Agra: Wine businessman Balakrishna Anand travelled 2,000 kilometres from Chennai to Agra chasing an audacious dream. He wanted to turn local kinnows into premium wine. One taste, and he knew he’d struck orange gold. It’s the latest chapter in Agra’s blossoming love story with the citrus fruit.

“While navigating through the lush orchards, I found the best quality of kinnows. Agra is a completely new market for us but we were not disappointed at all after coming here. We got the kind of goods we wanted here. Kinnows can be Agra’s next big thing,” said Anand. He bought 10,000 quintals from the district’s farmers in December to process them into citrusy wine at his Chennai factory. He plans to market it domestically in March under the brand name Anand Wines.

Until now, Agra’s kinnows mostly went to local fruit markets or juice stalls and rarely made it beyond Uttar Pradesh. But the fruit’s popularity has steadily risen over the past decade.

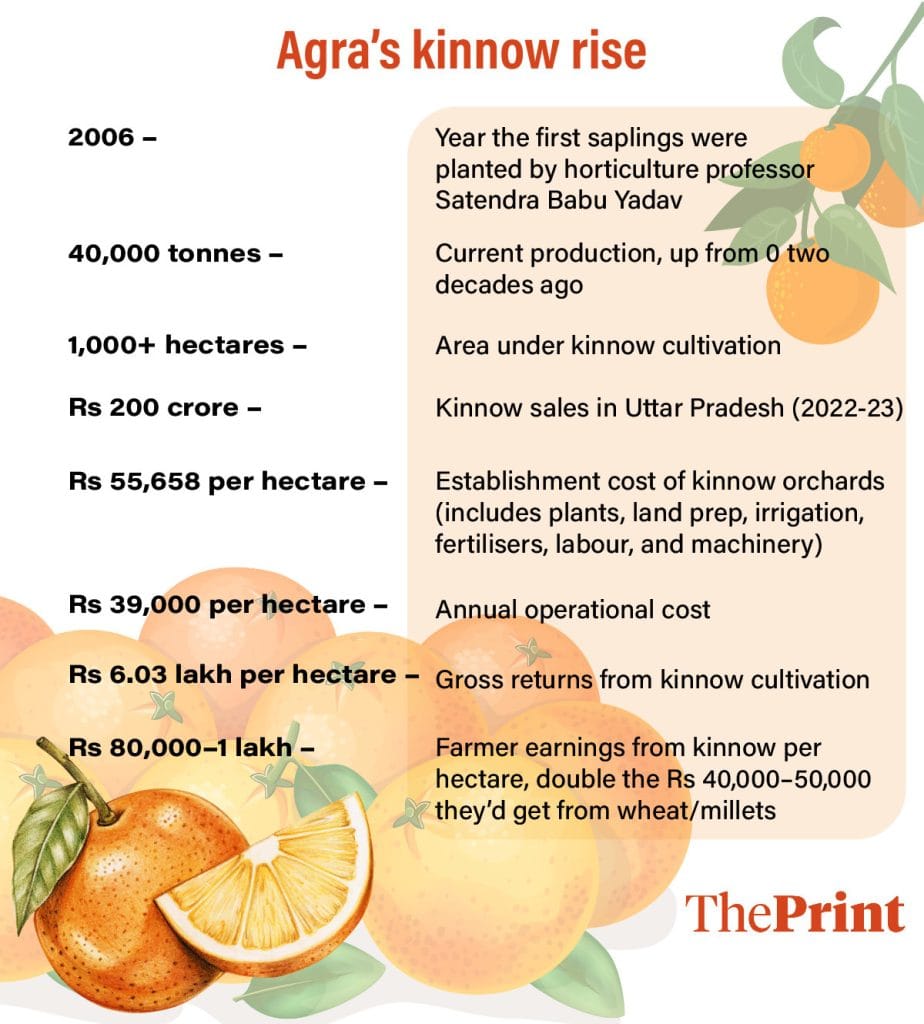

Agra, traditionally famous for potatoes and petha, is quietly emerging as a new kinnow hub and challenging the dominance of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Haryana. The fruit wasn’t even cultivated here until 2006, but since then, production has expanded rapidly. Today, Agra produces around 4 lakh quintals (40,000 tonnes) annually. In 2022-23, kinnow sales in Uttar Pradesh reportedly reached Rs 200 crore, with Agra accounting for the bulk of it.

“It has grown to over 1,000 hectares in the last 15 years. It has become quite popular in the last 10 years. Farmers are seeing more profit in this crop,” said DP Yadav, deputy director, horticulture, Agra.

Farmers who once earned Rs 40,000-50,000 per hectare from wheat and millet now make twice as much from kinnows. While Punjab—the ‘mini California’ of kinnows—is seeing a weakening market, with many farmers switching to other fruits and crops, Agra’s cultivation is steadily rising.

Earlier, we only bought kinnows from Punjab and Haryana. But we took the risk of buying from Agra and did not incur any loss. Agra kinnows are making a mark and their market reach is also increasing

-Sanjeev Kumar, a fruit trader at Azadpur mandi

The transformation began when Satendra Babu Yadav, professor of horticulture at Uttar Pradesh Rajarshi Tandon Open University (UPTROU), challenged conventional wisdom.

“People thought kinnow could never grow here, but we proved them wrong,” said 59-year-old Yadav.

Farmers now call him the “Kinnow Man of Agra”.

Now, kinnow orchards stretch for kilometres along the fertile banks of the Yamuna river, spreading into neighbouring districts such as Firozabad and Kasganj. Until Yadav’s intervention, kinnow farming was considered impossible here.

“We have proved that kinnow is not limited only to a few states such as Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan. Apart from Taj Mahal, potato, and petha, Agra’s identity has now started getting associated with kinnows as well,” said Yadav.

But it took over a decade for this identity to be formed.

On a warm, sunny January afternoon in Hingot Kheria, near the Agra-Lucknow Expressway, Yadav strolled through his orchard. Once an experiment in kinnow cultivation, is now a showcase of fruits and vegetables, where he’s also trying to coax pomegranates from the soil. He gestured to the garden caretaker to pluck a dark orange kinnow and then peeled it with a flourish.

“The peel of the kinnow is very soft here, which makes it special, and its sweetness is also quite high. Compared to other regions, it is less fibrous,” he said proudly.

As a cash crop, kinnow is is boosting farmers’ incomes and reaching mandis across the country, he pointed out. The arrival of winemakers like Anand has opened up new markets for Agra’s kinnows.

“If more wine traders come, farmers will get even better prices. A big boost was overdue for kinnow farming,” he said.

Jitendra, a farmer from Barauli Ahir block, said he too has seen the transformation firsthand.

“Seeing double the profits, new people are now attracted toward farming. This crop guarantees no loss,” he said.

This year, Agra farmers received Rs 18–20 per kg for their kinnow crop, substantially higher than the Rs 10-12 per kg they got in the early years.

Also Read: India’s agriculture education stuck in Green Revolution mindset

Agra’s kinnow gambit

When Satendra Yadav visited Punjab in 2005 on a family trip, he had no idea he was about to put Agra on India’s citrus map. At the time, Uttar Pradesh had zero kinnow production. But a visit to a sprawling orchard in Abohar changed everything.

“It was a pleasant feeling to see the big gardens of kinnow spreading across several bighas in Punjab. The kinnows on the tree fascinated me. I decided to do something similar in Agra and brought hundreds of saplings from there,” said Yadav, speaking animatedly as he recalled that moment. He remembers every detail, from planting his first sapling to the exact name of the official posted in Agra 15 years ago.

When he returned home with the saplings, Yadav’s first move was to plant them in his own garden so that farmers could see for themselves it could be done.

“No one had ever tried this, so I had to change their mindset,” Yadav said.

His next challenge was convincing local farmers, who had grown potatoes and wheat for generations, to take a chance on kinnow. His wife, then block pramukh (head) of Barauli Ahir in Agra, helped him tap into the area’s plantation funds. But there was fierce resistance at first.

In meetings, farmers often asked whether planting kinnow would increase income. My answer was that their income would double

-Satendra Babu Yadav, horticulture professor

“Shifting them to the new crop was nothing less than impossible. We tried to convince them that they can grow potatoes and kinnow simultaneously in the same field,” said Yadav.

To get them onboard, Yadav held small meetings in villages with support from the Horticulture Department and local Block Development Officers. Many were still wary, so he sweetened the deal—free plants, plus a promise of higher profits.

“In meetings, farmers often asked whether planting kinnow would increase income. My answer was that their income would double,” said Yadav.

That got their attention. After five months of persuasion, around 1 lakh kinnow saplings were planted by more than 100 farmers across Barauli Ahir block in 2006.

“No one looked back after that,” said Yadav, gesturing at the trees stretching across hundreds of acres. Most of the fruit had already been plucked, with only a few kinnows still clinging to the upper branches.

Word slowly started spreading.

“When farmers began seeing profits from kinnow, they told their relatives in nearby districts. Soon, the crop expanded there too,” said Yadav.

Farmers, however, weren’t the only reluctant converts to kinnow. District officials resisted the idea as well.

When the government’s National Horticulture Mission (NHM) was launched in 2005-06, providing subsidies for horticultural crops, Yadav pushed to get kinnow included. But first, he needed the approval of Agra’s District Magistrate, who shot down the idea immediately.

“When the DM saw the file, he said kinnow couldn’t be grown here. He scolded all the officials and refused to sign,” Yadav recalled. “Then I gave him the example of my garden and he agreed— the crop was included in the mission.”

Punjab’s Fazilka, Ferozepur, Muktsar, Bathinda, Faridkot, and Mansa districts form the ‘kinnow belt’, accounting for 75 per cent of Punjab’s orchards and 70 per cent of the country’s total output.

Punjab losing zest, Agra gaining ground

For decades, kinnow has reigned as Punjab’s ‘king fruit’, with 47,000 hectares under cultivation. But with profits shrinking and orchards withering, many farmers are pulling the plug, even as the vitamin C-packed citrus takes off in Agra.

“Punjab where Kinnow is traditionally grown from the 1950s, the plants are now declining and productivity is decreasing,” said AK Dubey, a scientist at ICAR- Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Delhi.

A hybrid between King and Willow Leaf mandarins, kinnow was first introduced to Punjab by JC Bakshi at Punjab Agricultural University’s research station in Abohar in 1954. In Punjab, harvesting runs from November to February, while in UP, it’s from December to February. According to National Horticulture Board data, kinnow and mandarin plantations cover 4,29,290 hectares across India, yielding 47,53,830 metric tonnes.

Punjab’s Fazilka, Ferozepur, Muktsar, Bathinda, Faridkot, and Mansa districts form the ‘kinnow belt’, accounting for 75 per cent of Punjab’s orchards and 70 per cent of the country’s total output. Haryana and Rajasthan come second and third, producing 5.25 lakh metric tonnes and 3.5 lakh metric tonnes, respectively as of 2023. Uttar Pradesh ranks a distant fourth with approximately 50,000 metric tonnes.

The hot, dry climate in southwest Punjab and Rajasthan has long made them ideal for kinnow cultivation.

“Its production thrives in regions with low rainfall and high sunshine hours,” said Dubey, adding that this fruit never yielded in the Agra region before.

Punjab where Kinnow is traditionally grown from the 1950s, the plants are now declining and productivity is decreasing

-AK Dubey, a scientist at ICAR- Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Delhi

Climate shifts, however, are changing the equation, and areas once deemed unsuitable—like Agra and even Bundelkhand—are now showing potential, according to him.

Meanwhile in Punjab, farmers’ relationship with kinnow is souring.

In 2023-24, orchardists in Abohar and Fazilka reported losing 20-50 per cent of fruit-bearing trees, blaming contaminated water, erratic canal supply, pest attacks, and ageing orchards. Last year, over 1,000 acres of kinnow trees in Fazilka were cut down to make way for paddy. In Rajasthan’s Sriganganagar, too many farmers have reportedly uprooted kinnow trees in the last couple of years, citing unfavourable climatic conditions, irrigation issues, and low yields.

“Kinnow is not as profitable as it used to be. Even after a bumper crop, we are not getting a good price,” said Gurpreet Singh, a kinnow grower in Fazilka, who uprooted some of his orchards to cultivate paddy.

Despite these challenges, reports suggest an uptick in prices. Wholesale rates depend on fruit quality, and as of January this year, kinnow was selling for Rs 20-25 per kg in Punjab, up from just Rs 10-12 per kg last year.

But a new issue has cropped up. Bangladesh, a key kinnow importer—along with countries like UAE, Iran, Kuwait, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore— increased customs duty from Rs 33 to Rs 98 per kg, leading to a significant drop in exports.

“It caused a setback to the farmers and exporters of Punjab,” said a state horticulture official.

Agra’s story is heading in the opposite direction.

It’s still far behind Punjab and Rajasthan in absolute production, but its orchards—planted near the nutrient-rich Yamuna floodplains—are producing high-quality fruit and proving that kinnow can thrive in Uttar Pradesh. Unlike Punjab’s export-heavy focus, Agra is catering entirely to the domestic market, with relatively young orchards producing better-quality fruit.

When Chennai’s Balakrishna Anand was looking for the perfect kinnows for his wine, he was all set to strike a deal with Punjab farmers. But before flying out from Delhi, he decided to stop in Agra. It was enough for him to change his plan.

He was impressed with both the fruit’s quality and the logistics—while Fazilka is an eight-hour drive from Delhi, Agra is just two hours away.

“I found the best taste and travel option here,” he said.

Also Read: These are the Bengaluru startups bringing AI and farmers together

Agra kinnow farmers cashing in

Kinnow is adding juice to Agra’s farming economy, with more than 1,000 farmers now growing the crop. Many say they earn between Rs 80,000–1 lakh per hectare, which is about twice what they once made growing wheat and millet.

Jitendra, a farmer from Barauli Ahir, planted his first kinnow trees in 2010, encouraged by his neighbours’ success.

“The profit of Rs 40,000-50,000 we got for wheat and millet doubled with kinnow,” he said. Now he grows kinnow in 12 bighas (8.12 hectares) and has earned about Rs 6 lakh this season.

The fruit, he added, is also less vulnerable to waterlogging than traditional crops.

This year, Agra farmers received Rs 18–20 per kg for their kinnow crop, substantially higher than the Rs 10-12 per kg they got in the early years.

“After Covid, the demand for citrus fruits increased as it has high immunity-boosting properties, so now farmers are in the situation to negotiate for their crop,” Yadav said.

His research shows that the average yield is 88.4 kg per plant, with a per-hectare output of 294 quintals. The price per quintal was Rs 2,000 in 2022.

In the initial years, Agra farmers struggled with market access, but that has changed.

“We contacted the mandis in Delhi and started sending kinnows there. As people came to know about Agra kinnows through the mandi, traders themselves began to arrive,” said Yadav. Now, traders from Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow visit Agra’s orchards as early as May-June, making advance bookings while the kinnows are still small.

Most of Agra’s kinnow harvest goes to Azadpur Mandi in Delhi. But until a few years ago, fruit sellers there hadn’t even heard of Agra kinnows.

“Earlier, we only bought kinnows from Punjab and Haryana. But we took the risk of buying from Agra and did not incur any loss. Agra kinnows are making a mark and their market reach is also increasing,” said Sanjeev Kumar, a fruit trader at Azadpur mandi.

Agra’s kinnow plants still come from the Abohar region of Punjab, but local nurseries have now started buying and reselling saplings. Demand is rising yearly, said Omveer Singh, who runs a nursery that sees buyers for kinnow plants from Bareilly, Kanpur, Jhansi, and even Gwalior.

In October 2024, Yadav published a research paper titled ‘Impact of Kinnow Production on the Socio-economic Conditions of Farmers in the Agra Region’. He studied the lives of 100 farmers from 10 Agra villages, detailing their journey to profitability.

“Kinnow production is a viable and profitable agricultural enterprise that can contribute to both economic growth and social development in the region,” reads the paper.

But patience is key. Kinnow trees take two to three years to start bearing fruit, but returns far outpace the investment. Establishing a kinnow orchard costs Rs 55,658 per hectare and annual operational costs are around Rs 39,000 per hectare, but it’s a fraction of the Rs 6.03 lakh per hectare profit, according to Yadav.

“There is a lot of trust among traders about kinnow. So, farmers take advance money from traders in the name of kinnow crop and that money is paid back managed at the time of harvest,” he said. Yadav recalled visiting farmers in a village who happily told him they no longer faced a shortage of money because of kinnow.

But the true impact of Agra’s kinnow boom hit Yadav last year on a drive back from Noida. Stopping near Pari Chowk, he noticed a vendor selling kinnows from a cart. Curious, he asked where the fruit was from.

“These are kinnows from Agra,” the seller replied.

A smile spread across Yadav’s face as he recounted the moment: “I had been waiting a long time to see Agra’s kinnow being sold on the streets.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)