Bengaluru: Across the world, the predominant image of ISKCON members is one of merry singing and dancing to Hare Krishna chants on the streets. For Madhu Pandit Dasa, the chairman of ISKCON Bangalore, it has been just the opposite. His last 25 years have been a bitter fight in courts — for legitimacy and for brand image.

He has spent most of that time far from his ornate prayer hall, wading through litigation and trying to keep his reputation intact.

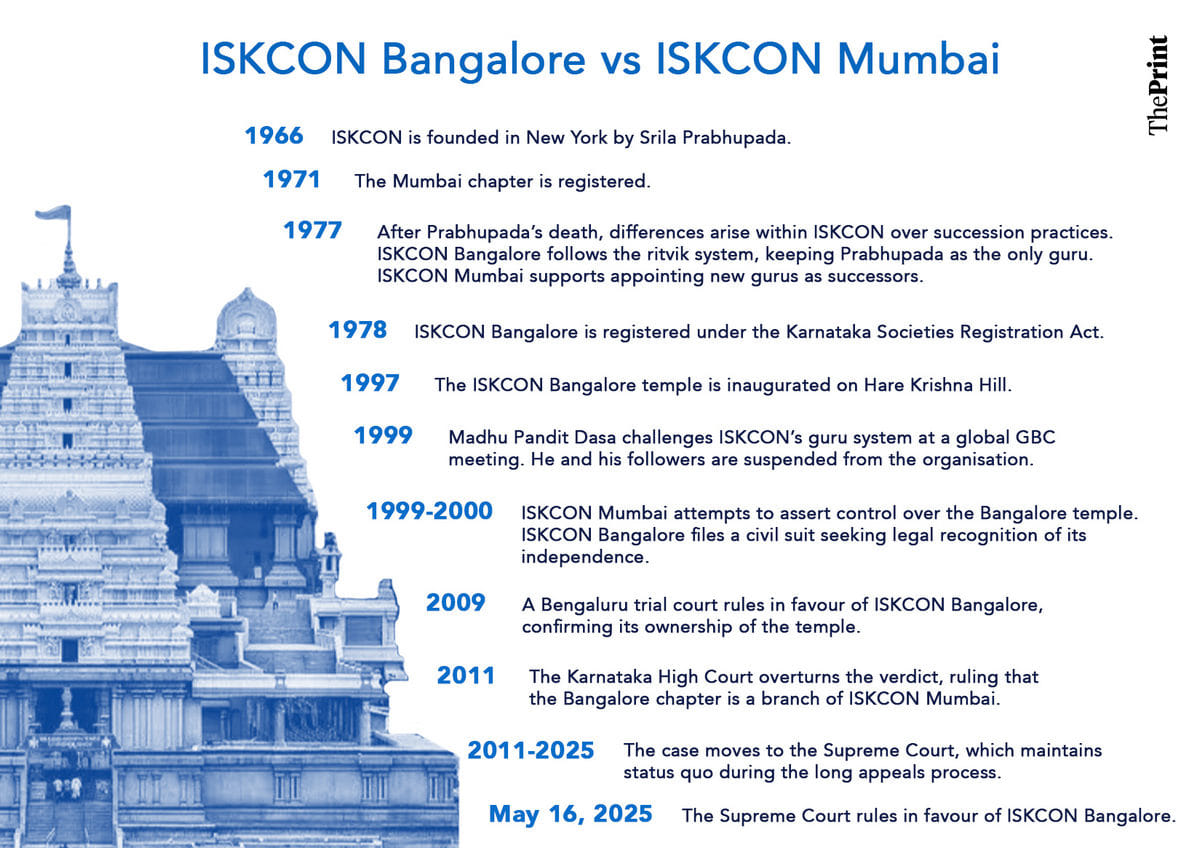

What began in 2000 as a petition by Dasa to assert ISKCON Bangalore’s independence from the Mumbai headquarters snowballed into a messy decades-long dispute—over the real estate on which the temple sits, theological differences, and factional vendettas. Last month, the Supreme Court finally set the record straight, declaring ISKCON Bangalore an independent entity. A previous High Court finding that ISKCON Mumbai was the owner of the Bangalore Hare Krishna temple was “completely erroneous”, the court said.

Seated cross-legged in his office behind a desk stacked with papers, Dasa declared that, on average, he’s spent 25 per cent of the last 25 years dealing with the court case, which pitted the Mumbai and Bangalore ISKCON chapters against each other. The rest of his time was spent working feverishly to expand the brand—partly a deviation tactic against the barrage of negative PR that was coming his way from some quarters of ISKCON, short for the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.

Dasa can now breathe a sigh of relief. Except for a tiny grouse. He’s unable to process the enormity of what he’s achieved.

To the unacquainted, it looked like a land dispute brought on by a mundane tussle for power. But for Dasa, what was at stake was the raison d’etre of ISKCON itself. When he questioned the new system of governance instituted after founder Prabhupada’s death, he was thrown out of the organisation. He was called a heretic and a renegade. He was no longer considered a true-blue Hare Krishna.

Following the 16 May verdict, his band of “heretics” was allowed back into the fold. The global ISKCON Governing Body Commission (GBC) even sent him a thank-you message and signalled their openness to his “peace proposal”. But inching their way back in was no mean feat — it required daily negotiations, calculations, and stretching the religious movement to function like a brand without losing its soul.

ThePrint e-mailed and sent WhatsApp messages to ISKCON Mumbai. This report will be updated if a response is received.

“The actual dispute is about succession. They misrepresented to the world continuously that I was fighting to take away the property. The theological aspect of the fight did not go out [to the public],” said Dasa. “But the fact is, why did it snowball into a property dispute?”

The battle was like any other corporate matter. It wasn’t about temple or faith. They went to war with the kinds of tools that are taught in business schools.

Both camps hired top lawyers and spent crores on legal fees. Dasa formed his very own legal team of “missionaries”, holding weekly strategy meetings. Meanwhile, allegations flew. He and his family were accused of misappropriating funds. Rumours swirled that the temple was just a front for Dasa to amass personal wealth. There were multiple brands that he needed to manage—the personal, the professional, and the public.

“It wasn’t good for our organisation. Our identities are different but the objectives are the same,” he said of ISKCON.

For IIT Bombay graduate Madhu Pandit Dasa, the legal war was just one front. He’s also on a crusade to build a more expansive, independent future for ISKCON.

Also Read: Osho land feud is a battle for legacy. Rebel swamis, court cases, Bollywood factor

Spirituality with start-up energy

Strategising took up a lot of time at ISKCON Bangalore.

“They were always ready to attack and spin a story. We had to counter those narratives,” said Chanchalapathi Dasa, senior vice-president of the society and Madhu Pandit Dasa’s brother-in-law. “It was a struggle for truth.”

What helped was that Dasa runs the Bangalore chapter like a buzzy start-up. There’s a heady focus on outreach and marketing, and brand value is the ultimate virtue. The high-stakes legal battle, and the deeper question of legitimacy underlying it, spurred them into constant expansion mode. From a single Hare Krishna temple in 1997, they’re now the proprietors of 52 temples across the world, and have their very own international chapter. Youth engagement became a key pillar though FOLK (Friends of Lord Krishna), pitched as a rest-house to “save” children from modern chaos. Dasa is also the founder of the Akshaya Patra Foundation, which provides mid-day meals at government schools.

The entire operation seems to be driven by two seemingly contradictory energies: spirituality and entrepreneurship.

As the fracas in court gained steam, Dasa was forced to reorient, left with no choice but to accept his new identity as an outlier. And now that the court has ruled in his favour, he can further energise what already appears to be a well-oiled machine.

On Bangalore’s Hare Krishna Hill, women in kanjeevarams trek up through rain, trailed by husbands and children. It’s more than a pilgrimage. The temple, with its airy spaces, play area and restaurant selling birthday cakes, now doubles as a tourist attraction. A Google search for ‘things to do in Bangalore’ brings it up as one of the top results.

Retaining my image was a big challenge for me. I needed to prove that I wasn’t just sitting and running a temple

-Madhu Pandit Dasa

Founded in 1966 and loosely overseen by the GBC, ISKCON today is effectively a spiritual franchise. With over 500 temples across the globe and new, technically unofficial ones sprouting up, the movement is now too fragmented to pin down. However, the Mumbai chapter has been the de facto power centre. Even the Kolkata chapter had come under its management before the Bangalore standoff

At the temple, though, the atmosphere of beatific calm remains untouched.

“I’ve never heard of any court case. I’ve just come to see the temple with my family,” said a local visitor, waiting outside the complex to retrieve his shoes.

Image wars and kitchen battles

It’s been a long time since Madhu Pandit Dasa filed that first petition demanding parity. But even now, he insists the other side threw the first punch.

“I went to the GBC and they expelled me. I had to defend myself. They attacked me first,” he said.

But even as the case dragged on, Dasa says he was always confident things would end in his favour.

“I never had any apprehensions. Property-wise, it’s a simple dispute. That’s why we had interim orders in our favour,” he said. “They could never step foot inside ISKCON Bangalore.”

But to some, it looked like a power grab — a move to wrest the temple from its Mumbai roots. Set up by Prabhupada, the Mumbai temple is widely seen as the apex organisation. Dasa scoffs at the idea. If it’s really about who came first, he points out, the original ISKCON is actually in New York.

“Who used the name first?” is a layered question with an even more multi-pronged answer.

Do not centralise anything. Each temple must remain independent and self-sufficient. That was my plan from the very beginning, why are you thinking otherwise?

-ISKCON founder Prabhupada in a 1972 letter

Court documents bring out some of the personal dynamics at play. It was submitted by ISKCON Mumbai’s counsel that four of the seven members on the Bangalore chapter’s governing body are Dasa’s family members, while the other three are “close friends”. One ominous submission says: “ISKCON Bangalore is the real alter ego of Madhu Pandit.”

Meanwhile, blogs like IskconTruth ran headlines like “Prabhupadanugas against Madhu Pandit Dasa: Truth Revealed”. While Dasa frequently features in listicles about “IIT-ians turned monks”, the case has cast a shadow on his image. In a 2012 interview, headlined ‘ISKCON Bangalore comes clean’, he accuses the Mumbai chapter of orchestrating allegations about Akshaya Patra. Another article last year, titled ‘The Lord Have Mercy’, avows, “ISKCON’s image is in the dumps, the scrap over Bangalore centre’s assets is one more nail.”

Through all the negative press, Dasa kept things tight. The dispute was handled on a need-to-know basis. Even his supporters weren’t fully in the loop. Instead, he assembled six “missionaries” — his makeshift legal team— and held weekly meetings.

The court drama had practical, logistical consequences too. A blanket ban barred ISKCON Bangalore devotees from staying at Mumbai’s guesthouse, which had once been open to all. The Bangalore faction had to construct its own lodgings. The dispute seeped into every operational crack.

Even Akshaya Patra — the initiative that’s earned Dasa the most goodwill— hasn’t emerged unscathed. Described by him as the “world’s largest NGO”, this partnership between ISKCON Bangalore, the government’s midday meal scheme, and a slew of donors has fielded several accusations.

According to Dasa, about a decade ago, ISKCON Mumbai began spreading stories in political circles. Soon after, a question was raised in the state assembly asking for Akshaya Patra’s financial records to be made public.

Accusations abounded — that Dasa had siphoned money and grown wealthy off the midday meal scheme. Dasa retaliated through a press conference where he set the record straight regarding their finances.

“I was happy to do the press conference. Our books, our stocks, everything is out in the open,” he recalled. “There is not a single grain of rice that is unaccounted for.”

Between government funding and private donations, Akshaya Patra has received around Rs 750 crore so far. It’s branded as a “secular” organisation and the ISKCON name stays in the background. But it gives Dasa public credibility that even his adversaries cannot sully.

“Retaining my image was a big challenge for me. I needed to prove that I wasn’t just sitting and running a temple,” he said.

Dasa is also keen to shake the perception of ‘Hare Krishnas’ as elitist, and claims to have made headway in that direction.

“In these 25 years, ISKCON Bangalore has contributed a lot to building the brand all over India,” he said. “Otherwise, it was always known as a rich people’s organisation. People used to ask, ‘What are they doing for common people?’”

Their proclivity for the bright and shiny, Dasa says, isn’t personal. It’s a reading of the public mood, one that traces back to the late Prabhupada.

A ‘Vatican’ in Vrindavan

Aspirational grandeur has become an elemental part of the brand. The ceiling of the Bengaluru temple has Renaissance-style paintings of Krishna. The shrine itself is a startling house of gold.

In Dasa’s office sits a model of their second temple: a large, bejewelled white-and-gold structure, rimmed with more gold. This gargantuan project in Vrindavan is set to become the tallest religious structure in the world. Their proclivity for the bright and shiny, Dasa says, isn’t personal. It’s a reading of the public mood, one that traces back to the late Prabhupada.

After building the Mumbai temple, the founder was once asked by a journalist: why do you spend so much money?

“The year was 1977. India was not what it is today. But he gave a beautiful answer—’If I sit in a hut, no one will come see me’,” said Dasa.

Creating “glittering temples” to build cultural memory is something all religions do, according to him.

“I have to create iconic structures. That’s how people will get attracted. Architecture is key to the survival of religion,” he said. “Today, the Vatican is a symbol of Catholic faith.”

The quest to build something eternal is always top of mind. And it has to have wide appeal. That’s why, according to Dasa, there needs to be a “fusion” of architectural styles and techniques to attract “young minds”.

A fight for decentralisation

Cold economics is also part of Prabhupada’s teachings.

In 1972, having amassed a fortune in the US, he wrote a rather instructive letter to a follower: 20,000 copies of the Bhagavad Gita needed to be ordered from Macmillan, at $1.25 apiece. Of these, 5,000 copies were to be dispatched immediately to India, which needed a diversity of religious books — just the Gita wouldn’t do.

The letter is meticulous, even specifying which books should be hard-bound and which paperback. Prabhupada wrote his bonds could be used to pay, but the money had to be returned to his trust fund as he worked to negotiate a profit margin.

Decentralisation was also part of his brand building. In the same letter, he also mentioned that he did not “approve of” any plans to centralise ISKCON management.

“Do not centralise anything. Each temple must remain independent and self-sufficient. That was my plan from the very beginning, why are you thinking otherwise? Once before you wanted to do something centralising with your GBC meeting, and if I did not interfere, the whole thing would have been killed,” wrote a firm Prabhupada. At one point, he even called centralisation a “nonsense proposal.”

Dasa takes this principle seriously, both as spiritual doctrine and management model.

While the Juhu-based Mumbai society was registered in 1966, when Prabhupada was still alive, the Bangalore chapter was registered separately in 1978. Dasa started his version of the ‘movement’ from a rented two-bedroom apartment in the city.

The movement itself has long been hydra-headed, with temples popping up without any ‘official’ sanction, according to him. And so, the question of supremacy should never have come up.

They were always ready to attack and spin a story. We had to counter those narratives

-Chanchalapathi Dasa, senior vice-president of ISKCON Bangalore

“We act as independently as Mumbai. For the sake of accounts and income tax, we were sending funds there. That’s the only difference. Otherwise, all centres are self-sufficient,” he said. “It’s not like one centre can control the funds of another.”

ISKCON Mumbai, however, has always referred to the Bangalore outfit as a branch.

What unites these disparate entities isn’t just Krishna-worship but that they are overseen by the Governing Body Commission, made up of senior ISKCON members from around the world.

“The main function of the Governing Body Commission is to ensure that Prabhupad’s teachings are being followed in all centres, if they are to use the ISKCON brand,” said Dasa. “They protected the brand. There are standards for deity worship, and accountability for the money that we collect. They’re like watch dogs.”

But after Prabhupada’s death in 1977, things went awry. Gurus and temple managers had supposedly gone rogue, and were no longer faithful to the Krishna consciousness. The four ‘sins’ — gambling, “illicit sex”, meat-eating, intoxication — were no longer off-limits. The new-age heads were purportedly dabbling in all.

On top of this, the governance model was changed. The ritvik system, where head priests were merely Prabhupada’s representatives, was abolished. Now, they were all elevated to guru and acharya status. Part of Dasa’s legal fight has been to reinstate the ritvik system.

“A large part of this was done by Madhu Pandit Dasa. He’d be with lawyers, presenting arguments,” said Chanchalapti Dasa.

Through it all, Dasa said he was waging an internal revolution. His challenge to the “corrupt guru system” came to a head at the international GBC in 1999, after which he and his followers were suspended.

Also Read: Lodha brothers ‘amicably’ resolve Rs 5,000-crore dispute over family name

Recruiting the next-gen

For Madhu Pandit Dasa, the legal war was just one front. He’s also on a crusade to build a more expansive, independent future for ISKCON. That vision is rooted not just in Prabhupada’s teachings, but in Dasa’s own background. An IIT Bombay graduate, he studied alongside future titans like Infosys founder Nandan Nilekani. The experience left an imprint and shows in the kinds of recruits he wants to induct.

The religious entrepreneur’s ideal candidate is no confused meaning-seeker: “You finish your graduation. You work for one year, and then you come join us full-time. That’s our model,” he said.

Outreach is necessary to build the right kind of flock. One of the primary pipelines is FOLK — Friends of Lord Krishna. There are 25 of these “youth centres” peppered around Bengaluru and more are being set up outside the city. Students and young professionals are paired with mentors who help them apply Vedic and spiritual lessons to their daily lives.

“Students, employees, IT workers—we invite them to come and listen to our programs as an introduction, so they learn about us,” he said. “God’s grace is required for both spiritual and material growth.”

He added that young people benefit in the realms of both faith and work, which in turn, weds them to the movement.

Dasa is single-minded in his objectives.

“Our goal? To mushroom. We’re going to be across India,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Bunch of idiots vs bunch of idiots.

Who is more idiotic – that’s the essence of this case.