New Delhi: Ridhhaan Jaiin is in the middle of brainstorming ideas for his sixth novel. His research has led him to the depths of Indian mythology, where an idea clicked in his brain: What if Ravana never died but planned to return in Kali Yuga, the age of darkness?

“What if his death was a trick, and now he is getting stronger and regenerating,” said Ridhhaan, with the performative flair of a seasoned author, excitement rising in his voice. “I am thinking of making this into three books.”

Sudha Murthy’s Unusual Tales from Indian Mythology has influenced Ridhhaan, but his own approach will be different. After all, he’s only twelve.

Ridhhaan is part of a growing wave of child authors, writing everything from short stories and poems to fantasy and fiction. These books are not just being written for keepsakes or tucked away in cupboards. Driven by self-publishing platforms such as Notion Press, many are reaching other children across the country. The trend has also drawn interest from parents eager to capitalise on it, hoping it will help their children stand out in an increasingly competitive college admissions landscape.

Publishing a book has become a shiny line on a CV, like a black belt in karate or developing a mobile app. And there is now a small industry around it.

At this year’s Chennai Book Festival, a special stall was set aside for child authors for the first time. For about Rs 1,200, parents can enter their children into awards such as the Global Child Prodigy Awards. Small publishers run budding author programmes and writing contests. Platforms such as BriBooks offer templates and an “artificially intelligent helper” to guide children through writing a book and printing it on demand, with these accomplishments then shared on Facebook and Instagram. It even hosted a National Young Authors’ Fair this year. Schools are part of the circuit, posting photographs of their young authors, sometimes whole classes at a time, and stocking these self-published titles in their libraries.

Publishing giants like Penguin Random House also have their inboxes inundated with requests from eager parents. Many of these children aren’t ready to be authors yet, but publishing is the point rather than writing itself.

“Over the last three years, it seems that aspirational and enthusiastic parents motivate their children to publish their creative writings, sometimes even before their children have had the chance to polish their craft or discover their original voice,” said Kavya Wahi, Assistant Manager – Children’s Marketing, Penguin Random House.

Also Read: A Cloud Called Bhura to Hello Sun, Indian children’s fiction is telling climate stories

When precocity meets publishing

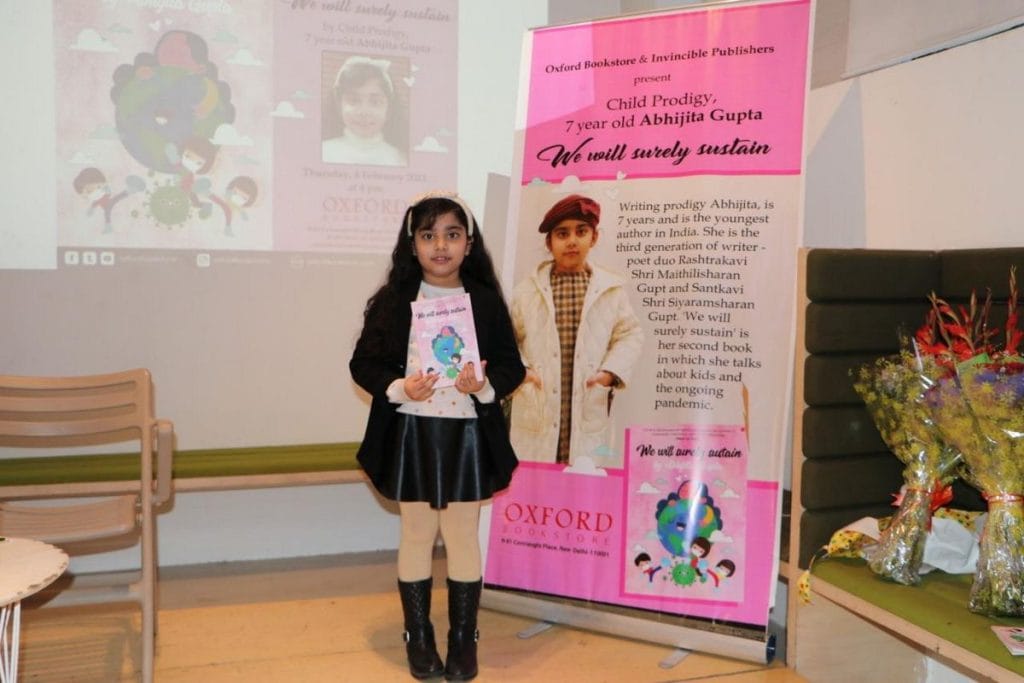

At seven years old, while most children can barely string together a coherent paragraph, Abhijita Gupta was sending her manuscript to publishers — ten of them, in fact. Nine rejected her outright.

“I saw a cartoon when I was five or six years old, where the main character was going to publish a book,” said the now 12-year-old Abhijita from her home in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. Inspired by the cartoon, she asked her mother whether she too could publish a book.

It was the tenth publisher, Invincible, that decided to take a chance on her after meeting her in person that same year.

Her first book, Happiness All Around, was a collection of short stories and poems inspired by the world around her, and dedicated to her father.

“Those were Covid days, so we wanted to limit screen time because she was very young,” said her mother, Anupriya Gupta, recalling when her precocious daughter started writing. “She came up with ideas and just asked for a diary and pen.”

Being confined at home during the pandemic also inspired Abhijita’s second book, We Will Surely Sustain, which explored lockdown hardships through a child’s eyes — missing school, playing with friends, and skipping birthday parties.

“We wondered whether she knew sentence formation properly enough to write,” laughed Anupriya, with a glint of pride over her daughter’s achievements. “But we were pleasantly surprised.”

For me, it’s not a medium of earning money but acknowledging my child’s work and encouraging his passion

-Vishal Jaiin, Ridhhaan’s father

Abhijita insists that she is old-school when it comes to writing. She’s quick to point out that she doesn’t ask her parents for help and shuns new-age tutors like Google and ChatGPT.

“I like keeping it authentic. I don’t want to add outside creations to my work,” she said with a hint of disdain. In 2022, Abhijita was the only writer among the awardees at the Global Child Prodigy Awards.

But not all children strike gold with publishers. For many, the only way to get their writing into the public eye is through self-publishing.

The business of writing

In Pune, Ridhhaan Jaiin not only faced rejection, but a lack of guidance and empathy from publishers.

“The whole journey was troublesome – publishers never understood the emotions of a child,” said Vishal Jaiin, Ridhhaan’s father. “For me, it’s not a medium of earning money but acknowledging my child’s work and encouraging his passion.”

Even when Vishal began working with a self-publishing service, he eventually took over the process himself, including finding an illustrator and editor.

“For them, it was just another commercial project,” he said.

Now twelve, Ridhhaan speaks about writing with a clarity that belies his age. His love of storytelling began at four, when one of his favourite pastimes was inventing stories for his parents and grandparents.

Like Gupta, Ridhhaan found solace in writing during the pandemic. The boredom drove him to write close to 90 stories. His parents encouraged him to type them out.

“Through this [typing], I re-read my stories and made them more interesting,” said Ridhhaan. “I played around with the setting, characters, and plot.”

The result was his first book, Once Upon in My Mind, published when he was eight.

I believe that there are many children who have even more talent than me. But it’s just that they didn’t get the platform

-Ridhhaan Jaiin, child author

Soon after, other children began approaching Ridhhaan for help publishing their own stories. Invited to schools and literary events as a young author, he found himself explaining the publishing world to peers. The family decided to turn that into a platform.

In 2022, they launched RidhzWorld Publishing to help other children publish their books. It also conducts ‘Once Upon In Our Mind’, a story-writing competition that has drawn over 4,000 submissions from 24 countries and published 28 young authors at no cost.

For the past three years, the contest has culminated in an anthology of winning short stories, released under the RidhzWorld Publishing imprint, with Season Four set to open soon.

The Jaiin family is steadily building an entire ecosystem around children’s writing, including mentorship programmes and a podcast titled B’coz I Can with Ridhhaan.

The show features Ridhhaan in conversation with artists and young authors, including a 10-year-old storyteller from Valsad, Gujarat, whose work appeared in Once Upon In Our Minds — Volume 3.

“I write what I observe. So, if I see a girl chasing a butterfly, that’s what I write about,” said Viva Mehta, the author of The Golden Butterfly, when Ridhhaan inquired about her inspiration. The conversation meandered into her other passions (fashion design), advice for other young authors and a rapid fire round.

“I believe that there are many children who have even more talent than me,” said Ridhhaan. “But it’s just that they didn’t get the platform.”

A new career ladder

For some parents, encouraging their children to publish is not about checking a box on a CV but about setting out a career path early. They point out that medicine and engineering aren’t the only options. Vishal Jaiin sees extracurriculars like karate and elocution as ways for children to learn skills that colleges and professional degrees won’t teach.

In India, nurturing a genuine interest in writing is challenging. Unlike cricket, where a five- or six-year-old child has clear pathways such as coaching centres, local matches, state teams, and national selection, literature has no well-defined structure.

“After all, Sachin Tendulkar didn’t play international cricket on day one when he held the bat,” said Vishal Jaiin.

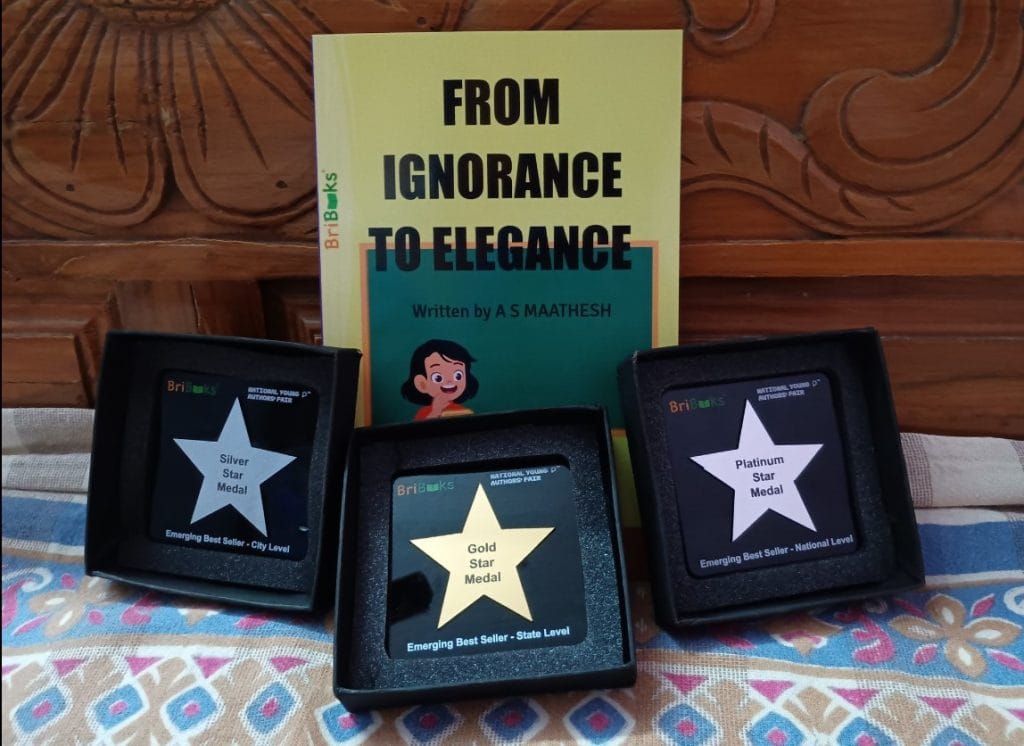

Children such as Abhijita and Ridhhaan are charting a path but new ventures are also moving into the vacuum, including BriBooks, which raised $1.5 million in pre-seed funding in 2022.

Co-founded by Ami Dror, an Israeli businessman, and edtech entrepreneur Rahul Ranjan, the platform offers AI-assisted writing and on-demand publishing for children. Through competitions such as its National Young Authors’ Fair, it sets out a clear ladder of progression: writing a book, publishing it, and then entering international festivals such as the Asian Festival of Children’s Content in Singapore, the Sharjah Children’s Reading Festival, and the Brooklyn Book Festival. Schools, too, share the authorial accomplishments of their students on social media as markers of academic clout.

National Young Authors’ Fair (NYAF) 2025–26! 📷📷

📷 Young Authors from St. Xavier’s Public School, Bagnan

📷 Selected entries will receive Certificates, Awards & International Recognition!#YoungAuthors #NYAF2025 #Xavierians #ProudMoment #GlobalRecognition #StudentSuccess pic.twitter.com/FckuMibSlg

— St. Xavier's Public School, Bagnan (@xaviersbagnan) November 10, 2025

In 2024, 14-year-old Keya Hatkar, who has spinal muscular atrophy, received the Pradhan Mantri Rashtriya Bal Puraskar for books on navigating her condition published through the platform.

But as publishing becomes easier and more accessible, questions of quality and gatekeeping follow close behind.

Also Read: India’s youngest spiritual baba wants no friends, smartphones. What about homework, people ask

‘A lot of FOMO’

Self-publishing helped 18-year-old Prisha Agrawal find her voice, but she is outspoken about the ChatGPT-fication of writing and how books are becoming more about credentials than craft.

Agrawal discovered her love of poetry and writing after joining an International Baccalaureate (IB) school in Mumbai.

“I’ve always grown up reading a lot. And surprisingly, writing was a part of literature that I never quite connected with,” said Agrawal. “[In IB], it was a very nuanced version of the subject that we studied rather than rote learning.”

With ChatGPT, with 21 prompts that you can copy and paste, you can have a published book in your name

Prisha Agrawal, writer

Agrawal’s first poetry collection happened almost by accident three years ago. She participated in a 21-day poetry challenge by Bookleaf Publishing, a self-publishing platform.

“I was one of the few winners who they had selected to publish in an anthology,” she said. That early work was a beginner’s attempt where she was “rhyming words here and there” but the real learning curve came with her second anthology, Eldest Daughter Sitting on a Pyre, where she didn’t only do the writing but also the structuring and cover design.

“I did this with [the self-publishing platform] Notion Press,” said Agrawal, adding that a friend who also wrote poetry edited the book. “That really taught me about the process of publishing a lot more, because that was something I had to do completely myself.”

But Agrawal is sceptical about the AI-powered boom in children’s publishing. She said it was “appalling” that anybody who takes part in a 21-day poetry challenge, which requires submitting a poem a day, and wins it is published.

“And with ChatGPT, with 21 prompts that you can copy and paste, you can have a published book in your name,” she said.

Agrawal estimates that 99 per cent of the young authors she has encountered published their books for the ‘wow factor’ rather than any artistic motive.

There’s an array of self-publishing platforms in India — Notion Press, BookLeaf Publishing, Pratlipi, I Am An Author, and even Amazon, through Kindle Direct Publishing — but Agrawal says she can now identify which ones are in it purely for vanity books.

The surge in child authorship is one symptom of a far more competitive admissions landscape, according to Akhil Daswani, co-founder of OnCourse Global, a college admissions consulting firm. Students today are pushed to specialise early. In that environment, becoming a published author has become “only a piece of the puzzle”.

“If you want to go into literature, of course it’s more credible if you are published. But not every book being published is of the same quality — it’s about how good the content is, do you have any credibility behind it and has anyone written about you,” he said.

At times, parents or other relatives are doing all the hard work. Even if their children aren’t writing, they are turning them into ‘published authors’.

“A friend’s mother made him publish one of his earlier books in their sister’s name, even though she had not written it,” said Agrawal.

Daswani has watched this pattern mirror what’s happening in research. Just as science and economics students now scramble to publish papers in academic journals, some of them dubious, students in other fields set about getting their names on coffee-table books and anthologies to build their resumes.

“There is a lot of FOMO in play,” said Daswani. “They [parents] see a neighbour’s child publishing a book, and wonder whether they should also do that for their kid.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Interesting to see, competitive exams irrespective of their flaws open floor for more percentage of population from top. also Goodhart’s Law in action

I guess most of them are zero in mathematics.