New Delhi: A young man, visiting relatives in Gumtara village near Pench National Park, stepped out to relieve himself on the night of 7 September; the next thing he remembers is being pounced upon by a wild animal and being taken to the hospital.

His injuries were not too deep, and he was soon discharged, but rumour spread through the Madhya Pradesh village and in the local media that he had been attacked by a tiger. Despite not finding any conclusive evidence of tiger presence, there was little the forest department could do at the point but assuage the public from panicking.

“In the last two and a half years, we’ve only had two incidents of tiger attacks on humans in this region. It’s very rare, but because of the hype created around it, any rumour related to a tiger naturally spreads faster,” said Rajnish Kumar Singh, Deputy Director of Pench Tiger Reserve. “Now you can’t expect samajh (common sense) from a tiger, but you can from humans.”

The rise in such attacks across India is driving two questions: Are India’s tigers becoming more aggressive? Is India running out of space for its burgeoning tiger population?

An estimated 3,682 tigers place India as the host to more than 75 per cent of the world’s tiger population currently, 52 years after Project Tiger began. This resounding success, though, has come with increasing tiger-human conflicts. Scientists, forest officials, and conservationists attribute it to everything from the nature of the terrain to a lack of prey base to an increased familiarity with human presence. But one thing’s for sure, according to the architects of Project Tiger — India is nearing its tiger carrying capacity.

“No one has actually given much thought to what exactly the current potential for a safe tiger population in India is now, and beyond that, how will we control them?” said YV Jhala, a conservationist and key figure in implementing Project Tiger. “And given how many tigers we already have, this question is a ticking time bomb.”

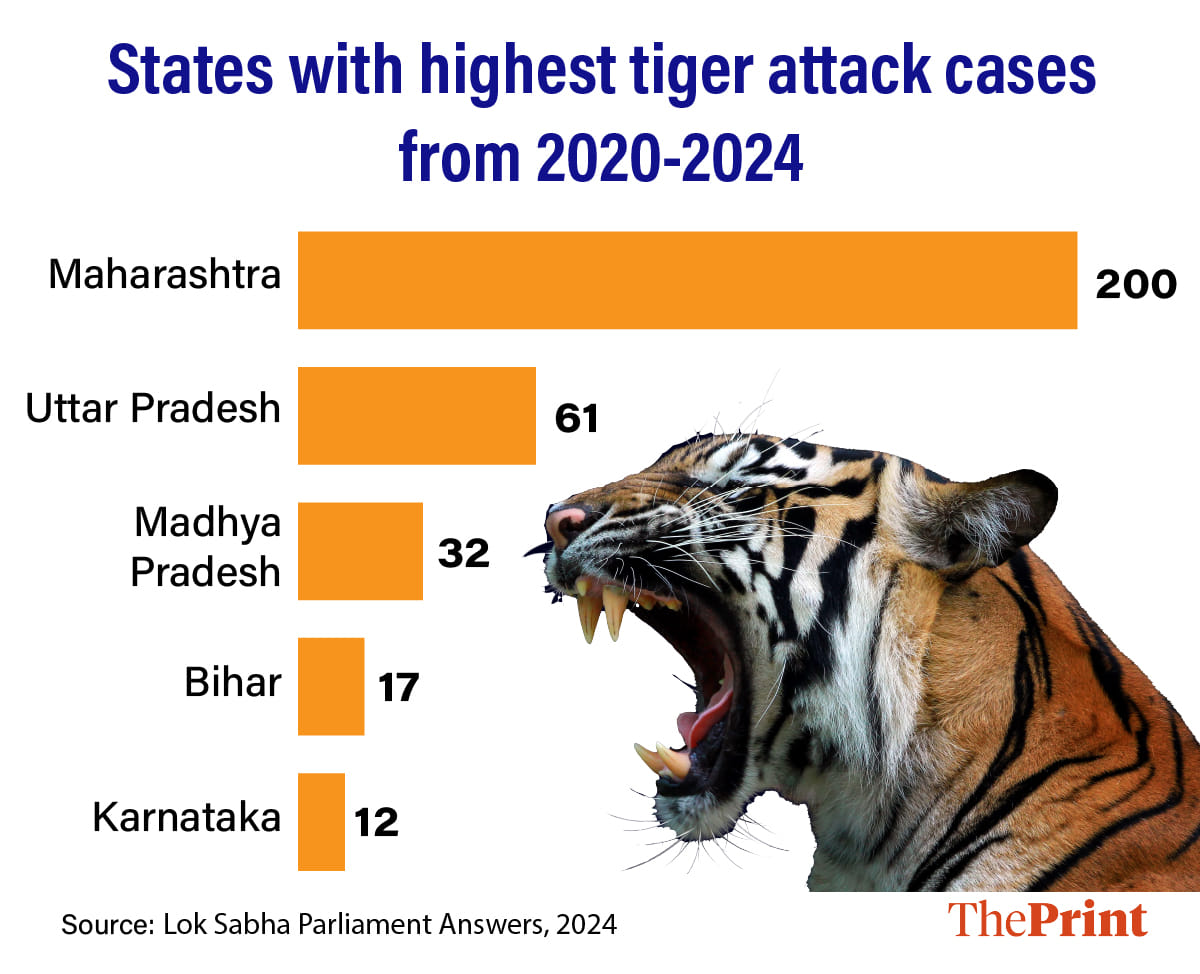

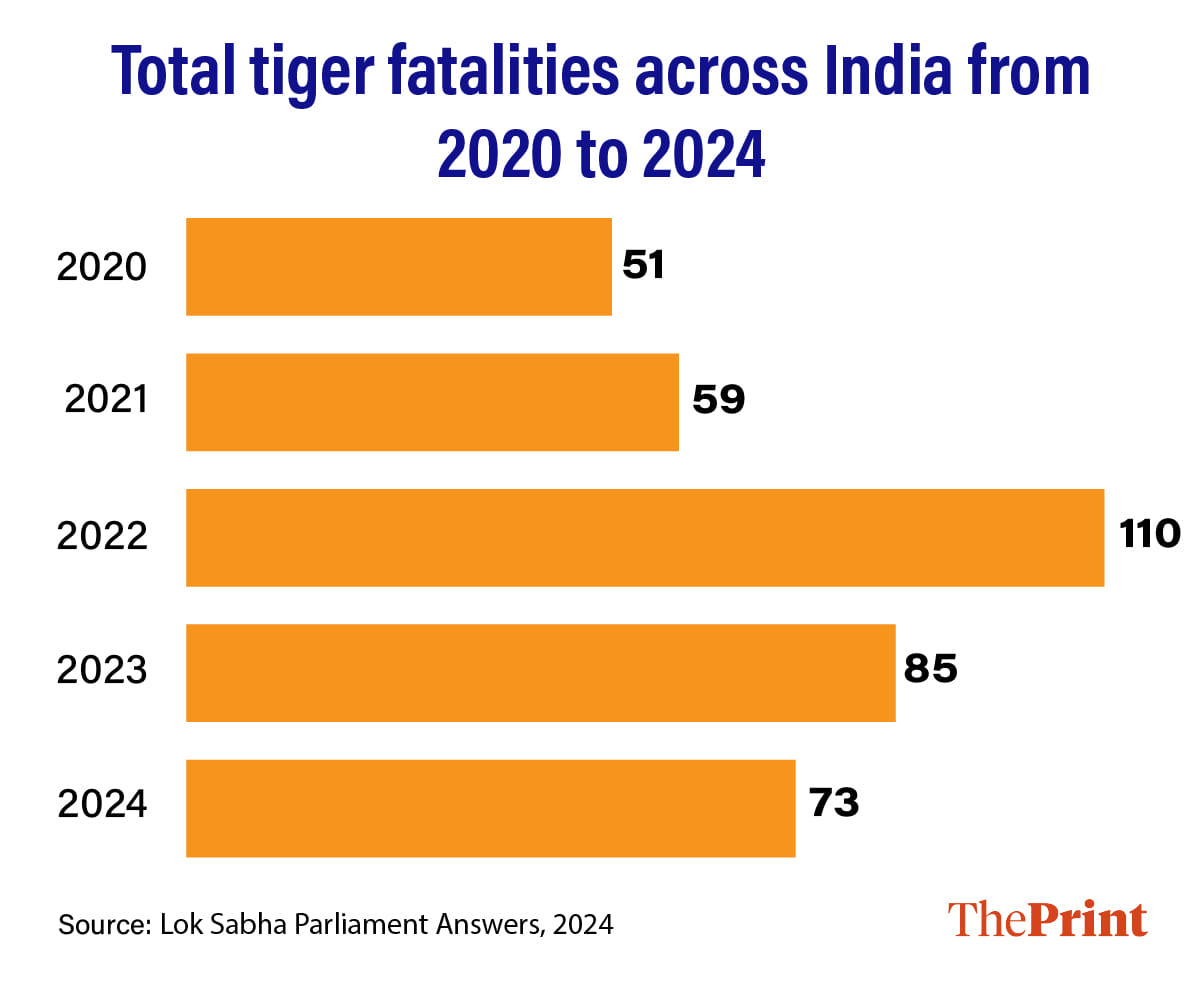

Gumtara would have added to the litany of incidents in the country this year where a tiger attack led to a human’s death. Last year, there were 73 such attacks in the country; the number has been in the double digits for over a decade now. Maharashtra, MP, and UP lead with the most cases, but this year, Rajasthan’s Ranthambore too has joined the ranks with three deaths in two months—something that has invited the National Tiger Conservation Authority’s involvement.

“What’s so great about humans that tigers won’t kill us? Everything is fair game; it’s just that for years, the tigers have been cultured to avoid humans,” said Jhala. “But culture can be changed. Tigers are learning that.”

Are rising tiger attacks a pattern?

A 74-year-old farmer, Pandurang Chachane, in Tadoba’s Chandrapur, and a 70-year-old priest, Radheshyam Mali, in Ranthambore, met similar fates this year — both were living near tiger reserves, out for work early in the morning, and both were killed by tigers.

But this is where their similarity ends. While one case is an age-old saga of humans risking their lives and venturing into tiger territory, the other is a more recent result of actions by forest officials that made tigers venture into human territory.

“No tiger is born a maneater; we don’t even feature within their food spectrum,” asserted Rajesh Gopal, Secretary General of the Global Tiger Forum and former national coordinator of Project Tiger. “But in the murky world of human-animal interactions, they can be lured, they can be conditioned, and they can become habituated.”

Chachane belonged to Maharashtra’s Chandrapur district, infamous for its tiger-human conflicts. Like clockwork, this year too Chandrapur has chalked up a long list of tiger victims, with 11 attacks happening just in May and Chachane’s being the latest one on 4 September. Maharashtra has remained the state with the highest tiger attacks, with most happening near Tadoba. In 2022, 80 per cent of the country’s attacks occurred in Maharashtra. But the attacks are never by the same tiger, and for the forest department, the case is an open-and-shut one.

Tadoba is one of the most densely populated reserves in the country, with 115 tigers, according to the latest estimate by the national park. If you add to that the rich teak and tendu forests and over 50,000 villagers depending on it, the stage is set for deadly encounters.

“These are not recent deaths. This is an old phenomenon that has been happening for the last 15 years. Most of these (May) deaths happened inside the forests because of the tendu leaf collection season of 15-20 days,” Dr Jitendra Ramgoankar, Chandrapur’s chief conservator of forests (CCF), had told ThePrint after the May attacks.

However, when Mali was mauled to death by a young tigress in Ranthambore – the poster child of tiger conservation in India – in June this year, the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) had to intervene. This was the third attack this year; the first two victims were a 7-year-old boy and a forest guard. They were suspected to be killed by the three cubs of the famed tigress Arrowhead, and after Mali died, the NTCA approved the order to relocate them to another reserve.

“With Ranthambore, the blame rests squarely on the forest management that decided to live-bait the tigers in the first place,” said Rajesh Gopal.

Citing the case of Ranthambore officials feeding live animals to tigresses Arrowhead and her grandmother, Machhli, when they couldn’t hunt, Gopal called it highly unprofessional and said it worsened human-animal interactions.

“Any tiger learns from their mother, and if the cubs saw Arrowhead being fed from a gypsy, they began associating people with the arrival of food, then little can be said about how they view humans now,” explained Gopal.

Context matters

The differing cases of the two reserves in Maharashtra and Rajasthan sum up everything that experts like Jhala and Gopal, and even other wildlife ecologists, have to say about tiger attacks in the country – context matters.

“Human casualties attributed to attacks by tigers occur under diverse circumstances. The only generalisation I would make is that most such occurrences happen when people unknowingly come in very close proximity to usually concealed tigers,” said Pranav Chanchani, a wildlife ecologist at WWF-India. “But even then, in most cases, neither the people impacted by the conflict nor the tigers themselves are at fault.”

To look for any one discernible pattern or reason connecting all the tiger attacks in the country would be a fool’s errand. It ignores years of research gone into understanding India’s forests, tiger behaviour and ecology, and their ever-evolving relationship with humans.

“Given our overall tiger population and the potential for conflict in this country, the actual rate is quite low,” said Jhala. “There’s no ploy by tigers to attack humans to eat them. Actual cases of ‘problem tigers’ that solely attack humans are quite low, and they are dealt with immediately by being put in wildlife centres.”

Another ‘hotspot’ of tiger killings is the Pilibhit Reserve in Uttar Pradesh. Over the past 7 months, Pilibhit has seen around 10 tiger attacks on people, largely in the sugarcane fields that dot the landscape. There were rumours of ‘man-eating tigers’ being released into Pilibhit, and the forest department even ordered to capture a tiger and translocate it. Jhala and Gopal had a much simpler explanation.

“The high grasslands of Terai look exactly like large sugarcane fields – when the fields are adjoining the forest, it’s unlikely the tiger will be able to tell the difference,” said Gopal. “When a human is hunched over working on the crops, it could very well be any other prey to the tiger. The attacks are purely coincidental.”

According to Jhala, the more pressing problem is to deal with the surrounding factors when tiger attacks come to the fore. The questions to answer are why tigers live so close to humans, why they leave forests to hunt, and how farms and buildings have taken over their habitat.

“We’ve changed their landscape and compelled ourselves to attach a pest status to the tiger — instead of our national animal, it’s now a national pest,” said Gopal.

Why prey bases are important

Most tiger attacks in the last decade can be directly traced back to a lack of sufficient prey bases in many tiger reserves, according to Qamar Qureshi, a professor at the Wildlife Institute of India and another pioneering figure in implementing Project Tiger.

“We might have 58 tiger reserves in the country, but barring a few, most of them are empty of biodiversity. They’re green deserts effectively,” said Qureshi. “We’ve spent so much energy shoring up tiger populations that we forgot about the other animals in the food chain.”

A 2025 report titled Status of Ungulates in Tiger Habitats of India, co-authored by Qureshi, paints a grim picture of this phenomenon. Ungulates are the herbivorous mammals, like deer, antelopes, and boars, that form the prey base of carnivorous animals. The report used data from camera trapping images from the Tiger Survey of 2022 to estimate ungulate populations in the reserves and found them to be sorely lacking.

The report found that chital, sambar, and gaur populations have declined in 27 per cent of all tiger reserves since 2014. Areas like Odisha and Jharkhand have low ungulate populations because of bushmeat consumption by local people. What was more concerning was that areas like Tadoba in Maharashtra, Ratapani in MP, and Valmiki in Bihar had very high tiger densities but low prey populations.

Qureshi explained that a tiger will naturally venture out in search of food if it doesn’t find it in the forest, and more often than not, it will venture right into an agricultural field or village next door to prey on cattle.

“It is a simple question – if you have tigers, which are naturally predators and naturally territorial – where do you expect them to go?” asked Qureshi. “You’re reducing their prey base inside the reserve, at the same time nibbling away at the forests where they live. What choice do they have but to then go to the next village and survive on livestock and cattle?”

Is India’s tiger appetite waning?

A hunting crisis, nine carved-out tiger reserves, Rs 3 crore, and a lofty goal — India’s Project Tiger in 1973 wanted to bring the beast back into business. Now, more than half a century later, the country is grappling with its burgeoning tiger population.

“India is already at its carrying capacity – maybe we have space for 500 more tigers, but we’re there already,” said Gopal. “If we get any more, you’ll be seeing tigers walking through East of Kailash,” he joked.

A carrying capacity is determined by how many tigers a landscape can sustain without overburdening the biodiversity. Tigers are territorial animals that need at least 50-100 sq km of space, and also a significant amount of prey. When any one reserve goes beyond its carrying capacity, it leads to territorial fights and deaths between the tigers.

“Right now, India’s tiger population is not spread evenly across all reserves. Some have abundant tigers and are seen as ‘sources’ from where tigers migrate and populate other areas,” explained Qureshi.

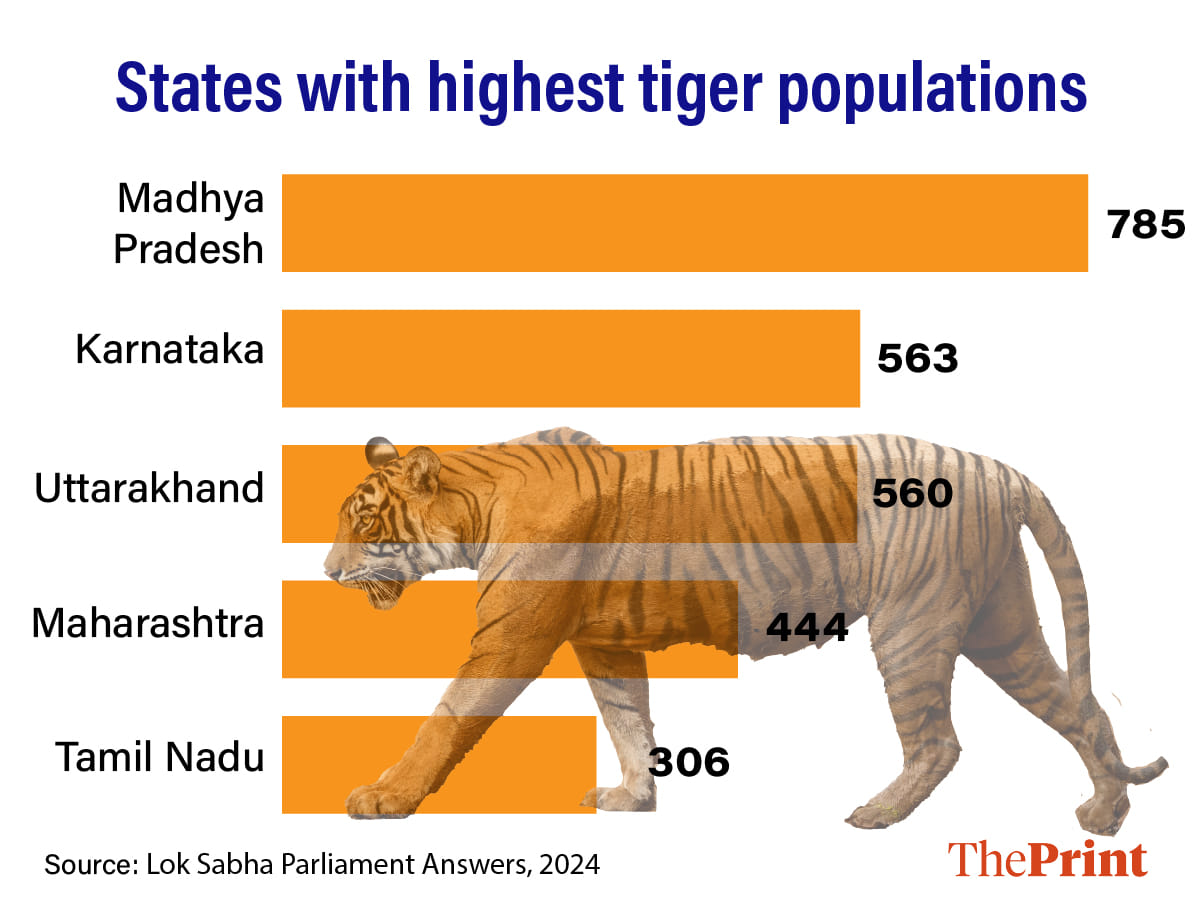

Reserves like Corbett, Ranthambore, Tadoba-Andhari, Nagarhole, Pench, and Sunderban are all close to their ecological carrying capacity. In terms of a state-wide population, Madhya Pradesh leads with 785 tigers, Karnataka and Uttarakhand following with 563 and 560 each. Maharashtra is next with 444 tigers.

The plan, according to Gopal, was always to establish a functioning tiger population and hope that nature would then take care of the rest.

“Tigers are naturally curious and venture out of their mother’s land soon after birth to find their own territory. Every reserve in the country is obviously not packed, but we have high-density and low-density areas, and we have ways for tigers to travel within them,” explained Gopal.

Unlike Jhala and Qureshi, however, Gopal isn’t worried about India ‘breaching’ its natural carrying capacity for tigers in the next few years. He believes that nature has a way of controlling these things by itself.

“There are signals of stress when any region has reached its maximum capacity of tigers. You’ll start seeing more territorial fights, more incapacitated cubs killed by male tigers, more tigers wandering out of their own territory,” he said. “That’s nature course correcting.”

Also read: DDA and Delhi University combo brought a biodiversity park revolution. Other cities envy

Tiger-human conflict

The case of Pilibhit’s and Ranthambore’s ‘problem’ tigers this year, though, highlighted another pain point in India’s wildlife conflict management strategy. Qureshi said that while putting away tigers in rescue centres is the current solution to manage this conflict, it is an extremely ‘short-sighted’ one.

“We’re not thinking about this either at a policy level or at a forest management level; instead, we’re brushing the issue under the carpet,” he said. “How many tigers will we put away until there aren’t any left?”

Instead, we should invest in making tiger reserves adequate for the animals, he said. The way to reduce human-animal conflicts, according to Qureshi, is to invest in studying India’s ungulates, building up prey bases and buffer zones inside reserves, and ensuring tiger habitats remain untouched by development projects. Cases like the recent order to alter the Sariska Tiger Reserve’s boundaries for mining are a reminder of how India is slowly chipping away at its tiger habitats, leaving the big cats with no choice but to come out.

“The solution rests in science,” said Qureshi. “Instead of quick fixes and scientists playing catch-up, science should lead the way in this new phase of tiger conservation in the country.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)