Lakhisarai: The roof was leaking, the blackboard was broken, and students were sitting on the floor. It was Mukul Kumar’s first day as a teacher in a Bihar government school in Badhai block of Lakhisarai in 1994. Three decades later, the paint is fresh, a whiteboard gleams on the wall, and wooden desks fill the classroom. But the quality of education, Kumar claims, hasn’t changed.

Mukul Kumar’s journey from 1994 to 2025 tells Bihar’s larger story of stagnation, even as the Nitish Kumar government seeks to extend its two-decade rule. Reforms have changed the surface but not the system, whether in education or healthcare. The effects ripple through jobs, migration, and the state’s stubborn multidimensional poverty.

None of Kumar’s three sons studied in their hometown, Lakhisarai. All of them went to school in Patna, about 130 km away, and then moved to Delhi for college. He doesn’t want his children to come back as he does not see any future in Bihar.

“I studied in a government school but my children went to private schools. I wanted the best for my children so I sent them to Delhi. Bihar has a long way to go,” said Kumar, 61.

As Bihar heads to vote on 6 and 11 November, Kumar echoes what many in the state say. Progress can be seen, yet not always felt. Bihar has moved from absence — a lack of schools, primary health centres, roads — to presence with inadequate function.

Over the last two decades, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s government has transformed Bihar’s physical landscape with highways, bridges and electricity networks, and the darkness and isolation of the 1990s is gone. But this hasn’t translated much into economic progress or jobs. The contrast between the optics of ‘Vikas Raj’ and lived experience of governance is what defines the current poll mood.

Sitting on the verandah of his two-storey home, Mukul Kumar argues that some things are even worse than before, such as the quality of teachers. When recruitment shifted from the Bihar Public Service Commission (BPSC) to local panchayats, qualifications mattered less than connections, according to him. There is less accountability.

“The buildings are better, desks are there, but the quality of teachers has gone down,” he said. “In Lalu’s time, selection happened through BPSC. Under Nitish ji, it shifted to local sarpanch. That made the difference.”

Migration for education is a pattern Bihar’s people have been following over the past four decades now. And it has gotten worse in the last two decades. They have accepted it as their natural fate. Finish school, leave Bihar. If you can’t, then leave after college. But for a vast majority of the 2.65 crore migrants from Bihar, leaving is about surviving more than dreaming big. Because of low educational attainment and skills, most are trapped in low-paying jobs far from home and running their families back home on their meagre remittances, averaging just Rs 35,000 a year, as reported earlier by ThePrint.

Bihar’s governance model worked to expand the access for education and health services but it ignored accountability

-Sachin Sanjay, assistant professor of economics in Patna University

Between 2005 and 2025, Bihar’s per capita income rose from Rs 7,000 to nearly Rs 60,000, yet it remains India’s poorest state. It was India’s worst-performing state overall in NITI Aayog’s Sustainable Development Goals Index 2023-24. It ranked lowest in education and seventh-worst in health — the same positions it held in the 2021 index.

National Family Health Survey data from 2005 to 2021 show that Bihar has consistently ranked at or near the bottom on health and education indicators such as female school attendance and child malnutrition. In the UNDP Human Development Index 2022, it scored the lowest among Indian states.

There are recurring protests by teachers over delayed eligibility exams and shortfall of posts, and by health professionals over pay and safety.

“The government invested in infrastructure. They built schools, hospitals and opened health centres in villages but the quality is absent from there. Health and education were treated as employment sectors and that’s the reason why human resources weren’t converted into human capital,” said Sachin Sanjay, assistant professor of economics in Patna University. “We have better schools now but the quality of education the children are getting in government schools is poorer compared to 15 years ago.”

Also Read: ‘We build India, who will build Bihar?’—Chhath train is a migrant story of despair

What’s the education report card?

Thirty-nine-year-old Danapur shopkeeper Pushkar Paswan recalls walking 4 kilometres to school since there was only one for four villages. He had no textbooks or notebooks, instead carrying a slate and chalk in a bag stitched by his mother. He only studied till Class 7. His son doesn’t have to face such hardships.

“My son has been given notebooks and a school bag. He doesn’t have to walk this long. We have school in our village and he goes there with other kids,” said Paswan.

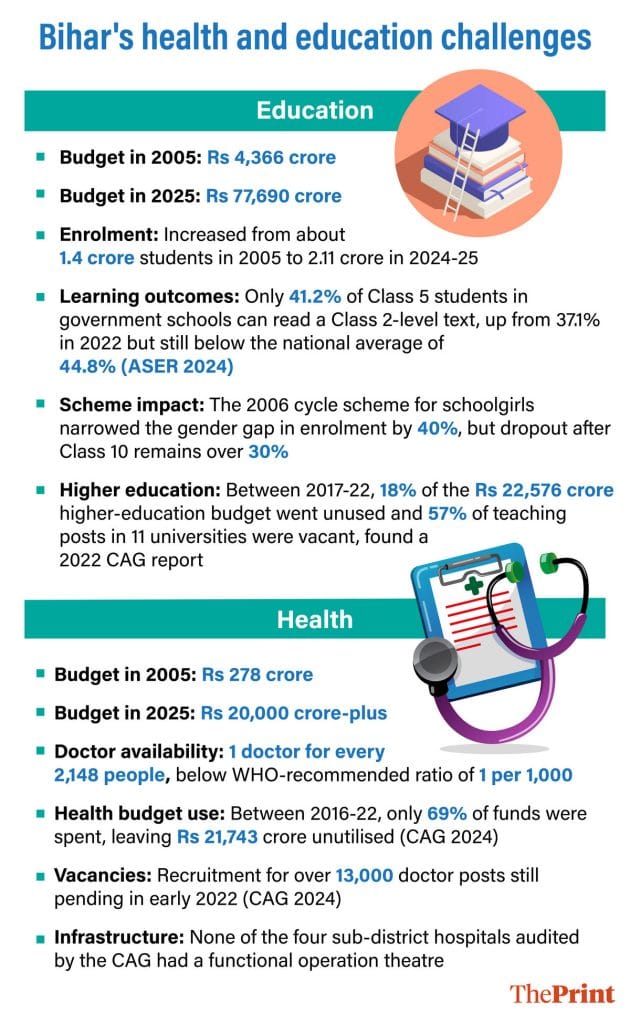

Under the Nitish Kumar government, there are now schools in almost every village. In the run-up to the polls, the government has been tom-tomming its achievements. In August, Nitish posted on X that Bihar’s education budget in 2005 was Rs 4,366 crore, which has risen almost 18-fold to Rs 77,690 crore in 2025.

Total school enrolments grew from about 1.4 crore in 2005 to 2.11 crore in 2024-25. Yet the central government’s latest UDISE+ report shows Bihar saw the steepest fall in government-school enrolments in 2023-24, down 28.9 lakh — a decline officials told ThePrint was because of families re-migrating after their pandemic return to Bihar.

Kumar recounts that he felt “devastated” in his early years as a teacher in the 1990s. The government was essentially absent, teachers were MIA, and students had no resources. “I remember teachers just coming to school, spending one hour and going back to their homes. It was the smartest students who used to handle the class till then.”

When Nitish became CM, he admitted there were some meaningful changes: “Students got a dress scholarship from the government, which increased the enrollment in Bihar.”

Another famous programme, launched in 2006, was giving bicycles to school girls. It was even replicated by countries such as Zambia. A detailed 2016 study found that it narrowed the pre-existing gender gap in enrollment by 40 per cent, with the biggest gains in villages more than 3 km from a secondary school.

The buildings are better, desks are there, but the quality of teachers has gone down. In Lalu’s time, selection happened through BPSC. Under Nitish ji, it shifted to local sarpanch. That made the difference

Mukul Kumar, teacher

Two decades after the scheme’s launch, the question is what happened to those girls. The dropout rate after Class 10 in Bihar remains over 30 per cent (UDISE+ 2021–22). Only 14 per cent of girls aged 18-23 are enrolled in higher education, one of the lowest rates in India (AISHE 2022).

“The cycle scheme became the global recognition for Bihar at that time but two decades later we don’t see a rise in girls getting jobs or to higher education,” said Sachin Sanjay.

In his classroom at Patna University, he has noticed a dip in students’ awareness and learning levels over the years.

“Now the students who are coming to us after completing school aren’t fully developed; they lack knowledge if we compare them to students 15 years ago. That shows that the infrastructure didn’t upgrade the quality of education. It has gotten worse,” he said.

The ASER 2024 report shows some improvement but continued challenges for Bihar: only about 41.2 per cent of Class 5 students in government schools can read a Class 2-level text— it’s an improvement from the 37.1 per cent in 2022 but well below the national average of 44.8 per cent. For arithmetic, 28.2 per cent of Class 3 students in Bihar can solve simple subtraction problems, while the national average is 33.7 per cent.

There are also substantial digital gaps. Only about 25 per cent of all schools in Bihar have computer facilities, compared to the nationwide 64.7 per cent.

On the higher education front, a CAG report tabled in the Bihar Assembly in March said between 2017 and 2022, 18 per cent of the Rs 22,576 crore budget was not used, pointing to “unrealistic budget proposals and inadequate financial control mechanisms”. It also found that 57 per cent of teaching posts in 11 test-checked universities were vacant.

Some reforms have also exacerbated problems. One of the weakest links in Bihar’s education trajectory is the new system of appointing teachers.

In the mid-2000s, the Nitish government replaced the BPSC-based teacher recruitment with panchayat-level hiring under the Niyojit Shikshak scheme. It filled vacancies more rapidly but some say it diluted accountability and quality.

“We studied for the exam, we got recruited by a process, and have the qualifications but through the Niyojit process many people who didn’t even know the basics got into the system and that affected the quality of education,” alleged Kumar.

A May 2025 paper published in the peer-reviewed Research Review International Multidisciplinary Research Journal noted the gap between policy intentions and classroom realities runs deep. And that disadvantaged groups bear the brunt of it.

“Marginalised groups disproportionately occupy lower-quality schools, with weaker infrastructure, fewer trained teachers and limited resources, thereby perpetuating existing inequalities,” the study said.

It’s much the same story for the health system.

Also Read: Bihar has many Khushboo Kumaris who score 400 but don’t get to study science. Arts their fate

Healthcare—high budget, low returns

In Lakhniviha village near Danapur, the primary health centre stands locked behind rusting gates. The board outside lists opening hours, but there’s no one there.

Fifty-six-year-old farmer Rambhajan Kumar, who had a high fever a few weeks ago, went there first but finding it closed, he had to go to a private clinic. He was diagnosed with typhoid and was forced to pay Rs 1,200 that he could ill afford. Most other villagers don’t bother to stop by at all.

Sarpanch Chandan Kumar suggested it was a chicken-and-egg problem: the government health centre stays shut because no one trusts it, and no one trusts it because it’s always shut.

“I had asked them to open it a few days ago. The nurse there also complained, saying, ‘You’ve put me back here, but what do I do when no one comes?’ So when it closed again, I didn’t do anything. People do not go there. They go to private hospitals,” said the sarpanch.

The same story repeats itself higher up the chain. Bhagwan Mahavir Institute of Medical Sciences (VIMS), Lakhisarai’s largest hospital, often seems bereft of doctors.

“If you don’t have a recommendation or connection, you won’t get proper treatment,” said 30-year-old technician Kundar Kumar, who has worked there for nine years. “If there are supposed to be seven doctors, you’ll find only one, and not a senior one. This is the new Bihar.”

But 69-year-old Ram Swarth Singh, a compounder for 35 years in Lakhisarai, recalls when the situation was even more dire. Back in the 1990s, he was the de facto doctor for many villagers. There were no hospitals nearby and people had to travel to Patna even for the minor procedures.

Doctors write prescriptions for medicines that you can only find in one private shop nearby. There are also agents outside who tell serious patients to go to a private hospital. They get Rs 500 for every patient they take there

– Ram Swarth Singh, former compounder

“The government didn’t post that many doctors at that time and even doctors didn’t want to work in Bihar. The doctors used to come only for high-profile cases,” said Singh.

Over the last couple of decades, the government has increased spending and has been on a recruitment drive for doctors. However, the same legacy problems are far from erased.

From Rs 278 crore in 2005, the state’s health budget has reached over Rs 20,000 crore in 2025, with 6.6 per cent of total expenditure allocated to health — above the 6.2 per cent average allocation by states.

But a 2024 CAG report showed that between 2016-17 and 2021-22, Bihar spent only 69 per cent of its health budget, leaving Rs 21,743 crore unutilised. Recruitment for over 13,000 posts was still pending in early 2022, and none of the four sub-district hospitals audited had a functional operation theatre.

The state has only one doctor available per 2,148 people, far below the WHO-recommended one per 1,000. The first line of treatment is failing in many villages of Bihar.

“To improve the health infrastructure, we need to strengthen the first line of treatment at the village level. Cases that can be managed at the PHC level end up at the district hospital, increasing the load there. Most of these PHCs are run only by ASHA workers,” said Sanjay.

Also Read: The story of Bihar’s two mafias—sand and booze

The hidden costs

Scam after scam has shaken Bihar’s education and health systems over the years: teacher recruitment scam, paper leak scam, uterus-removal scam, ‘kidney kaand’, and now, an alleged ambulance scam that has become a hot-button issue this election.

But beyond these headline-grabbing cases is the petty, routine corruption that most people in Bihar have almost come to expect.

In December 2024, a school principal was caught on camera taking eggs meant for mid-day meals out of a delivery van. A probe confirmed misuse of food supplies, and local outrage forced an inquiry.

“Taking away the food from children is a classic example of corruption and this is where it starts, it has a long chain of supply. The food disappeared before it could reach children,” said Mukul Kumar, adding that such diversions are common across blocks.

Teachers say they often pay bribes to officials just to get their dues cleared. In April this year, a clerk at the district education office in Patna was caught accepting Rs 15,000 from a teacher seeking to fast-track his salary arrears.

“The teacher was told by officials that he will have to give 15 per cent of the total arrears. His salary amount was Rs 5.5 lakh. He had initially been told the commission would be Rs 82,000 but they settled on Rs 15,000,” said Nirmal Anand, a teacher in a senior secondary school of Patna told ThePrint.

Earlier this year, the state’s education department fined over 5,100 headmasters for irregularities in the Mid-Day Meal Scheme — worth Rs 10.87 crore. Five months later, most hadn’t paid up.

“Who follows the orders here? Everyone is corrupt, from teachers to officials to leaders. You can just give a bribe and get away with it,” said a Patna-based teacher who asked not to be named.

The affliction extends to healthcare. At the government health centre in Barh block of Patna district, patients alleged that promised free medicines were never available.

“Doctors write prescriptions for medicines that you can only find in one private shop nearby,” said Ram Swarth Singh, who visits the centre every month to fill his prescription. “There are also agents outside who tell serious patients to go to a private hospital. They get Rs 500 for every patient they take there.”

From forged attendance sheets in schools to fake billing in PHCs, petty corruption is the thread that runs through Bihar’s development story.

“Bihar’s governance model worked to expand the access for education and health services but it ignored accountability,” said Sachin Sanjay.

At Pawapuri village in Nalanda district, a group of villagers resting under the shade of a tree came to the consensus that the more things changed, the more they remained the same in Bihar.

“It was all Jungle Raj in Lalu’s time but now Modi ji is talking about Vikas Raj. Let’s see if that can actually happen in Bihar,” said farmer Sohan Lal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

In Karnataka, not only roads, but also classrooms and clinics have huge cracks.