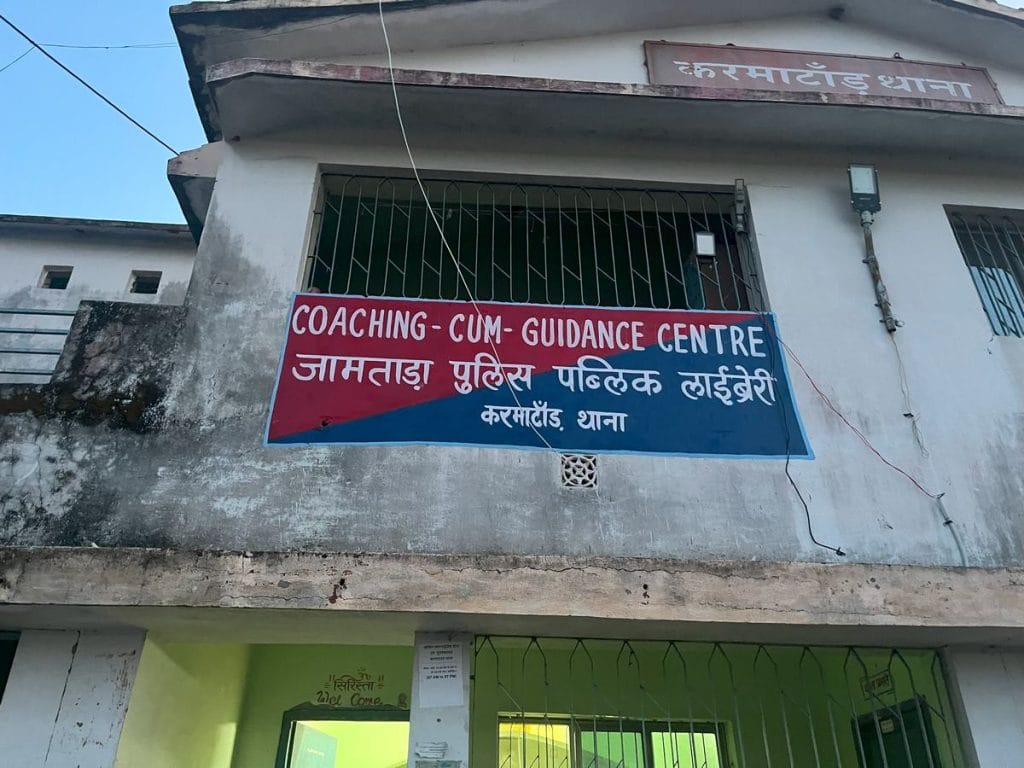

The library Sonu joined was set up by the police in an abandoned building that was once the Karmatand thana. He has a Bachelor of Arts degree, but didn’t know what to do with it. Cybercrime was the mainstay for young people in Karmatand block, where his village is located. More than 100 arrests have been made from just this one block in the past ten years.

“For a long time, no one told us we could do something with our lives and become something. I never thought a police station could become a place of learning,” said Sonu, flipping through a general knowledge book. “That old thana is now where I spend most of my day, but not in fear.”

Like Sonu, 22-year-old Ranjan Mandal from a neighbouring village is also struggling to get a job after graduating in history honours from Jamtara College last year. But he did not know what to do with his degree either. For several months he looked for a coaching institute nearby to prepare for a railway job but could only find centres in Ranchi, which he could not afford.

Now, he comes to the new library to borrow books and is being mentored by police officers. The library has around 150 books on general knowledge, history, political science, and competitive exam preparation — everything they need to study for entrance tests.“My father told me about this library. Our neighbour comes here too. When I told the police officers about my aspirations, they helped me prepare a study plan to clear the railway exam,” said Ranjan.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the digital payment method UPI in 2014, the youth of Jamtara saw it as an opportunity to make a fast buck. But it wasn’t a regular, salaried job. Instead, they came up with innovative ways to scam people—from fake SIM cards and cloning apps for siphoning funds to creating mule accounts to receive and move stolen money, especially through phishing and UPI fraud. These accounts were usually opened in someone else’s name, using fake documents or by tricking victims into sharing their credentials.

Our work is not done. Cybercrime is still there. We are making collective efforts to eradicate it

-Ehtesham Waquarib, Jamtara SP

Many elders in the district didn’t realise that what the youth were doing wasn’t honest work. That they were dreaming up scams that would bring shame to the entire region. Over the next seven to eight years, Jamtara became infamous as the cybercrime capital of the country. As the scams got bigger, bolder, and more brazen, it even inspired National Award-winning director Soumendra Padhi to create the hugely popular Netflix show Jamtara: Sabka Number Ayega (2020). “Jamtara ka sabse bada export hai confidence” (Jamtara’s biggest export is confidence) was one of the most popular lines from the series and once defined the region’s reputation.

For job seekers like Raju Tirki, Jamtara’s ongoing image makeover is a huge relief, especially when they travel out of the district seeking work. It’s hard to shed the stigma and prejudice that follows them everywhere. Jamtara has become the byword for cybercrime, and potential employers would reject them just because they were from the district.

“I went to seek work in Bhopal. I didn’t get a job because I am from Jamtara, and when I wrote my address in the hotel notebook, they refused to let me make an online payment,” said Tikira, 39.

It’s this reputation that the administration is determined to dismantle. The new library, managed by the district police, was set up three weeks ago at a cost of Rs 30,000. It’s equipped with Wi-Fi, a projector, and a screen as well.

Until about a decade ago, many families believed their children were doing legitimate call centre work, according to SP Waquarib.

“People here did not know that making fraud calls and defrauding money using the internet was a crime,” he said, adding that the police are changing the narrative one village at a time.

The fear of raids, arrest, as well as the awareness camps finally convinced Vikas Mandal to give up petty cyber fraud. He now runs a small grocery shop in his village, though making less money rankles him, he’s glad he can sleep in peace.

“Back then, I earned more than Rs 2–3 lakh in just a few weeks. But I invested that money into this shop. Now, I earn honestly,” said Mandal, a father of two.

Like him, a few ‘reformed’ cyber criminals have invested their past earnings to set up legitimate livelihoods, opening clothing shops, gyms, and kirana stores.

“They built houses, bought ACs and fridges with that money. And when the crackdown began, they quietly exited cybercrime and started small businesses. Some are still fighting cases in court,” said a resident of Karmatand, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

Police and district officials are showing young men what’s available in sectors ranging from banking and the railways to even the police force. “We can show them a path, but we can’t promise where it will lead,” said a local constable.

YouTubers show the way

Last month, when police SUVs roared into Subdidih village, just 12 km from Karmatand, villagers thought it was another raid. They braced themselves for the sounds that usually followed: the thud of boots, lathis cracking against walls, police shouting orders, villagers scurrying away. But this time, the officers didn’t bring lathis. They brought four YouTubers.

They were celebrities among Jamtara residents, who watched their reels and videos on their mobile phones. They made videos on food, daily life, and tourism in Jharkhand. The police had brought them to deliver a message: use the internet for positive purposes.

Over the next hour, the influencers showed villagers how the internet could be a gateway to legal job opportunities. They spoke about shooting videos on basic phones and gradually building monetised platforms.

“It took me more than a year to get decent views on my videos. I kept going. I knew that if I kept creating content, I would succeed. Everyone knows me in Jamtara now, and people invite me to their weddings. I’ve also started earning money. It’s not much, but it will increase slowly,” said Uttam Kumar Pandit, a 19-year-old YouTuber from Jamtara, who has around 4,000 subscribers.

More than 50 people, young and old, gathered to listen to the session.

“So many of our boys are already in jail. We don’t want the same fate for their children,” said one village elder.

“When the police came, we thought it was some trouble. But this time they came to educate our children. I made sure that every kid in the village attended this,” said Vikas Mandal while putting his hand on his son’s shoulder. IPS probationary officer Raghvendra Sharma was part of this outreach as well.

The administration can’t guarantee jobs. People like Ranjan and Sonu already have degrees, yet they’ve spent years struggling to find stable employment. Coaching centres are far away, competitive exams are unpredictable, and most families can’t afford to send their children to cities.

But the police and district officials are showing them what’s available in sectors ranging from banking and the railways to agricultural entrepreneurship and even the police force.

“We can show them a path, but we can’t promise where it will lead,” said a local constable working on the programme. For now, even basic things like access to books, someone to talk to, or even study plans are helping young men say no to crime.

Monthly crime review meetings conducted by senior officials of IG rank, better coordination with police from other districts and states, and the Samanvay portal—a data-sharing platform for cybercrime activity— are all part of the crackdown.

Also Read: The Great Indian Passport Scam: Labyrinth of fictional identities, expert forgers & pliant system

The beginning of a reformation

It took the administration more than half a decade to dislodge Jamtara as India’s cybercrime capital. And it’s still a work in progress.

In 2023, the nonprofit Future Crime Research Foundation (FCRF) analysed data over three years and found that Jamtara had been displaced by Rajasthan’s Bharatpur, which accounted for 18 percent of reported cybercrimes across the country. Nuh, Mathura, and Gurugram came next. Jamtara had dropped to fifth place, with 9.6 percent of cases, but it remains a hotbed for phishing and online fraud.

“It’s a good thing that Jamtara is reducing cybercrime, but if we see the larger picture, we as a country are not doing that great. Cybercrime is shifting to other districts. Cybercriminals have just shifted base,” said a member of the district judiciary, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Based on data from 1 January to 4 March 2025, the National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal (NCRP) lists Jamtara as 14th among 74 cyber fraud-prone districts in India. The most affected district is Nuh in Haryana, followed by Deeg in Rajasthan. Jharkhand’s Deoghar, which borders Jamtara, is third, with Alwar in Rajasthan and Nalanda in Bihar rounding out the top five.

“Our work is not done. Cybercrime is still there. We are making collective efforts to eradicate it,” said SP Waquarib.

The police are now targeting larger gangs operating in the area. Their biggest breakthrough came with the arrest of six high school dropouts in their 20s, who were allegedly part of the infamous DK Boss gang, which is linked to more than 500 cybercrime cases and accused of defrauding thousands of mobile phone users of at least Rs 12 crore.

“This was the first big catch by police where we were able to get hold of cybercrime masterminds who ran a network of hundreds of ground-level criminals,” said Raghvendra Sharma, who led the team that caught the DK Boss gang in January.

Monthly crime review meetings conducted by senior officials of Inspector General rank, better coordination with police from other districts and states, and the Samanvay portal—a data-sharing platform for cybercrime activity— are all part of the crackdown.

One of the suspects arrested in the DK Boss bust, a 28-year-old man from Sonu’s village, Siyatand, was tracked down using the Samanvay portal. He had previously been arrested for phishing, but after three months in judicial custody in Jamtara, he was released and later resurfaced in Birbhum, West Bengal, Sharma said.

Back in Siyatand, Sonu recalled a time when boys were praised for picking up a phone and making money. That’s changing. Now, the focus is on books.

“For the first time, I can see a future,” said Sonu, flipping a page in his GK book, Samanya Gyan.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)