Moradabad: For many years, the Pataleshwar Mahadev Temple in the Muslim-dominated village of Bhamraua in Uttar Pradesh’s Moradabad was a mystery shrouded in whispered tales. Some said it dated to the Mahabharata era and others claimed the Mughals built it. The truth may have been lost in time until last year, when a remarkable discovery was made as part of the ambitious redux of the once-grand colonial project of the Enlightenment—researching and publishing district gazetteers.

This time, states are reviving the old practice minus the colonial gaze. The origin story of the temple was finally revealed during the Gazetteer of Moradabad division project.

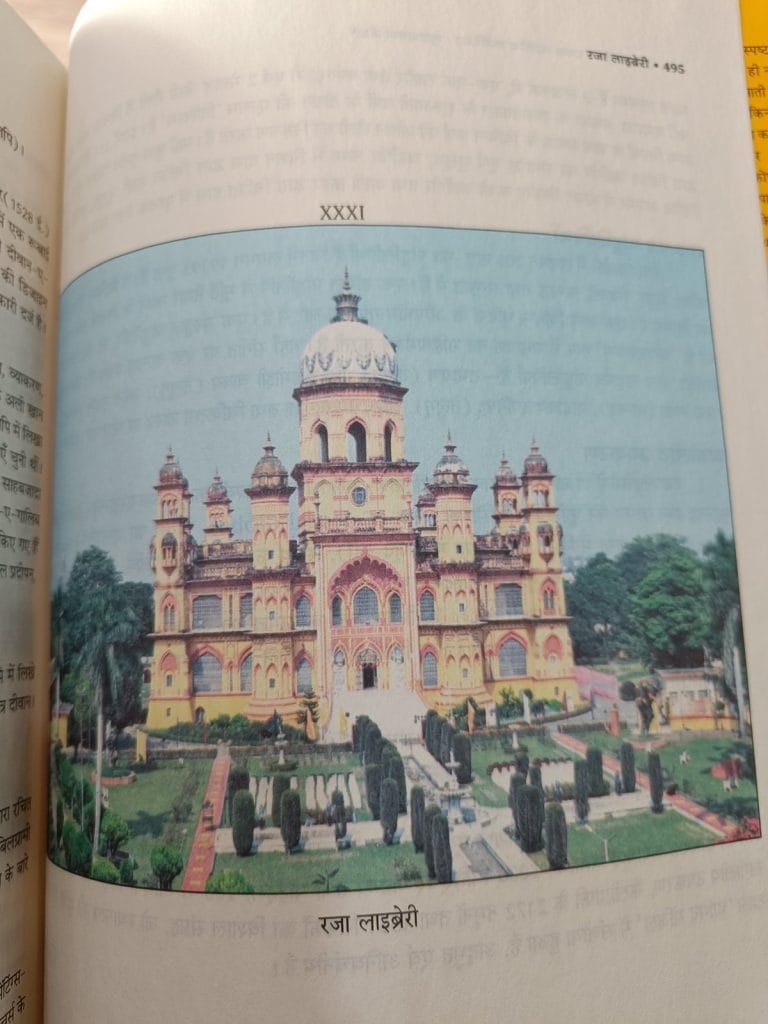

“At the archives of Rampur’s Raza Library, we found a century-old book titled Halaat Dehi Maujawaar Pargana Tehsil Riyasat Rampur that unravels the enigma around the temple’s past,” said Aunjaneya Kumar Singh, divisional commissioner of the Moradabad division, who spearheaded the making of India’s first division-level gazetteer. “According to the book, the temple existed in the village when the Taga population lived there. In the 18th century, during the reign of Nawab Ali Mohammad Khan, the Tagas were replaced by Sheikhs.”

A full page in the gazetteer is dedicated to the temple, laying out its history with archival references.

After a gap of nearly five decades, state governments are now pushing to write gazetteers beyond the lens of the Raj. Introduced by the British in the 19th century, the practice fell into disrepair after Independence but in the past few years, several states, including Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Haryana, have restarted the exercise to document district-level histories. The Uttar Pradesh government has also begun work on city-level gazetteers, among the first of their kind in India.

While British gazetteers focused largely on administration and revenue, the new exercise aims to create living records of culture, social change, and democratic life.

“From day one we were clear that we would take the best practices of the British, but our document would also cover other aspects of society, such as culture and schemes to understand the churning within the region,” said Singh.

But in several states, capturing these granular pasts and stories has been riddled with challenges stemming from poor capacity, methodological sloppiness in archival work, and exclusion of lived voices.

So far, Moradabad is the only big success as far as government efforts go. The only other project that has achieved the goal is a private initiative by Maharashtra’s FLAME University, which documented district-level information and published it online.

“If we compare the British period and the years after Independence, the administrative setup has totally changed. The British documented their period through gazetteers, but we did not. It’s important to document the journey of democracy and how the welfare state works on the ground. For doing this, the gazetteer is the best tool,” said Singh, showing the two-part Moradabad division gazetteer at his office.

Also Read: Modi govt’s The Kunj is making handicrafts luxe, aspirational. It’s no Cottage Emporium

A guide for Sambhal

In Sambhal, where the administration has been reworking the town’s identity around Hindu wells and pilgrimage sites, the gazetteer has become the latest addition to the project.

For the last two weeks, a team of 50 staffers from the Sambhal Nagar Palika has been going door to door to collect ward-level data from households.

“For the first time in history, a gazetteer at the Nagar Palika level will be made, and the work is in progress,” said Mani Bhushan Tiwari, municipal council executive officer of Sambhal.

The district administration has divided Sambhal into urban and rural sections. Tiwari is overseeing the urban documentation; work in rural areas is yet to start. Last month, in a meeting, it was decided to divide the town into five zones, with each assigned a nodal officer.

Teams on the ground are collecting data on population, ponds and waterbodies, public assets, roads, schools, industries, occupations, parks, and other public utilities.

“When we compile this data, we will get a multi-faceted picture of each ward in urban Sambhal,” said Tiwari. “This will help to plan policies specific to each area.” Once both urban and rural surveys are complete, he added, the administration plans to publish a complete Sambhal gazetteer.

The Sambhal exercise draws directly from the Moradabad division gazetteer, which has become a reference point across Uttar Pradesh. Work on the Moradabad gazetteer started in 2022, with the first volume released in 2023. It documents the division’s history, administrative structure, departments, cooperatives, and the Smart City Mission.

Last year, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath launched the second volume of the gazetteer.

“The Moradabad Divisional Gazetteer is an excellent attempt to compile both the history and present-day realities of the region,” he wrote in the foreword. “This gazetteer presents various dimensions of modern administration and development in an authentic manner, all in one place.”

Making of the Moradabad gazetteer

The 1911 Moradabad Gazetteer contains a grim snippet about girls’ education at the time. Referencing the 1872 census, it noted that only one female in Moradabad could read and write. The figure, if correct, it said, testified “to the inefficiency of the girl’s schools.”

It further observed that “owing to the large number of Muhammadan cultivators and labourers, Hindus are relatively better educated than Musalmans” and that on this side of the Ganges “the Persian script is more commonly employed than the Nagri.”

The British documented their period through gazetteers, but we did not. It’s important to document the journey of democracy and how the welfare state works on the ground. For doing this, the gazetteer is the best tool

–Aunjaneya Kumar Singh, DC of Moradabad

The Moradabad Gazetteer was first written by HR Nevill in 1911 and then revised in 1968. A civil servant and one of the most prolific gazetteer writers of British India, he authored district gazetteers for Bulandshahr, Moradabad, Nainital, and Aligarh in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. He was also among the founding members of the Numismatic Society of India, set up in Allahabad in 1910.

Earlier a district, Moradabad became a division only in 1980, with five districts — Amroha, Bijnor, Moradabad, Rampur, and Sambhal.

While the old gazetteers concentrated mostly on revenue, land settlements, and administrative systems, the brand-new edition attempts a broader sweep.

“We didn’t want to just copy-paste the methodology of the British. We want to deliver something new and fresh,” said Singh.

The British version was a “torchbearer” , he added, but execution was a challenging task. Singh divided the work into four teams: one to collect information, a second to verify it, a third to process the data, and a fourth to write the gazetteer.

“In a tech-driven era, society is taking new forms, and migration has become commonplace. Documenting this changing landscape was the biggest challenge,” Singh said, adding that the first volume was easier to complete than the second.

The second volume, titled Parampara ka Pratibimban (which translates to ‘reflection of tradition’), has nearly 400 pages and focuses on culture. It documents prominent places, crafts, industries, tribes, monuments of national importance, fairs, festivals, and libraries. It also accords space to the famous personalities associated with the region, including Zohra Sehgal, Jigar Moradabadi, Jaun Elia, and Sultana Daku, and traces musical lineages such as the Rampur and Bhendi Bazaar gharanas, with sources cited at the end of each section.

The district administration included the gazetteer project under the Smart City programme. After the data was collected, Singh brought in writer Nivedita Tomar, who had earlier worked with him when he was district magistrate of Rampur.

“Writing the project was an interesting experience,” said Tomar. “I worked in Rampur so I have some knowledge of this area, and my interest towards history and culture helped me.” She added, however, that documenting culture with credible sources for the second volume was a struggle.

Why gazetteers matter

Old gazetteers have not remained confined to dusty archives. The colonial Faizabad Gazetteer played an important role more than a century later in the Ayodhya Ram Janmabhoomi case. The Supreme Court cited its account of the Ramkot site as corroborative historical material identifying it as Lord Ram’s birthplace.

For scholars, gazetteers are important primary documents to understand local history. Historian and author Narayani Gupta recalled that research in the 1960s and 1970s was a far slower process, with no internet, limited access to printing, and restricted maps.

“For those of us working on local histories rather than national political stories, the gazetteers were glimmers of light. Books were easier to read than shabbily tagged files. The Gazetteers had a wonderful quality of literary elegance. They had all the information for geographical and community details, the work of government departments, maps, and evocative descriptions of villages, waterbodies, rivers, and hills,” said Gupta.

The British gazetteers still help for references and to know the background for many issues. The British recorded their time and it’s important for us to record our time

-Sanjeev Sanyal, economist

She cited the 1882 Delhi District Gazetteer for its vivid portrait of Mehrauli, the Khadar (floodplain), and village life along the Yamuna river.

“I wish it were compulsory for junior IAS officers to write accounts of their days as Collectors or Assistant Magistrates. Upamanyu Chatterjee is an example, but maybe there are others for whom the novelty of their rural experience can provide a unique window for understanding the spirit of the country, of the interaction between urban and rural,” Gupta added.

Maharashtra’s private success story

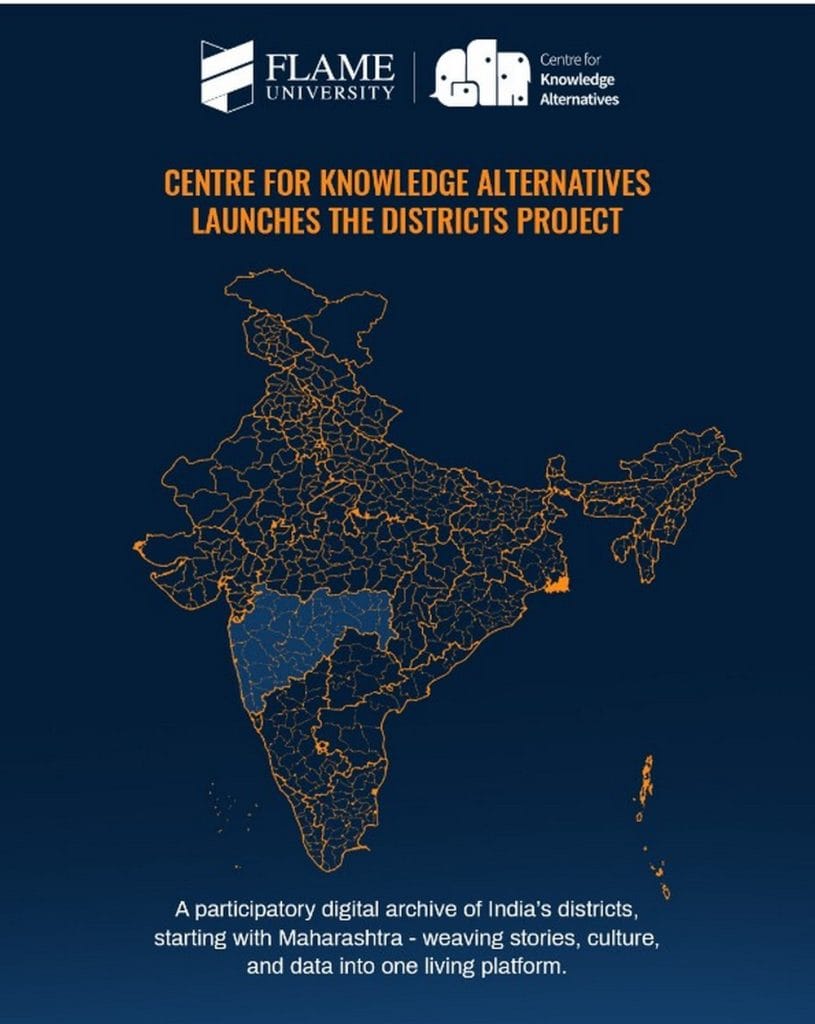

In a unique passion project, a professor at Maharashtra’s FLAME University has taken the district gazetteer out of government offices and into the digital era.

Economist and professor Yugank Goyal launched the Districts Project during the Covid-19 pandemic and took on all 36 districts of Maharashtra. The project combines official data with locally sourced material and seeks to create an online hub for the state’s districts and talukas.

“The British wrote about us in great detail, although with a colonial lens and biases,” said Goyal, adding that while India has broad national data, for talukas and districts, detailed, granular information is entirely missing.

“Our project fills that vacuum and its strength lies in its participatory model, which can be scaled easily to districts outside Maharashtra,” he said.

A team of around 12 people built the platform, dividing information into two broad categories: culture and statistics. The cultural section includes architecture, art forms, cultural sites, festivals, food, language, markets, stories, and sports. The statistics section covers agriculture, education, environment, industry, elections, health, and revenue.

Goyal’s team collated official data from district administrations, while cultural material was gathered through fieldwork. In 2024, FLAME University also launched a three-month district fellowship programme for the documentation of district-level statistics and cultures.

It is going to be ever-enriching when more and more stories come to us. We connected our project with the citizen, which was missing in the old system of gazetteers

-FLAME University professor Yugank Goyal

“We selected students from Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas and local colleges in each district and engaged them on the ground, calling them District Fellows,” said Goyal, adding that these students bring in stories rooted in local experience. It’s an all-new cache of hidden stories for India.

The Dhule district page, for instance, includes a profile of Amali village, known for its Vishnu temple and the Kanhaiyalal Mandir, as well as an account of freedom fighter Janardhan Sakharam Vispute.

“Janardhan once had the honour of sharing a coach with Mahatma Gandhi while travelling from Surat to Bhusawal. Gandhi advised him to boycott foreign goods, and Janardhan was moved by the great leader’s remarks. He also met Balubhai Mehta and worked as a clerk for Ghanshyam Laxmidas, a Gujarati lawyer,” reads the website.

Goyal said the cultural sections are crowd-sourced and open to edits.

“It is going to be ever-enriching when more and more stories come to us. We connected our project with the citizen, which was missing in the old system of gazetteers,” he said. Statistical data, he added, is acquired from district statistical offices and then made intelligible and digitised.

Goyal’s interest in this area started around 2016, when he was associated with OP Jindal Global University and worked on a Karnal gazetteer. It was never published but working with the old documents sparked a realisation in him.

“That’s when I understood how important local information is,” he said. “Then I started full-fledged work in Maharashtra.”

The project, though housed at FLAME University, is funded by Vallabh Bhanshali, co-founder of the ENAM Group, and Monik Koticha, managing director of Fortress Group.

On 1 December, Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran launched the project in Pune.

“The Districts Project represents a powerful step towards strengthening India’s development discourse through localised, ground-level understanding,” he said.

What began as a campus-based experiment is now turning into a small movement in Maharashtra. In August 2024, FLAME University hosted a national seminar titled Gazetteers: Past, Present and Future and signed an MoU with Maharashtra’s Gazetteer Department to pursue joint research.

Earlier that year, Goyal took the project to a wider audience at a TEDx event, speaking on colonial gazetteers and the representation of Indians as “dirty and dishonest” in a talk titled Colonial Gazetteers of India: Stereotyping a Nation.

Goyal’s endeavour has even grabbed the attention of national policy advisors. Sanjeev Sanyal, a member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (EAC-PM), praised not just the Moradabad project but Goyal’s efforts, noting how colonial administrators once took “a lot of trouble to document Indian districts in detail.”

To be fair to colonial-era administrators, they took a lot of trouble to document Indian districts in detail — their histories, cultures, statistics. This are still interesting to read. So, am happy that there is now an effort to revive this tradition. Recently saw one for…

— Sanjeev Sanyal (@sanjeevsanyal) December 7, 2025

Shamika Ravi, also a member of the EAC-PM, called such local data a “critical resource” for precision policy-making and said she hoped the model would scale beyond Maharashtra.

I remember discussing this idea with @yugank_goyal 3 years ago. Thrilled to see the outcome! As we move towards #PrecisionPolicymaking this type of local data becomes critical resource. Hope to see this scaled beyond districts of Maharashtra soon. Strongly recommend:… pic.twitter.com/2oxWvBYGVv

— Prof. Shamika Ravi (@ShamikaRavi) December 20, 2025

A way for British to establish control?

By the mid-19th century, the British administration had begun to see systematic documentation as essential to governing India. Out of this need emerged the gazetteer: a detailed geographic and administrative record of districts and provinces.

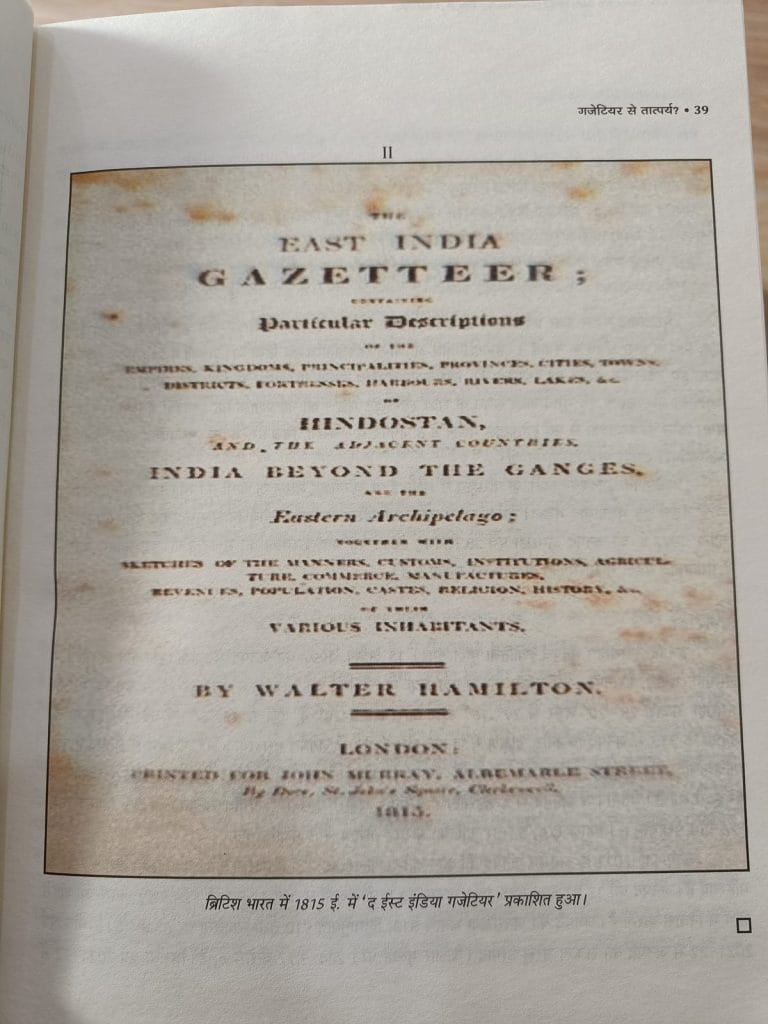

As far back as 1815, gazetteers were produced for smaller territories. Six decades later, historian and ICS officer WW Hunter formalised the process through the Imperial Gazetteer series.

For early colonial administrators, the task was daunting. They were dealing with unfamiliar languages, social systems, and landscapes, while attempting to establish their dominion.

PC Roy Chaudhary, who was the state editor of the Bihar district gazetteers in the 1960s, elucidated upon this.

“It was a very challenging task for them and they realised that they had to work through the local people. It is not that the British were always altruistic. They had to enforce new land laws, set-up educational institutions and overhaul the revenue and criminal administration… for this they had evolved the idea of compiling gazetteers for the districts and provinces and for the Indian empire,” he wrote in the IIC Quarterly in 1975.

The result was a set of records that functioned as essential administrative manuals and encyclopaedias of territory and people, detailing geography, resources, demography, economy, and trade.

Sanjeev Sanyal told ThePrint that gazetteers had by no means outlived their usefulness.

“The British gazetteers still help for references and to know the background for many issues. The British recorded their time and it’s important for us to record our time,” he said.

At the national level, former NITI Aayog member Bibek Debroy has also championed their value. In 2016, he described gazetteers as “a treasure trove of information,” arguing that while development is dynamic, district gazetteers offer a sense of legacy, as well as insights into why certain districts continue to stay “backward”.

Also Read: A Varanasi royal family vs British history. And one man’s war to decolonise the past

Bihar and the gazetteer challenge

If Moradabad shows what a revived gazetteer can achieve, other states illustrate how the exercise can unravel.

In 2020, the Rajasthan government announced plans to prepare gazetteers for all 33 districts, allocating Rs 5 lakh each for six districts in the first phase. Five years on, these have been completed for Hanumangarh, Karauli, Pratapgarh, Alwar, Jodhpur, and Banswada but there seems to be little progress elsewhere.

“After the announcement, there was no concentrated effort for this project. Initially we made some teams to make a new format for the gazetteer but work could not proceed,” said a senior revenue official of Rajasthan.

Another ongoing case in point is Bihar. After an unsuccessful pilot for the Darbhanga and Patna gazetteers, the Bihar government decided last year to commission gazetteers for seven districts in north Bihar: Purnea, Katihar, Araria, Kishanganj, Saharsa, Supaul, and Madhepura. In February, a notification was issued and the Delhi-based Institute for Human Development (IHD) was assigned the work, with Bihar’s land and revenue department as the nodal agency.

A team of around 36 researchers was deployed on the ground, with additional district magistrates appointed as nodal officers.

The state already had a track record of success. After Independence, Bihar began rewriting its gazetteers in 1952 and, in 18 years completed all 17 districts. The state last published district gazetteers in 1970, under the supervision of P C Roy Chaudhary. Other states started similar projects but were unable to complete them.

The team is not giving importance to archival records and just wants to copy-paste the British gazetteer. Even district officials are not giving detailed data

-Ramesh Kumar, former field researcher with the Bihar gazetteer team

“Bihar is the only state that completed all the 17 district gazetteers by 1970. Out of the 337 proposed district gazetteers only 134 have been so far published,” wrote Chaudhary in his article titled The Story of the Gazetteer.

This time around, though, there’ve been hitches.

The plan, said field researcher Ramesh Kumar, was to concentrate on three sources—administrative data, inputs from academics, and, in a more novel approach, oral histories about the temples, monuments, folktales, folklore, flood, festivals, dances, and caste.

But in his three months of doing field work in Supaul, Madhepura, and Saharsa, Kumar encountered stumbling blocks. British-era gazetteers had been built on a steady stream of departmental reports, published weekly and monthly, which no longer exist.

“These reports were the base for the gazetteers. After independence, these reports were not published and departments did not document their work properly,” said Kumar.

Representation was another fault line. Kumar said the IHD team spoke largely to men, excluding women, Muslims, and migrant workers. Entire social shifts were sidelined, according to him, such as Shiv Charcha, a religious movement among marginalised communities.

When Kumar travelled across the banks of Kosi to collect stories about flooding and migration, he noticed children collecting wood from the river and selling them at a local market to help make ends meet for their families.

“I wanted to include this type of social and cultural shift in the gazetteer. But they refused to give these priority,” he said.

In September, Kumar resigned from the project, accusing the team of adopting an unscientific approach.

“The team is not giving importance to archival records and just wants to copy-paste the British gazetteer. Even district officials are not giving detailed data,” he alleged. “How can we write a history of 50 years with data from just the last two or three years?”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)